A new study has seen researchers alter the balance of harmful bacteria in the gut microbiome to reduce cholesterol and reverse atherosclerosis in mice fed a high-fat Western diet.

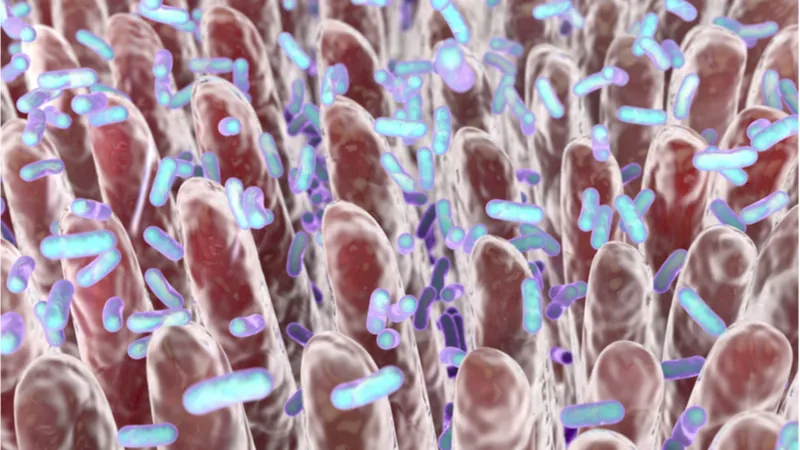

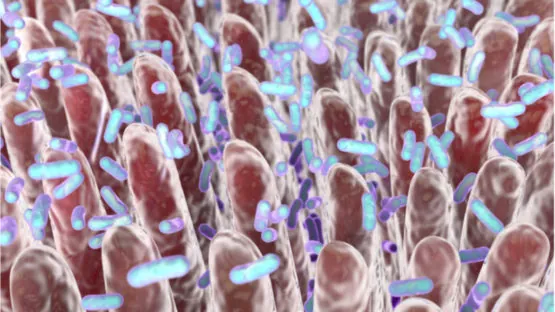

What is the gut microbiome?

The gut microbiome describes the varied community of bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and viruses that inhabit our gut. The four bacterial phyla of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria comprise 98% of the intestinal microbiome.

The microbiome is a complex ecosystem that regulates various aspects of gut function along with the immune system, the nutrient supply, and metabolism. It also helps to control the growth of pathogenic bacteria, protects from invasive microorganisms, and maintains the intestinal barrier. Essentially, the microbiome exists in a delicate balance, and if that balance is disturbed, it can lead to a decline of health and the development of disease.

As we age, the composition and diversity of the microbiome changes, as the beneficial bacteria populations tend to decline and populations of harmful bacteria typically increase in numbers. One emerging hypothesis is that these changes to the gut microbiome lead to detrimental changes elsewhere in the body and could potentially be the origin point of inflammaging, the chronic low-grade smoldering background of inflammation typically observed in older people.

Resetting the microbiome with cyclic peptides

A new study published by researchers at Scripps in the journal Nature Biotechnology has shown how the gut microbiome of mice can be reset to a healthier state using molecules that they have developed [1]. Perhaps the most exciting of all, resetting the microbiome significantly slowed down the progression of atherosclerosis in the treated animals.

The researchers used molecules known as peptides to slow down the growth of harmful gut bacteria, which usually increase in numbers during aging. The mice were given a high-fat diet to develop high cholesterol and accelerate the onset of atherosclerosis. Treatment with the peptides shifted the balance of bacteria in the gut microbiome, which reduced cholesterol levels and greatly slowed down the accumulation of fatty deposits in the arterial plaques that are typical in atherosclerosis.

Normally, our cells regulate the microbiome and keep harmful bacteria under control and helpful bacteria healthy by using a varied collection of secreted molecules, including antimicrobial peptides to keep things in check.

The researchers of this study used cyclic peptides, which are polypeptide chains which contain a circular sequence of bonds. These naturally occurring peptides are generally antimicrobial, and they have a variety of medical applications, including as antibiotics and immunosuppressants. To see if they could find ways to beneficially remodel the microbiome, the researchers screened a library of cyclic peptides.

Using a mouse strain that is genetically vulnerable to high cholesterol levels, they gave them a Western diet, which caused detrimental changes to the microbiome and rapidly elevated blood cholesterol levels while hastening the onset of atherosclerosis. They then sampled the microbiomes of the mice and treated each sample with a different cyclic peptide that had passed the screening process. A day following this treatment, the research team sequenced the bacterial DNA present in the samples to see which peptide, if any, had spurred a beneficial change in the microbiome.

As luck would have it, they identified two peptides that appeared to slow the growth of harmful gut bacteria in the samples. The resulting changes shifted the microbiome balance and diversity back to what is seen in mice that eat a healthy diet.

When they used these peptides on the mice fed a high-fat Western diet, they discovered, after two weeks of treatment, an impressive ~36% reduction of cholesterol compared to the untreated control mice. After a period of ten weeks, the mice had around a 40% size reduction of atherosclerotic plaques in their arteries compared to the control group.

According to the researchers, the successful cyclic peptides had interfered with the outer membranes of the bacteria to slow or even halt their growth. The research team has a catalogue of these peptides, which they have been developing over the course of several years, and claim that the ones they have are harmless to mammalian cells and only interact with bacteria.

Another plus on the safety side is that the cyclic peptides pass through the gut but do not enter the bloodstream and can be taken orally; for example, the mice in this study were given the peptides via their drinking water, meaning that administration is simple and safe. The next step for the researchers is to test their cyclic peptides on mouse models of type 2 diabetes to see if this metabolic condition, which is associated with the microbiome, can be addressed.

The gut microbiome is a malleable microbial community that can remodel in response to various factors, including diet, and contribute to the development of several chronic diseases, including atherosclerosis. We devised an in vitro screening protocol of the mouse gut microbiome to discover molecules that can selectively modify bacterial growth. This approach was used to identify cyclic d,l-α-peptides that remodeled the Western diet (WD) gut microbiome toward the low-fat-diet microbiome state.

Daily oral administration of the peptides in WD-fed LDLr-/- mice reduced plasma total cholesterol levels and atherosclerotic plaques. Depletion of the microbiome with antibiotics abrogated these effects. Peptide treatment reprogrammed the microbiome transcriptome, suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-1β), rebalanced levels of short-chain fatty acids and bile acids, improved gut barrier integrity and increased intestinal T regulatory cells. Directed chemical manipulation provides an additional tool for deciphering the chemical biology of the gut microbiome and might advance microbiome-targeted therapeutics.

Conclusion

There is a growing appreciation for the role of the gut microbiome in health and aging and the development of therapies that acknowledge that we are symbiotic organisms that rely on the health of our resident bacteria. Our microbiome has the potential to keep us healthy or harm us, depending on the delicate balance within, and understanding this and being able to manipulate it to promote health could pay big dividends in the near future.

Literature

[1] Chen, P. B., Black, A. S., Sobel, A. L., Zhao, Y., Mukherjee, P., Molparia, B., … & Pinto, A. F. (2020). Directed remodeling of the mouse gut microbiome inhibits the development of atherosclerosis. Nature Biotechnology, 1-10.