In a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a research team led by Carlo Condello presented their results from a study of the sliced brain fragments of deceased Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. It appears different amyloid-beta prions are uniquely associated with different AD variants [1].

A primer on Alzheimer’s disease

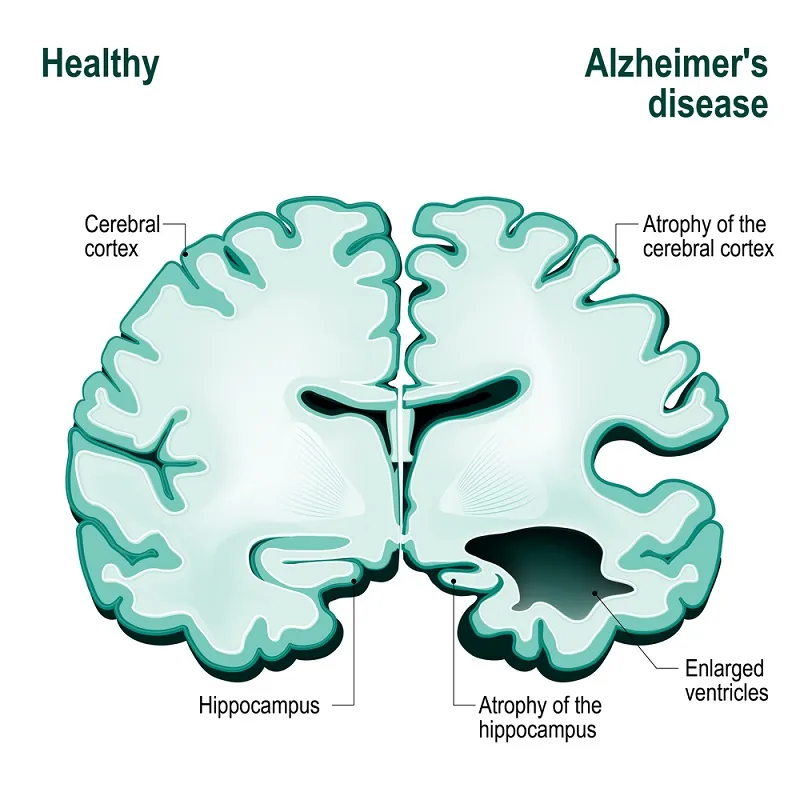

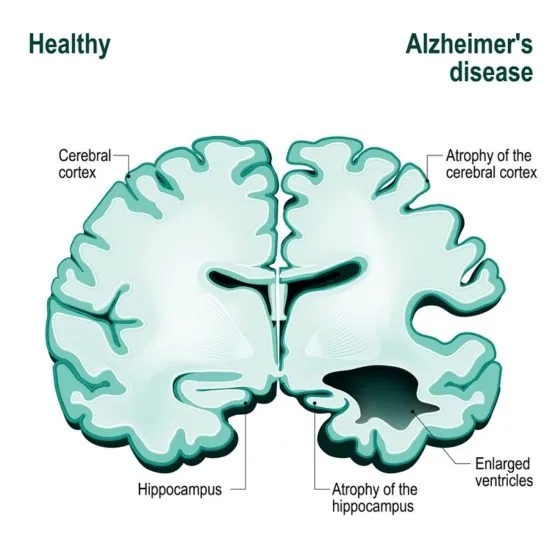

AD is a chronic neurodegenerative disease affecting about 5% of the population above 65 years of age—the time when the first symptoms usually manifest. It is estimated to be the cause of up to 70% of all cases of dementia, which according to WHO projections, by 2050 will be around 115 million.

Initial symptoms may be as apparently inconspicuous as forgetting somebody’s name or being easily confused by unfamiliar situations, but eventually, they become more severe, significantly affecting the patient’s cognitive abilities, impairing speech, inducing immotivated anxiety or aggressive behavior, and even delusions. As the disease progresses, patients become unable to perform fine motor tasks, such as dressing, and to take care of themselves. Eventually, patients become bedridden, incapable of feeding themselves or performing even the simplest tasks. Death usually occurs as a consequence of the complications that eventually arise.

Amyloids and the new study

The exact cause of AD is not clear, but different theories have been proposed, suggesting causes ranging from genetic factors to amyloid-beta and tau protein build-up, to reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, to a combination of different possible factors.

However, it is established that Alzheimer’s patients show an abnormally high presence of amyloid plaques—misfolded protein aggregates that build up in the patients’ brains—and since 1991, the hypothesis that this excess may be the root cause of the disease has been one of the most prevailing. More precisely, it is thought that the real culprit might be amyloid-beta prions—a type of infectious protein, in the sense that they can induce other, normal protein to misfold in their same way and thus spread and cause disease, somewhat resembling a viral infection.

In the study by Condello’s team, slices from the brains of 41 deceased AD patients were examined. Researchers used fluorescent probes—chemicals that bind to specific molecules and, by their own fluorescence, “highlight” them—to locate amyloids and confocal spectral analysis to analyze the samples. They found that each patient affected by a certain, specific AD variant exhibited only one or two different strains of amyloid-beta prions; this seems to indicate that initial, more stable strains may take over other prion strains and become dominant, potentially explaining the different features of the various diseases in within the Alzheimer’s spectrum.

In their paper, the team stresses the urgency of developing clinical PET probes sensitive enough to detect different prion strains in patients’ brains, which may allow not only earlier detection of AD—and thus grant more time for a therapeutic intervention—but also tailoring treatments to each individual case.