Sauna Combined with Exercise Improves Cardiovascular Health

- Blood pressure, oxygen use, and cholesterol were all affected.

In a randomized, controlled trial, scientists have shown that sauna and exercise, when taken together, might have a synergistic, beneficial effect on cardiovascular health and cholesterol levels [1].

Turn up the heat

Sauna bathing has been credited with many health benefits [2], predominantly for the cardiovascular system. However, the actual evidence has been limited to just a few studies, most of them populational. One non-randomized clinical trial found that a sauna session decreases blood pressure and improves several other aspects of cardiovascular function [3]. Another intervention that does that is exercise, and those two often go together, such as in a gym. This new study, like many other studies of its kind, was conducted in Finland, where the researchers set out to investigate whether exercise and sauna can work in synergy to improve cardiovascular health.

The design

This randomized, controlled trial included 47 participants aged 49 ± 9 years who, prior to the study, had low physical activity levels and at least one traditional cardiovascular risk factor. The participants were randomly assigned to three groups: the control group, the exercise group, and the exercise and sauna group. Importantly, there were no regular sauna users among the participants. The primary outcomes were blood pressure and cardiorespiratory fitness, and the secondary outcomes were fat mass, total cholesterol levels, and arterial stiffness.

The trial duration was eight weeks. The participants exercised three times a week for an hour (10 minutes warm-up, 20 minutes resistance training, and 30 minutes aerobic training), and in the exercise plus sauna group, these sessions were followed by a 15-minute visit to a sauna. The temperature started at 65 degrees Celsius, which is quite low for a sauna (the researchers probably wanted to be on the safe side) and was raised by 5 degrees every two weeks. Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured by maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max), a common metric in exercise studies.

Possible synergy

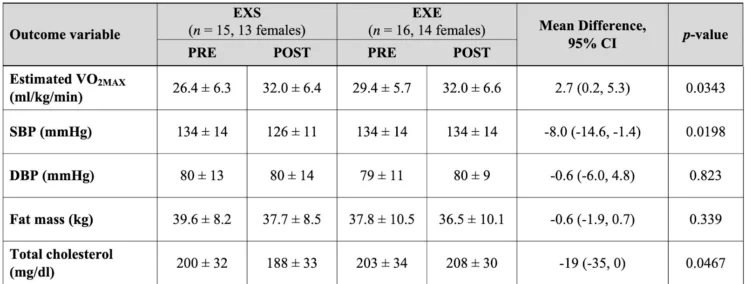

As expected, the exercise group surpassed the control group in cardiovascular fitness and weight loss, but there were no significant improvements in blood pressure and total cholesterol. Things were slightly better in the exercise plus sauna group, which showed a statistically significant improvement over the exercise group in VO2 max, systolic blood pressure, and cholesterol levels.

However, baseline VO2 max levels in the exercise plus sauna group were substantially lower than in the exercise group. This imperfect randomization makes it harder to assess the real intervention effect: it is possible that participants in the exercise plus sauna group experienced bigger gains in cardiovascular fitness due to their lower baseline fitness, and if this effect were accounted for, the already borderline statistical significance of the result would have vanished.

The decline in cholesterol levels was only borderline statistically significant as well. However, the decrease in systolic blood pressure was highly significant. This result is important: as research shows, such major drops in systolic blood pressure are associated with noticeable improvements in cardiovascular health.

Yet another obvious limitation that makes interpreting the results harder is the absence of a sauna-only group. Since sauna use alone has been found to decrease blood pressure, it is actually impossible to say whether the effect in this trial was additive, especially given that the exercise-only group fared no better in terms of blood pressure than controls.

However, previous sauna-only trials have shown more modest effect on blood pressure, so some synergy might have been at play in this new trial. Finally, all three groups were predominantly female. As geroscientists have learned over the recent decades, female and male “aging signatures” can differ substantially in animal models and possibly in humans.

The design of this experiment allowed us to ascertain to a reasonable extent, the additive effect of regular sauna exposure to exercise on cardiovascular health outcomes. These beneficial changes seen are promising, given that the essential methodological parameters of sauna exposure, such as duration and frequency were not only relatively short and tolerable, but practically feasible and replicable as well. Taken into context with mechanistic studies from molecular physiology, this is indicative of the noteworthy potential that passive heat therapy has. In addition, this study opens up opportunities to investigate shorter bouts of regular exercise in conjunction with sauna use and lends support for regular sauna bathing to be a possible therapeutic alternative, particularly for those with compromised exercise capacities, and possibly other rehabilitation settings as well.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this randomized, controlled trial is one of the most robust studies on the health effects of sauna bathing. It mostly agrees with previous research and hints at the existence of a synergistic effect between sauna and exercise. While these results are not definitive, and more research is needed, they certainly give a good reason not to skip the sauna next time you visit your gym. Importantly, the study also confirmed the relative safety of saunas for people with cardiovascular risk factors.

Literature

[1] Lee, E., Kolunsarka, I. A., Kostensalo, J., Ahtiainen, J. P., Haapala, E. A., Willeit, P., … & Laukkanen, J. A. (2022). The effects of regular sauna bathing in conjunction with exercise on cardiovascular function: A multi-arm randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

[2] Laukkanen, J. A., Laukkanen, T., & Kunutsor, S. K. (2018, August). Cardiovascular and other health benefits of sauna bathing: a review of the evidence. In Mayo clinic proceedings (Vol. 93, No. 8, pp. 1111-1121). Elsevier.

[3] Lee, E., Laukkanen, T., Kunutsor, S. K., Khan, H., Willeit, P., Zaccardi, F., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2018). Sauna exposure leads to improved arterial compliance: findings from a non-randomised experimental study. European journal of preventive cardiology, 25(2), 130-138.