The Effects of Spermidine on Heart Mitochondria in Mice

- This study had an interesting contradiction in its 2D and 3D measurements.

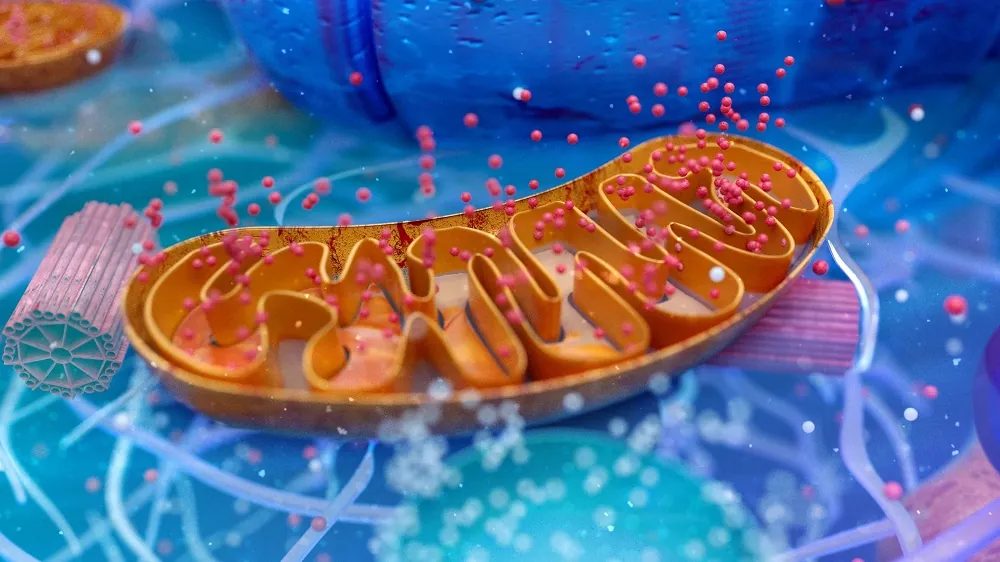

The latest research published in the Journal of Anatomy found that spermidine alters the morphology of mitochondria in aged mouse heart tissue [1].

Mitochondrial dysfunction in the aging heart

Evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction as a driver of aging has been growing in recent years. As we age, our mitochondria produce more reactive oxygen species and take on more DNA damage. Additionally, mitophagy (the cellular consumption of damaged mitochondria) is reduced and the mitochondrial fusion/fission equilibrium is disrupted, with increased fusion occurring in older animals [2-5].

Mitochondrial dysfunction may be particularly impactful in the heart, where energy demands and the number of mitochondria are much greater than in other tissues. The aging heart is central to cardiovascular disease, one of the biggest killers worldwide.

Some treatments have already been found in preclinical studies to target mitochondrial dysfunction. Spermidine treatment has previously demonstrated cardio-protective benefits, increased lifespan, and an ability to induce mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis [4-5].

This connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiovascular aging has been well-studied by longevity researchers, but very little focus has been placed on the morphology of mitochondria. Researchers at the Hannover Medical School in Germany utilized advanced imaging techniques to analyze mitochondria in the hearts of young, aged, and spermidine-treated aged mice.

Does spermidine improve mitochondrial health?

In this study, 18-month-old mice received spermidine treatment in their drinking water for 6 months, after which they were euthanized for tissue analysis. Young (4-month-old) and aged (24-month-old) mice were used as untreated control groups, with each group containing 10 mice.

Anatomically, aged mice had enlarged left ventricles and enlarged cardiomyocytes (heart cells). Spermidine treatment did not improve either ventricle or cardiomyocyte size in old mice. Aged mice had slightly more mitochondria than young mice, but this difference was not statistically significant. Spermidine-treated aged mice had slightly more mitochondria than untreated aged mice, but this difference also was not statistically significant.

Using focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy, the researchers investigated mitochondrial organization and morphology using one mouse from each group.

In the young mouse, mitochondria were similar in size and shape. They also had a highly organized arrangement. The aged mouse had greater variability in mitochondrial size. The individual mitochondria were also in irregular geometries, and, as a group, they were more disorderly in their arrangement.

Meanwhile, the spermidine-treated aged mouse appeared to be between the untreated aged mouse and the young mouse in each of these categories. Additionally, its mitochondria had a greater maximum size than the other two groups.

Interestingly, the researchers also detected mitochondria in the aged mouse, which, in 2D, appeared to be undergoing mitophagy but were not doing so in the 3D reconstruction. This raises important questions about how mitophagy is measured using 2D imaging modalities.

In summary, the present study confirms that age-associated left ventricular hypertrophy is not accompanied by increased quantity of mitochondria. However, the autophagy inducer spermidine increased the number of mitochondria in the old mice. We propose that the observed changes of mitochondrial arrangement, especially their shape and size variation in old mice are a structural correlate of altered mitochondrial dynamics.

Conclusion

While more research on the morphology of aging mitochondria is needed, this study ultimately leaves much to be desired. Only one mouse was used in each group for the 3D reconstruction portion of the study. Therefore, there is no way to know whether the differences seen between mice were due to age, spermidine treatment, or simply individual variability.

Of course, the study does still provide value to the field. 3D morphological studies of mitochondria are few and far between, and this data provides valuable insight for other researchers to compare their results to. It also could serve as the basis for developing quantitative measurements in the future, which are much preferred to the qualitative measurements made in this study.

Literature

[1] Messerer, J. et al. Spermidine supplementation influences mitochondrial number and morphology in the heart of aged mice. Journal of Anatomy (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13618

[2] Lesnefsky, E.J., Chen, Q. & Hoppel, C.L. Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circulation Research (2016). https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.307505

[3] Wierich, M.C., et al. Cardioprotection by spermidine does not depend on structural characteristics of the myocardial microcirculation in aged mice. Experimental Gerontology (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2019.01.026

[4] Eisenberg, T. et al. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nature Medicine (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4222

[5] Wang, J. et al. Spermidine alleviates cardiac aging by improving mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Aging (Albany NY) (2020). https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102647