Late-Life Treatment Extends Nematode Lifespan by Two-Fold

- This approach targets their version of the insulin pathway.

Scientists have managed to extend the lifespan of C. elegans nematode worms by as much as 135% by blocking an insulin-related pathway very late in life [1].

The long-lived mutants

Back in the late 80s and early 90s, experiments with C. elegans, tiny nematode worms, became one of geroscience’s first major successes. Scientists showed that if you knock out a single gene, Daf-2, the worms live up to two times longer [2]. This is not particularly impressive, as C. elegans’ average lifespan is just a couple of weeks. On the other hand, this is what makes C. elegans a popular model organism for studying aging.

The Daf-2 gene belongs to the insulin receptor family. Mammals do not have a single gene that is similar to Daf-2. Instead, Daf-2 corresponds to several pathways in humans, most notably to the insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) pathway. Obviously, the two-fold increase in lifespan could not be reproduced in humans, though experiments with blocking IGF-1 via antibodies in mice led to a modest improvement in lifespan and healthspan [3].

Yet, for worms, this longevity comes with a price tag. The modified nematodes develop numerous adverse phenotypes, including decreased fertility, a small body size, and a propensity to enter the so-called “dauer state”, which is similar to hibernation for worms.

Scientists have been trying to work their way around those problems for quite some time. For instance, there were attempts to regulate DAF-2 levels by RNA interference. Although this mostly prevented the development of the unwanted phenotypes, the increase in lifespan was much more modest compared to a Daf-2 knockout, possibly due to the fact that RNAi machinery weakens with age.

Knockout on demand

In this new study, the scientists tried a different approach: instead of a full Daf-2 gene knockout, they created a mechanism that degrades the DAF-2 protein on demand when another protein is introduced.

Using CRISPR, the scientists inserted a new sequence into Daf-2 that added a degron, a part of a protein that promotes its degradation. The degron though could only be triggered by another protein called auxin. Without auxin in the system, the worms would have normal DAF-2 levels. The researchers performed a series of experiments to determine that the hefty 68-amino acid-long degron addition did not interfere with the functions of the DAF-2 protein.

When auxin was introduced, the resulting DAF-2 degradation led to a maximum of a 40% decrease in the protein’s levels rather than to its complete loss. Despite that, when started early in life, the treatment still caused the development of the phenotypes that usually accompany Daf-2 deletion.

A second life for old worms

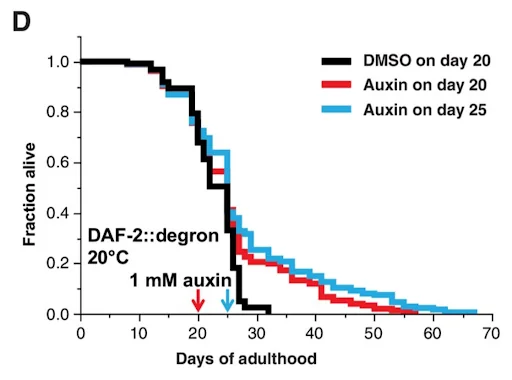

The breakthrough came when the scientists attempted to start the intervention very late in life, which, for nematodes, is between days 20 and 25; by this time, three-quarters of the worms have already died of old age. The remaining quarter, after receiving auxin that had triggered DAF-2 degradation, continued to live for up to 67 days in total. This corresponds to a 70% to 135% increase in lifespan. The researchers claim that these results surpass even the famous longevity of Daf-2 mutants.

This effect was stronger when auxin was applied on day 25 rather than 20. This might seem counterintuitive, but it is not: the passage of time weeded out less aging-resistant worms. Those that remained were naturally more long-lived, which is probably why the longevity boost they received was more pronounced.

Image: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is a solvent widely used as a negative control for lifespan assays in C. elegans. Interestingly, DMSO itself has recently been shown to mildly extend C. elegans lifespan [4], which means that the longevity-promoting effect of auxin-dependent DAF-2 degradation might be even greater than it seems.

Conclusion

Decades ago, the original experiments with Daf-2 deletion sparked enthusiasm in the longevity community by showing that extreme life extension is possible, at least in simple organisms. This new study provides yet another reason for cautious optimism: it joins the growing cohort of studies demonstrating that late-life interventions can still lead to a major increase in lifespan. This could be especially important in the context of pathways such as insulin/IGF-1, which are essential for healthy development of an organism and should not be targeted earlier in life. The idea of trying life-extending interventions on geriatric animals has been gaining steam lately, and we will continue to cover any new developments.

Literature

[1] Venz, R., Pekec, T., Katic, I., Ciosk, R. & Ewald, C. Y. (2021). End-of-life targeted degradation of DAF-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor promotes longevity free from growth-related pathologies. eLife 10, e71335.

[2] Mao, K., Quipildor, G. F., Tabrizian, T., Novaj, A., Guan, F., Walters, R. O., … & Huffman, D. M. (2018). Late-life targeting of the IGF-1 receptor improves healthspan and lifespan in female mice. Nature communications, 9(1), 1-12.

[3] Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A., & Tabtiang, R. (1993). A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature, 366(6454), 461-464.

[4] Frankowski, H., Alavez, S., Spilman, P., Mark, K. A., Nelson, J. D., Mollahan, P., … & Ellerby, H. M. (2013). Dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl formamide increase lifespan of C. elegans in liquid. Mechanisms of ageing and development, 134(3-4), 69-78.