Shingles Vaccine May Protect Against Alzheimer’s

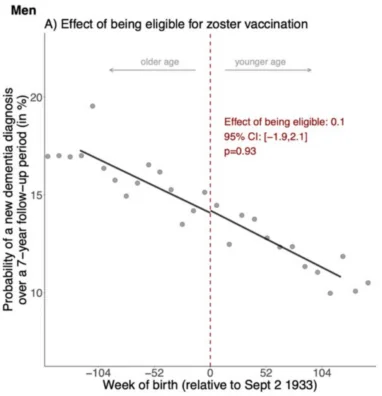

- These results were very sex-specific.

New research suggests that vaccination against shingles, a disease caused by the varicella zoster virus, can provide some protection against Alzheimer’s disease, mostly in women [1].

Viruses and aging

With causes of many age-related diseases remaining unclear, in recent years, scientists have been looking into the possible influence of bacteria and viruses. One new paper claims that “dozens of viruses, co-evolving with humans may actively distort human aging.” [2] In particular, herpesviruses have been suggested to contribute to the development of dementia. A study in mice showed that amyloid-ß, the misfolded protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease, may help protect the brain from those viruses, with long-term dementia being collateral damage [3].

If this theory is correct, antiviral medications and vaccines should be protective against dementia. However, showing such a connection is notably hard. Existing populational studies have yielded contradictory results due to methodological hurdles. For instance, willingness to get vaccinated is known to correlate with other health-conscious behaviors, which is something that’s difficult to account for in a statistical analysis.

Long live the queen’s bureaucracy!

This new study, published as a preprint that is yet to be peer reviewed, ingeniously exploits a case of medical bureaucracy to prove a causal relationship between vaccination against shingles (herpes zoster), a disease caused by the varicella zoster virus, and incidence of dementia.

In Wales, when introducing shingles vaccination for the elderly in 2013, an eligibility cutoff was made according to the exact date of birth. People born on or before September 2nd, 1933, were not eligible for the vaccine.

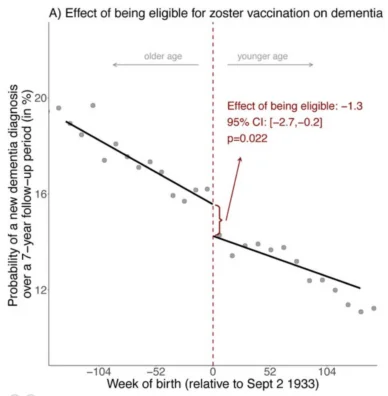

The researchers analyzed the medical records of people who were born up to one week before or after the cutoff date. Obviously, there was no reason for those two populations to differ in any respect except for their eligibility for the vaccine. Among people who were born after the cutoff date, 47% eventually got the vaccine.

This cutoff date provided perfect randomization, just like in a clinical trial, enabling the researchers to look for a causal connection. Using tens of thousands of medical records, the researchers showed that getting a vaccine lowered the probability of developing dementia of any kind by 20% during the follow-up period of 7 years.

Interestingly, the eligibility for zoster vaccine did not affect any other major cause of death or disability, suggesting that the virus only has a discernible effect on dementia. Despite the convincing study design, the researchers implemented several other analyses to rule out possible confounding factors. For instance, they made sure that no other medical intervention had the same eligibility threshold date.

Gender-specific effect

The results differed greatly by gender. In men, the effect was virtually nonexistent, while in women, it was greater than the average for both sexes. However, due to lesser statistical power, the researchers could not fully exclude the possibility that vaccination had some protective effect in men too. The rate of vaccination did not differ between the two sexes, and the effect of the vaccine on the incidence of shingles was similar as well.

Since women are known to be more prone to Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers stratified the results by types of dementia. They found that a shot of the shingles vaccine indeed provided statistically significant protection only against Alzheimer’s but not against vascular dementia or dementia of an unspecified type.

This study found that the zoster vaccine reduced the probability of a new dementia diagnosis by approximately one fifth over a seven-year follow-up period. By taking advantage of the fact that the unique way in which the zoster vaccine was rolled out in Wales constitutes a natural experiment, and meticulously ruling out each possible remaining source of bias, our study provides causal rather than associational evidence. Given that our effect sizes remain stable across a multitude of specifications and analysis choices, it is also improbable that our finding is a result of chance. The evidence provided by this study is, thus, fundamentally different to studies that have simply correlated (with adjustment for, or matching on, certain covariates) vaccine receipt with dementia.

Anti-Alzheimer’s vaccine?

This rare example of a randomized epidemiological study suggests that vaccination against shingles can provide a respectable degree of protection from dementia, especially from Alzheimer’s disease, at least in women. The question of how exactly unchecked varicella zoster virus contributes to Alzheimer’s will have to be studied further. Notably, this research focuses on an older type of shingles vaccine called Zostavax. The newer vaccine, Shingrix, did not become available in the UK before the end of the study’s follow-up period.

Literature

[1] Eyting, M., Xie, M., Heß, S., & Geldsetzer, P. (2023). Causal evidence that herpes zoster vaccination prevents a proportion of dementia cases. medRxiv, 2023-05.

[2] Teulière, J., Bernard, C., Bonnefous, H., Martens, J., Lopez, P., & Bapteste, E. (2023). Interactomics: Dozens of Viruses, Co-evolving With Humans, Including the Influenza A Virus, may Actively Distort Human Aging. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 40(2), msad012.

[3] Eimer, W. A., Kumar, D. K. V., Shanmugam, N. K. N., Rodriguez, A. S., Mitchell, T., Washicosky, K. J., … & Moir, R. D. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease-associated ß-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron, 99(1), 56-63.