Promoting Health and Longevity Through Diet

- Quality and quantity of food can impact many aspects of health and longevity.

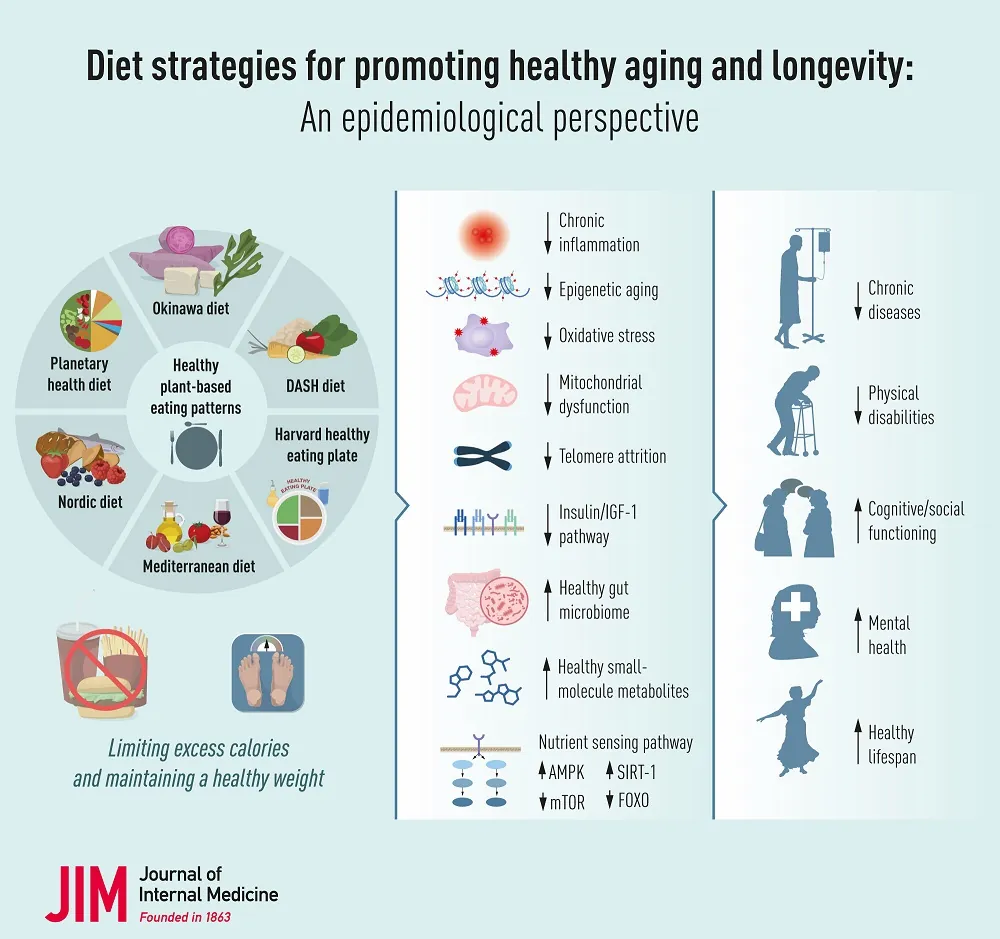

A review published in the Journal of Internal Medicine summarized current knowledge on the impact of dietary factors on chronic diseases and longevity [1].

Restrict calories, live healthier and longer

The choice of what someone eats obviously has a profound impact on that person’s health, but the amount is also important. Caloric restriction, the practice of reducing caloric intake without causing malnutrition, has been shown in many laboratory organisms to increase lifespan and delay the onset of age-related diseases [2]. However, studying caloric restriction in humans is challenging.

In the longest caloric restriction trial, non-obese participants achieved 12% calorie reduction over 2 years. Researchers observed improvements in several biomarkers: blood lipids, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and pro-inflammatory cytokines [3]. However, due to the short duration of the study and the small sample, long-term chronic disease and mortality risk cannot be reliably assessed.

