Age-Related Changes in RNA Transcription Speed

- Going too fast might be leading to mistakes.

Research published yesterday in Nature has described one way in which RNA sequencing changes in the cell with age and how this may be linked to lifespan.

Transcriptional elongation

Transcriptional elongation is a fundamental biological process, as it affects the basic steps involved in the production of RNA, which is responsible for executing the instructions found in DNA [1]. However, like with other biological processes, RNA transcription is affected by aging, and protecting against age-related transcriptional changes has previously been found to extend lifespan in C. elegans worms [2].

Like with many other fundamental biological processes, the effects of aging on RNA transcription are not fully elucidated, and this research offers a new perspective by focusing on a little-known aspect of transcription: speed.

Slower is generally better

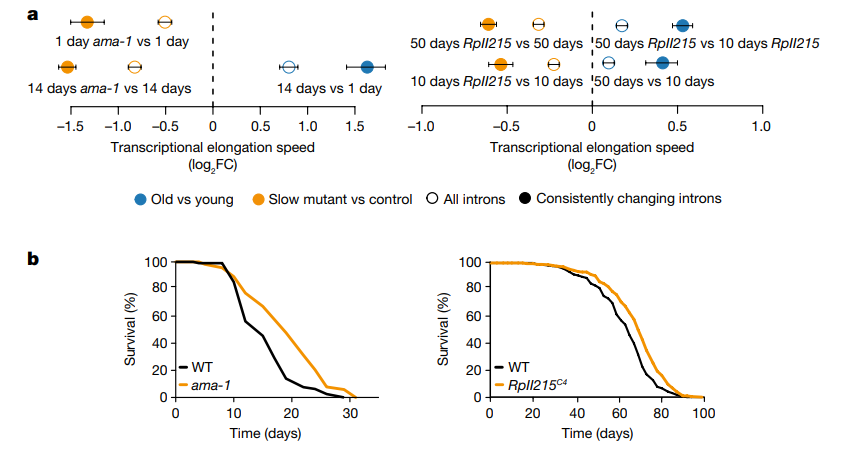

A close examination of finished and unfinished RNA informs researchers of how quickly it is being elongated by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) [3], and when a cell is killed quickly, its unfinished RNA work remains as it was. Modern sequencing analysis techniques let researchers examine a great many cells at once, comparing older cells to their younger counterparts.

In this study, the researchers used cells from a great many organisms and models, including human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), blood from human donors, mouse and rat organs, worms, and flies. In every sample tested, cells driven to senescence and cells taken from older animals were found to have significantly and substantially more rapid transcriptional elongation, on average, than younger cells. The transcription of a few genes was found to slow down with age instead.

Negative changes to RNA were also found with age, although this line of research was generally inconclusive. Rare splices and mismatches did not seem to be consistent across animal models, particularly mammals, which the researchers attribute to their more complex splicing systems.

Testing potential interventions

The researchers tested interventions known to extend lifespan: dietary restriction in rodents and insulin processing in worm and fly models. While RNA 26-month-old (significantly aged) mice did not display any benefit, these researchers found that these lifespan-extending interventions also slow down RNA processing in young and middle-aged mice, as they do all the other models.

Then, the researchers tested causation the other way: does slowing RNA elongation extend lifespan? By introducing specific mutations of Pol II into worm and fly models, the researchers produced evidence that this is the case in these organisms. Although the effects were modest, they were statistically significant. Slowing down Pol II was also found to reduce the number of transcriptional errors in three of four models.

Overexpression of histones, which are associated with the health of nuclei and lifespan in non-mammalian models, was also found to slow down RNA elongation and entry into senescence; however, the researchers also noted here that slowing down elongation too much may also have negative effects.

Conclusion

Much of aging research is based around repeatedly asking the question “What causes that?” and then looking for ways to reverse the root causes that are found in the process. While this research is very preliminary, the authors of this paper may have uncovered clues to one such fundamental origin. Further research must be done to discover if it is truly a good idea to encourage RNA transcription to slow down and take its time more often in mammals.

Literature

[1] Bentley, D. L. (2014). Coupling mRNA processing with transcription in time and space. Nature Reviews Genetics, 15(3), 163-175.

[2] Rangaraju, S., Solis, G. M., Thompson, R. C., Gomez-Amaro, R. L., Kurian, L., Encalada, S. E., … & Petrascheck, M. (2015). Suppression of transcriptional drift extends C. elegans lifespan by postponing the onset of mortality. Elife, 4, e08833.

[3] Ameur, A., Zaghlool, A., Halvardson, J., Wetterbom, A., Gyllensten, U., Cavelier, L., & Feuk, L. (2011). Total RNA sequencing reveals nascent transcription and widespread co-transcriptional splicing in the human brain. Nature structural & molecular biology, 18(12), 1435-1440.