Reduced Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Is a New NAD+ Precursor

- Study suggests that this compound has advantages over NMN and NR.

There has been a lot of attention given to the NAD precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR), sold as dietary supplements, to restore nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) levels. However, a new study suggests that there could be a new game in town with the arrival of reduced nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMNH).

Introducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a key coenzyme found in all living cells. It is a dinucleotide, which means that it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an adenine base, and the other contains nicotinamide. It appears in two forms in the body: NAD, and, in its reduced state, NADH.

NAD is essential for life, as it is one of the most versatile molecules in the body and an important area of focus for aging research. In the body, it supports DNA repair, activates sirtuins that are known as the longevity genes, facilitates processes such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle (TCA/Krebs cycle), takes part in redox reactions, and allows the electron transport chain inside the mitochondria to function. The downstream activity of NAD supports hundreds of enzymatic reactions and regulates many key processes in cells.

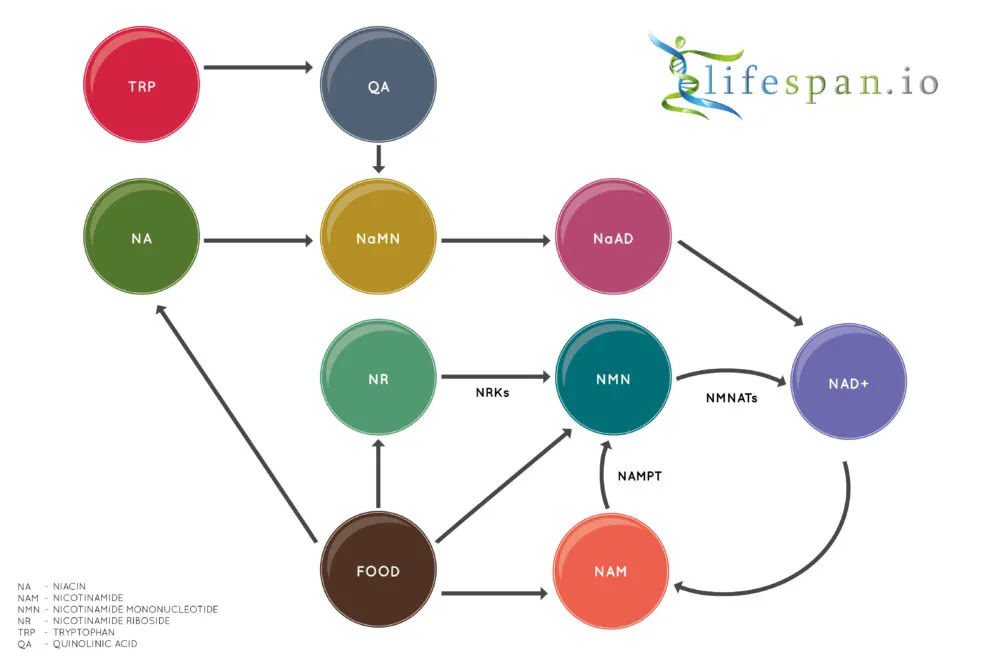

As NAD is critically important, humans have evolved to synthesize it through three main pathways:

First is the Preiss‐Handler pathway, in which the precursor nicotinic acid (NA) in food is converted into NAD through a three-part enzymatic process facilitated by nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT).

Second is the de novo pathway, in which niacin molecules are created from scratch by our own bodies using the essential amino acid L-tryptophan (TRP). The de novo pathway intersects with the Preiss‐Handler pathway, and both go on to become NAD.

Finally, the salvage pathway converts nicotinamide (NAM), also known as niacinamide, into NAD. This pathway has nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) as an intermediate, and nicotinamide riboside (NR) also uses the same salvage pathway. Regardless of pathway, all NAD ends up here, being recycled over and over until other processes cause it to be lost.

Restoring nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide to combat aging

Given the critical role that NAD plays in the activity of enzymes, cellular functions, and metabolism, it is probably no surprise that any decline of NAD leads to metabolic disturbances and sets the stage for various age-related diseases. Multiple studies suggest that as we age, our levels of NAD declines significantly, and for that reason, the restoration of NAD levels has been the focus of significant research efforts in the last few years.

The two popular precursors NMN and NR, marketed as dietary supplements, have been the King and Queen of the NAD scene for quite some time now, but both are not without their issues. NMN and NR both have limitations, such as their maximal NAD boosting effects, which are around 2-fold and hence require higher and considerably more costly doses.

NR has also been shown to increase NAD levels in human blood, but it fails to increase NAD levels in tissues such as muscle despite very high doses, which the researchers discuss in this paper. The researchers suggest that NR’s inefficacy in raising NAD might explain why NR has no apparent effect on total energy expenditure, blood glucose, or insulin sensitivity in humans [1].

NMNH seems to increase nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide more effectively

The new study suggests that reduced nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMNH) is a potent NAD precursor molecule, according to the results seen in both mice and human cells. The researchers developed a method for creating and purifying NMNH at scale and explored the role of the molecule in NAD biology.

Their results demonstrate that NMNH is efficiently processed into NAD in cells. Perhaps most interestingly, the path to achieving this does not involve nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK) or nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which other precursors require in order to become NAD.

During the study, they also showed that the administration of NMNH can also protect renal proximal tubular epithelial cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation‐induced injury.

Lastly, and most importantly, the data also shows that NMNH treatment in mice is able to raise NAD levels in their blood but also in multiple tissues, including the kidneys, and to a higher level than NMN at a similar concentration.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) homeostasis is constantly compromised due to degradation by NAD‐dependent enzymes. NAD replenishment by supplementation with the NAD precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR) can alleviate this imbalance. However, NMN and NR are limited by their mild effect on the cellular NAD pool and the need of high doses. Here, we report a synthesis method of a reduced form of NMN (NMNH), and identify this molecule as a new NAD precursor for the first time. We show that NMNH increases NAD levels to a much higher extent and faster than NMN or NR, and that it is metabolized through a different, NRK and NAMPT‐independent, pathway. We also demonstrate that NMNH reduces damage and accelerates repair in renal tubular epithelial cells upon hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Finally, we find that NMNH administration in mice causes a rapid and sustained NAD surge in whole blood, which is accompanied by increased NAD levels in liver, kidney, muscle, brain, brown adipose tissue, and heart, but not in white adipose tissue. Together, our data highlight NMNH as a new NAD precursor with therapeutic potential for acute kidney injury, confirm the existence of a novel pathway for the recycling of reduced NAD precursors and establish NMNH as a member of the new family of reduced NAD precursors.

Conclusion

These results suggest that reduced NMNH may prove to be a contender for the NAD boosting crown. Hopefully, the researchers’ focus on production at scale, and the lower dosage being needed, mean that NMNH can be created and made available at a far lower price point than the precursors currently available (not including cheap niacin), which carry a hefty price tag due to costly manufacturing requirements.

Literature

[1] Dollerup, O. L., Christensen, B., Svart, M., Schmidt, M. S., Sulek, K., Ringgaard, S., … & Jessen, N. (2018). A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: safety, insulin-sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 108(2), 343-353.