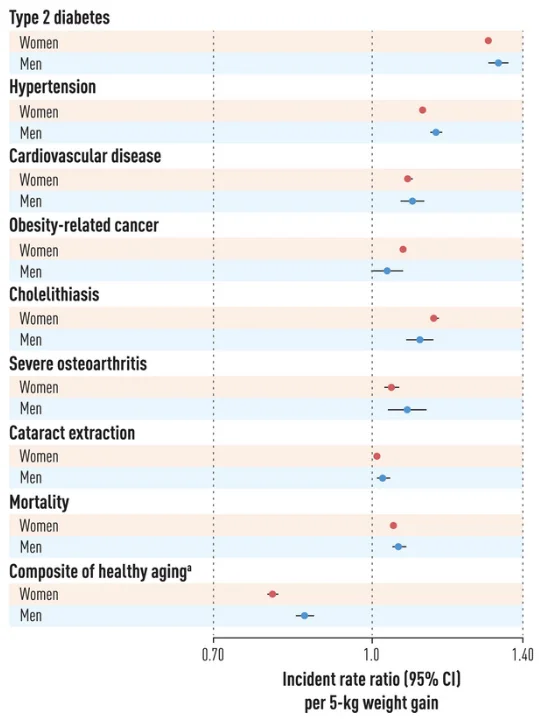

Studies assessing body weight and shape trajectories are used as a marker and substitute for detailed calorie intakes. Such studies show the health benefits of maintaining a stable-lean body shape, which include decreased risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [4, 5, 6]. Results also show an association between an elevated risk of several diseases and weight gain, even in 5 kg (11 lb) increments, during young and middle adulthood [6].

Quality and quantity of fats, protein, and carbs matters

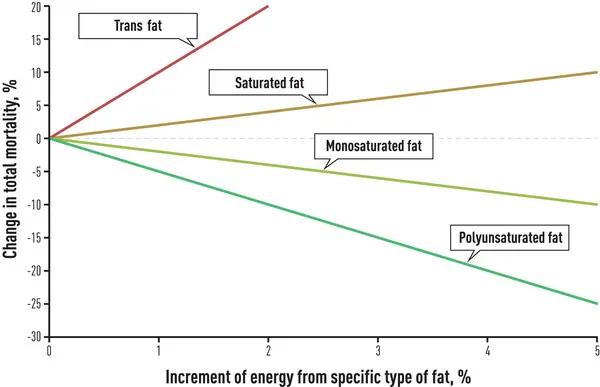

Research spanning several decades provides a wealth of evidence supporting the idea that different types of fat are linked to different effects on health. Some studies have associated higher intake of unsaturated fats with lower mortality rates [7]. On the other hand, consumption of trans fats and saturated fats has been documented to have the opposite effect, and it is associated with increased mortality.

The food source of fat is also important, with plant sources, but not animal sources, lowering the risk of coronary artery disease [8]. Protein restriction, specifically restricting particular amino acids, such as methionine and tryptophan, extends the lifespan of laboratory model organisms [9, 10].

In humans, associations between protein intake and mortality are still being researched. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) demonstrates that, for individuals between 50-65 years old, high animal protein, but not high plant protein, was associated with a 75% increase in overall mortality during 18 years of follow-up. However, for individuals over 65, higher protein intake was associated with lower mortality [11].

This hasn’t been observed in other cohort studies, where age was not a modifying factor. In those studies, higher animal protein intake was associated with cardiovascular mortality, and higher plant protein intake was inversely associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [12].

Carbohydrate intake is also intensely studied. Animal studies on low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets suggest that they can enhance longevity and healthspan [13]. Short-term randomized clinical trials show that restricting the consumption of carbohydrates can improve several biomarkers, such as by lowering blood glucose or improving insulin sensitivity [14].

However, adherence to a low-carb diet is challenging and can result in inadequate intake of fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

Current research suggests that the health impact of a low-carb diet depends on the type of fat and protein consumed [15]. An animal-based low-carb diet is associated with higher mortality. In comparison, a low-carb diet in which vegetables are mostly the sources of protein and fat is associated with lower mortality, especially mortality caused by cardiovascular diseases. Generally, studies agree that carbohydrate quality, more than quantity, plays a more important role in the development of chronic disease.

Polyphenol-rich plant foods

Polyphenols are a group of natural compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic properties. They are found in many plant-based foods. Consumption of polyphenols is linked to cardiometabolic benefits, improved cognitive function, decreased neurodegenerative disease risk [16], and maintenance of healthy gut microbiota [17]. Some research has found that polyphenols have aging properties, and they influence many hallmarks of aging [18].

