Anti-Inflammatory Diets Mitigate Risk of Dementia

- These results were based on food questionnaires and UK Biobank data.

A new study suggests that an anti-inflammatory diet can significantly reduce the risk of dementia and delay its onset even in people with existing cardiometabolic diseases [1].

Is it too late to lower the risk?

Cardiometabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, heart attack, and stroke, strongly contribute to the risk of developing dementia later in life [2]. It is common wisdom that a healthy diet can help prevent or delay the onset of those diseases [3], but can it mitigate the risk of dementia after those co-morbidities have developed? That was the question that an international group of researchers from the US, Sweden, and China set out to answer in a new study.

The study was based on UK Biobank, a treasure trove of health data on hundreds of thousands of British citizens. The researchers built a sample of more than 80,000 adults over 60 who were dementia-free at baseline and were followed up for periods up to 15 years, with a median period of 12.4 years.

Several times over the course of the follow-up, the participants filled out an elaborate food questionnaire. This allowed the researchers to calculate a dietary inflammation score based on the reported intake of 31 ingredients. Inflammation is known to play a major role both in cardiometabolic diseases and in dementia.

Lower risk, later onset, and larger brains

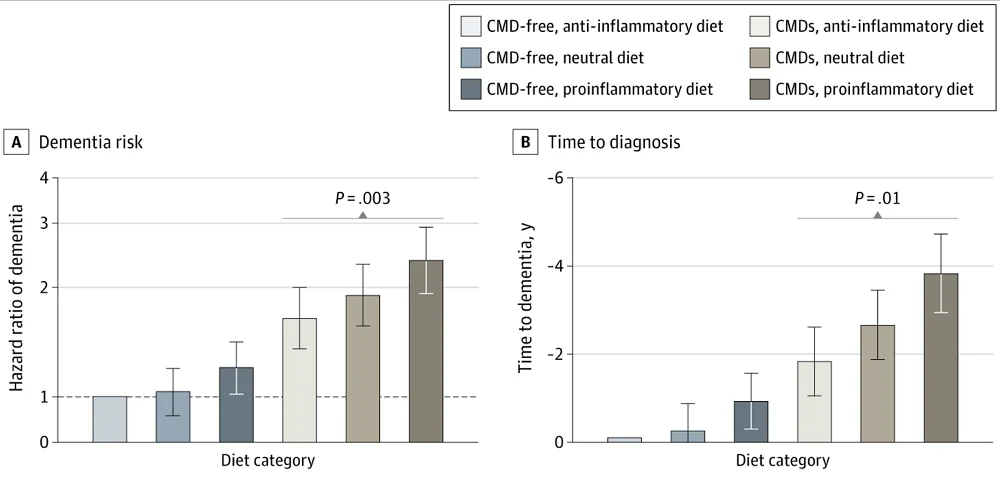

During follow-up, close to 1,600 participants (1.9%) developed dementia. The presence of cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs) was predictably associated with a massive 81% increase in dementia risk. However, an anti-inflammatory diet mitigated this risk significantly: participants with CMDs who consumed an anti-inflammatory diet had a 31% lower risk of dementia compared to similar people who consumed a pro-inflammatory diet. Moreover, a pro-inflammatory diet increased the risk of dementia even in people without CMDs. In people who eventually developed dementia, an anti-inflammatory diet seemed to delay its onset by as much two years.

A subsample of 8,917 participants underwent MRI imaging during follow-up. The study revealed that an anti-inflammatory diet affected not just dementia risk but brain structure itself. In people with CMDs, an anti-inflammatory diet was associated with significantly larger total brain volume, grey matter volume, white matter volume, and white matter hyperintensity volume. The latter is the total volume of regions within the brain’s white matter that appear hyperintense, or brighter, on certain types of MRI scans. These hyperintensities have been linked to cognitive decline, stroke, and other cerebrovascular diseases.

What is an anti-inflammatory diet?

The researchers controlled for several possible confounding variables, including socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, body-mass index, and various health parameters. They also ran several sensitivity analyses, such as excluding people who received a dementia diagnosis during the first five years of follow up and hence could have undiagnosed dementia at baseline.

The anti-inflammatory diets consumed in this study are generally based on fruits and vegetables, whole grains, unsaturated fats, and lean proteins. They emphasize fiber-rich foods, omega-3s, vitamin C, and polyphenols, and minimize saturated and trans fats. The Mediterranean diet is a good example of a low-inflammation diet. However, inflammatory responses to food can be highly individual, depending on factors like genetics, gut microbiota, and immune system sensitivity.

In this cohort study, participants with CMDs and an anti-inflammatory diet had a lower risk of dementia compared with those with a proinflammatory diet. Moreover, people with CMDs and an anti-inflammatory diet had significantly higher GMV and lower WMHV than their counterparts with a proinflammatory diet. Together, these results highlight an anti-inflammatory diet as a modifiable factor that may support brain and cognitive health among people with CMDs.

Literature

[1] Dove, A., Dunk, M. M., Wang, J., Guo, J., Whitmer, R. A., & Xu, W. (2024). Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Dementia in Older Adults With Cardiometabolic Diseases. JAMA Network Open, 7(8), e2427125-e2427125.

[2] Qiu, C., & Fratiglioni, L. (2015). A major role for cardiovascular burden in age-related cognitive decline. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 12(5), 267-277.

[3] Wang, W., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Luo, B., Lin, Z., Chen, K., & Liu, Y. (2023). Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic health: Clinical evidence and mechanism. MedComm, 4(1), e212.