Drug Leads to Drastic Weight Loss With Diet and Exercise

- Tirzepatide affects the feedback mechanisms that inhibit weight loss.

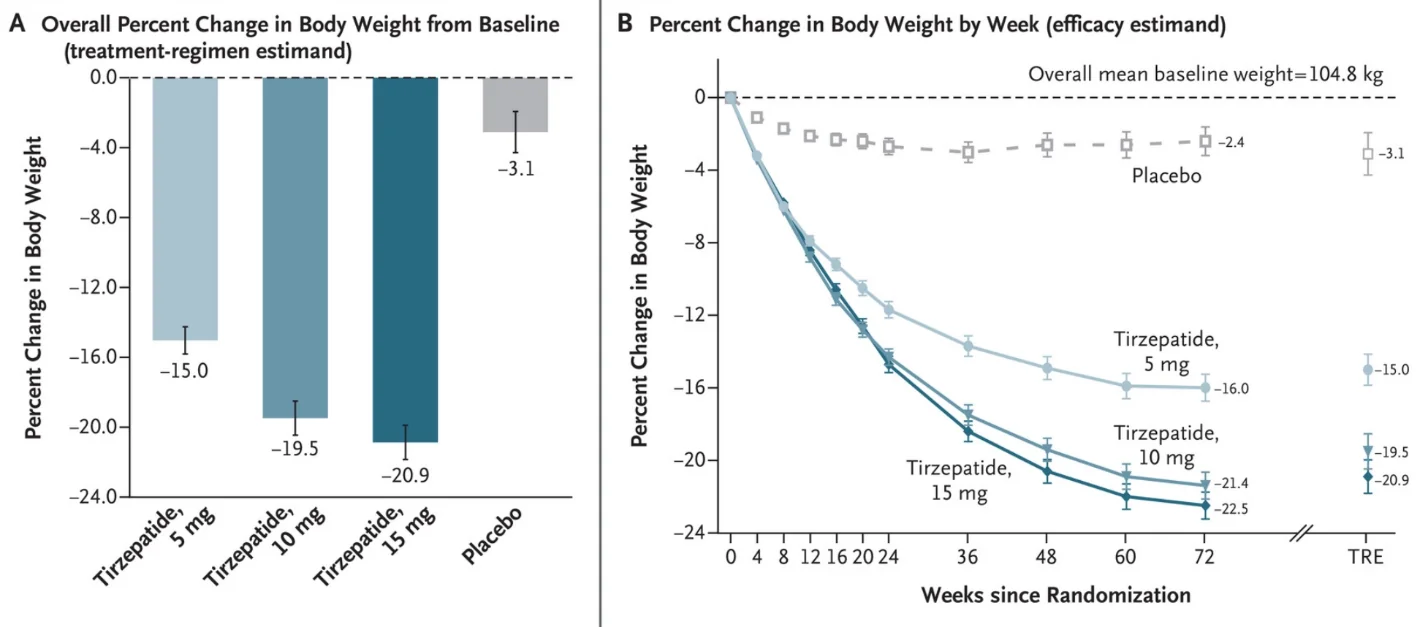

A large Phase 3 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that an existing drug combined with a healthy diet and mild exercise leads to an average weight loss of 20% [1].

Diet and exercise are not always enough

Being a known comorbid factor in many diseases of aging, obesity is tightly linked to both healthspan and lifespan [2]. Other than drastic and potentially harmful interventions, counting calories and engaging in exercise are not always enough to cause weight loss. Evidence has been mounting that diet and exercise prompt counterbalancing biological reactions that make weight reduction and maintenance hard to achieve. In sum, our bodies resist our attempts to lose weight [3].

Medication can enhance the effectiveness of diet and exercise, and scientists continue discovering new candidate drugs in this relatively new field of study. Previous research has highlighted two closely related hormones: GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) and GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide). Both belong to the incretin class of molecules that are released by the body after a meal and boost the secretion of insulin.