Bringing it all together into a healthy diet

The authors rightly notice that various healthy dietary components are not consumed in isolation but must be combined into a healthy dietary pattern. One of the diets, which is regarded as healthy, is the Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet is abundant in plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, and olive oil.

Current research points out that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced risks of many conditions and diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, heart failure, neurodegenerative diseases, and mortality [19].

The Nordic diet has some similarities to the Mediterranean diet. It focuses on plant-based and locally sourced foods, with a major difference of using mainly rapeseed oil instead of olive oil. Available data, although scarce, suggests that following a Nordic diet lowers the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. However, no long-term studies have been conducted so far [20].

This paper also discusses the Okinawan diet. Okinawa Island is one of the Blue Zones, a place with a high number of centenarians. Diet is one of the components believed to be responsible for the increased lifespan of Okinawa’s residents. It puts “emphasis on root vegetables (mainly purple sweet potatoes), green and yellow vegetables, soybean-based foods, seaweeds and algae, tea, and a variety of medicinal plants (e.g. bitter melon) and spices such as turmeric” with limited meat consumption. Additionally, Okinawans practice Hara Hachi Bu, that is, eating until they are 80% full, which resembles caloric restriction.

The authors also discuss vegetarian diets. Small randomized clinical trials have shown improvements in different biomarkers for participants following a vegetarian diet, e.g., reduced blood pressure, total and LDL cholesterol levels, body weight, and other cardiometabolic risk factors. Additionally, large cohort studies of vegetarians suggest they have a reduced risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and lower rates of cancer than nonvegetarians [21].

It’s not only about food

The study authors conclude that while dietary patterns have a profound impact on health, other lifestyle factors are important to increase healthspan and lifespan.

We defined five low-risk lifestyle factors as fulfilling either: never smoking, maintaining normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), 30+ minutes/day moderate to vigorous physical activity, moderate alcohol intake (no more than one drink per day for women and no more than two for men), and a high-quality diet.

Literature

[1] Hu F. B. (2023). Diet strategies for promoting healthy aging and longevity: An epidemiological perspective. Journal of internal medicine, 10.1111/joim.13728. Advance online publication.

[2] Fontana, L., & Partridge, L. (2015). Promoting health and longevity through diet: from model organisms to humans. Cell, 161(1), 106–118.

[3] Kraus, W. E., Bhapkar, M., Huffman, K. M., Pieper, C. F., Krupa Das, S., Redman, L. M., Villareal, D. T., Rochon, J., Roberts, S. B., Ravussin, E., Holloszy, J. O., Fontana, L., & CALERIE Investigators (2019). 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology, 7(9), 673–683.

[4] Song, M., Hu, F. B., Wu, K., Must, A., Chan, A. T., Willett, W. C., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Trajectory of body shape in early and middle life and all cause and cause specific mortality: results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 353, i2195.

[5] Zheng, Y., Song, M., Manson, J. E., Giovannucci, E. L., & Hu, F. B. (2017). Group-Based Trajectory of Body Shape From Ages 5 to 55 Years and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk in 2 US Cohorts. American journal of epidemiology, 186(11), 1246–1255.

[6] Zheng, Y., Manson, J. E., Yuan, C., Liang, M. H., Grodstein, F., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2017). Associations of Weight Gain From Early to Middle Adulthood With Major Health Outcomes Later in Life. JAMA, 318(3), 255–269.

[7] Marklund, M., Wu, J. H. Y., Imamura, F., Del Gobbo, L. C., Fretts, A., de Goede, J., Shi, P., Tintle, N., Wennberg, M., Aslibekyan, S., Chen, T. A., de Oliveira Otto, M. C., Hirakawa, Y., Eriksen, H. H., Kröger, J., Laguzzi, F., Lankinen, M., Murphy, R. A., Prem, K., Samieri, C., … Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Fatty Acids and Outcomes Research Consortium (FORCE) (2019). Biomarkers of Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Circulation, 139(21), 2422–2436.

