A Path Towards Restoring Thymic Function

- This study offers insight into the specific biochemistry of thymic involution.

A study published in Cell Reports shows how the thymus is stimulated to repair itself when dying thymocytes are depleted, paving the way towards novel methods of thymic regeneration.

Cycles of involution, not a steady decline

The researchers cite previous research showing that the thymus, despite being extremely sensitive to insults such as radiation and chemotherapy, is capable of regeneration after injury [1]. Given what we know about thymic involution, the gradual deterioration of the thymus with age, this seems contradictory; why would an organ that is so well-known for deterioration have such self-repair capacities?

The researchers of this study remind us that, rather than a steady decline, the thymus undergoes cycles of involution and repair, and the balance tilts farther and farther towards involution as we age.

How damage stimulates repair

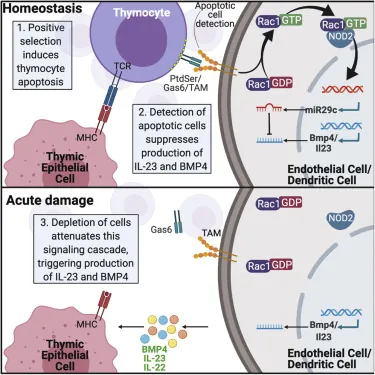

Prior research shows that the natural regeneration of the thymus is driven by two main factors: IL-23, which works through the downstream production of IL-22 [2], along with BMP4 [3]. Each of these factors has been shown to regenerate the thymus [1]. However, the biology of what stimulates and suppresses the natural production of these factors has not previously been thoroughly examined.

This study, intending to bridge that gap, has demonstrated that apoptotic (dying) thymocytes stimulates the NOD pathway, which suppresses these regenerative factors. When acute damage causes the destruction of these thymocytes, this suppression is removed, thus allowing the thymus to regenerate itself.

The researchers created mice that do not produce NOD, and these mice had more thymic activity than mice that do produce it, both before and after injury. Investigating further. the researchers also found that the microRNA miR29c-5p is responsible for mediating this NOD pathway, and they discovered the specific way in which miR29c-5p interferes with BMP4.

Conclusion

This research represents a breakthrough, despite building upon an enormous amount of prior research into the thymus and its workings. As the authors of this paper suggest, it may be possible to develop an intervention that directly interferes with NOD, allowing the thymus to regenerate itself despite the presence of apoptotic thymocytes.

While current methods of thymic regeneration are being investigated in humans, that is a broader, less direct approach than something that directly targets the specific biochemistry involved. If a more direct approach can be found to work in humans without serious side effects, thymic involution as we know it could be considered a treatable ailment, thus restoring a large part of immune function to older people.

Literature

[1] Kinsella, S., & Dudakov, J. A. (2020). When the damage is done: injury and repair in thymus function. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 1745.

[2] Dudakov, J. A., Hanash, A. M., Jenq, R. R., Young, L. F., Ghosh, A., Singer, N. V., … & Van Den Brink, M. R. (2012). Interleukin-22 drives endogenous thymic regeneration in mice. Science, 336(6077), 91-95.

[3] Wertheimer, T., Velardi, E., Tsai, J., Cooper, K., Xiao, S., Kloss, C. C., … & van den Brink, M. R. (2018). Production of BMP4 by endothelial cells is crucial for endogenous thymic regeneration. Science immunology, 3(19).