GLP-1 receptor agonists have already been approved for the treatment of diabetes and long-term weight management. Interestingly, these drugs also seem to improve cardiovascular function and reduce inflammation, highlighting the importance of glucose homeostasis for overall health. Some other anti-diabetes drugs, most notably metformin and acarbose, are among the leading life-prolonging drug candidates, due to similar organism-wide actions.

Novel combination therapy

The authors of this new study hypothesized that a combination treatment targeting both GLP-1 and GIP pathways could have a synergistic effect on weight loss. Luckily, such a medication, tirzepatide, already exists and was approved just last month to treat diabetes.

Eli Lilly sponsored this large-scale, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, which was run simultaneously at 119 sites in nine countries. 2539 adults participated in the trial, almost all of them with BMIs of greater than 30, the clinical threshold for obesity. The mean weight of the participants was 104.8 kg, and the mean age was 45.

The participants were divided into four equally sized groups: the placebo group and the 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg study groups. Diabetes, bariatric surgery, and other weight-reducing medications were some of the reasons for exclusion. Importantly, all the participants were also subjected to lifestyle interventions that included diet and lifestyle counseling, a deficit of 500 calories per day, and at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week. The treatment duration was 72 weeks, and the drug was administered weekly.

Surgery-like results

Despite doing all the right things, the placebo group saw only mild average weight loss that quickly plateaued at 3.1% of body mass. While a small number of placebo patients did achieve substantial weight reduction, many more failed, showing just how hard it is to shed pounds. The outcomes in the study groups were quite different: the average weight loss was 15% in the 5 mg group, 19.5% in the 10 mg group, and 20.9% in the 15 mg group. The 10 mg and 15 mg groups closely resembled each other in most other metrics as well.

Highlighting the impressive impact of the treatment, a full 56.7% of participants in the 15 mg group achieved at least 20% weight reduction, compared to just above 3% in the placebo group. 96.3% in the 15 mg group and only 27.9% in the placebo group achieved their personalized weight loss targets. Contrary to the placebo group, weight loss in the high-dose groups continued throughout the treatment period, slowing but not plateauing.

The treatment also brought benefits in waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting insulin level, and lipid levels. 95.3% of the participants with pre-diabetes at baseline regained normal glucose levels. Interestingly, this also happened to 61.9% of pre-diabetic participants in the placebo group, showing that healthy diet and mild exercise can affect glucose levels even when not accompanied by weight loss.

Overall, only a fraction of participants suffered from serious adverse effects. The effects that were significantly more prevalent in the study groups vs the placebo group included nausea, diarrhea, constipation, and vomiting, and were mostly observed during the initial stage of the study when the participants were getting used to their dose. Overall, the treatment was deemed safe at all doses.

To put these results into perspective, currently approved anti-obesity medications yield only about 3-8% weight reduction on average. Bariatric surgery can cause a 25-30% weight loss over a 1–2-year period, but it is highly invasive and carries long-term risks.

Conclusion

This is a highly robust Phase 3 study that repurposes an already approved anti-diabetes medication for weight loss, which means that the road to clinical use should be short. The study’s spectacular results show yet again that lifestyle changes are usually not enough to overcome obesity, but science can help. Still, healthy diet and exercise are highly beneficial even without weight loss.

Literature

[1] Jastreboff, A. M., Aronne, L. J., Ahmad, N. N., Wharton, S., Connery, L., Alves, B., … & Stefanski, A. (2022). Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine.

[2] Kitahara, C. M., Flint, A. J., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Bernstein, L., Brotzman, M., MacInnis, R. J., … & Hartge, P. (2014). Association between class III obesity (BMI of 40–59 kg/m2) and mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. PLoS medicine, 11(7), e1001673.

[3] Aronne, L. J., Hall, K. D., M. Jakicic, J., Leibel, R. L., Lowe, M. R., Rosenbaum, M., & Klein, S. (2021). Describing the weight‐reduced state: Physiology, behavior, and interventions. Obesity, 29, S9-S24.