[8] Zong, G., Li, Y., Sampson, L., Dougherty, L. W., Willett, W. C., Wanders, A. J., Alssema, M., Zock, P. L., Hu, F. B., & Sun, Q. (2018). Monounsaturated fats from plant and animal sources in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among US men and women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 107(3), 445–453.

[9] Solon-Biet, S. M., McMahon, A. C., Ballard, J. W., Ruohonen, K., Wu, L. E., Cogger, V. C., Warren, A., Huang, X., Pichaud, N., Melvin, R. G., Gokarn, R., Khalil, M., Turner, N., Cooney, G. J., Sinclair, D. A., Raubenheimer, D., Le Couteur, D. G., & Simpson, S. J. (2014). The ratio of macronutrients, not caloric intake, dictates cardiometabolic health, aging, and longevity in ad libitum-fed mice. Cell metabolism, 19(3), 418–430.

[10] Miller, R. A., Buehner, G., Chang, Y., Harper, J. M., Sigler, R., & Smith-Wheelock, M. (2005). Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance. Aging cell, 4(3), 119–125.

[11] Levine, M. E., Suarez, J. A., Brandhorst, S., Balasubramanian, P., Cheng, C. W., Madia, F., Fontana, L., Mirisola, M. G., Guevara-Aguirre, J., Wan, J., Passarino, G., Kennedy, B. K., Wei, M., Cohen, P., Crimmins, E. M., & Longo, V. D. (2014). Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population. Cell metabolism, 19(3), 407–417.

[12] Song, M., Fung, T. T., Hu, F. B., Willett, W. C., Longo, V. D., Chan, A. T., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA internal medicine, 176(10), 1453–1463.

[13] Roberts, M. N., Wallace, M. A., Tomilov, A. A., Zhou, Z., Marcotte, G. R., Tran, D., Perez, G., Gutierrez-Casado, E., Koike, S., Knotts, T. A., Imai, D. M., Griffey, S. M., Kim, K., Hagopian, K., McMackin, M. Z., Haj, F. G., Baar, K., Cortopassi, G. A., Ramsey, J. J., & Lopez-Dominguez, J. A. (2017). A Ketogenic Diet Extends Longevity and Healthspan in Adult Mice. Cell metabolism, 26(3), 539–546.e5.

[14] Ludwig, D. S., Hu, F. B., Tappy, L., & Brand-Miller, J. (2018). Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 361, k2340.

[15] Fung, T. T., van Dam, R. M., Hankinson, S. E., Stampfer, M., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2010). Low-carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: two cohort studies. Annals of internal medicine, 153(5), 289–298.

[16] Ammar, A., Trabelsi, K., Boukhris, O., Bouaziz, B., Müller, P., M Glenn, J., Bott, N. T., Müller, N., Chtourou, H., Driss, T., & Hökelmann, A. (2020). Effects of Polyphenol-Rich Interventions on Cognition and Brain Health in Healthy Young and Middle-Aged Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(5), 1598.

[17] Rana, A., Samtiya, M., Dhewa, T., Mishra, V., & Aluko, R. E. (2022). Health benefits of polyphenols: A concise review. Journal of food biochemistry, 46(10), e14264.

[18] Leri, M., Scuto, M., Ontario, M. L., Calabrese, V., Calabrese, E. J., Bucciantini, M., & Stefani, M. (2020). Healthy Effects of Plant Polyphenols: Molecular Mechanisms. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(4), 1250.

[19] Guasch-Ferré, M., & Willett, W. C. (2021). The Mediterranean diet and health: a comprehensive overview. Journal of internal medicine, 290(3), 549–566.

[20] Massara, P., Zurbau, A., Glenn, A. J., Chiavaroli, L., Khan, T. A., Viguiliouk, E., Mejia, S. B., Comelli, E. M., Chen, V., Schwab, U., Risérus, U., Uusitupa, M., Aas, A. M., Hermansen, K., Thorsdottir, I., Rahelic, D., Kahleová, H., Salas-Salvadó, J., Kendall, C. W. C., & Sievenpiper, J. L. (2022). Nordic dietary patterns and cardiometabolic outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomised controlled trials. Diabetologia, 65(12), 2011–2031.

[21] Wang, T., Masedunskas, A., Willett, W. C., & Fontana, L. (2023). Vegetarian and vegan diets: benefits and drawbacks. European heart journal, 44(36), 3423–3439.