Simply Being Overweight May Not Be Harmful in Aging

- Having very large amounts of any kind of mass appears to be dangerous.

According to a new large-scale populational study, being overweight is not associated with either significant risks or benefits between the ages of 45 and 85. Obesity, however, is a clear risk factor [1].

BMI plus fat mass index

While obesity is widely recognized as a life-long risk factor, several studies suggest that people who are simply overweight might be at a lower risk of death than their lean counterparts [2], especially at older ages [3]. However, many scientists attribute these results to a failure to account for variables such as body shape and long-term shifts in BMI (body mass index). The debate is far from settled, and this new study provides yet another angle.

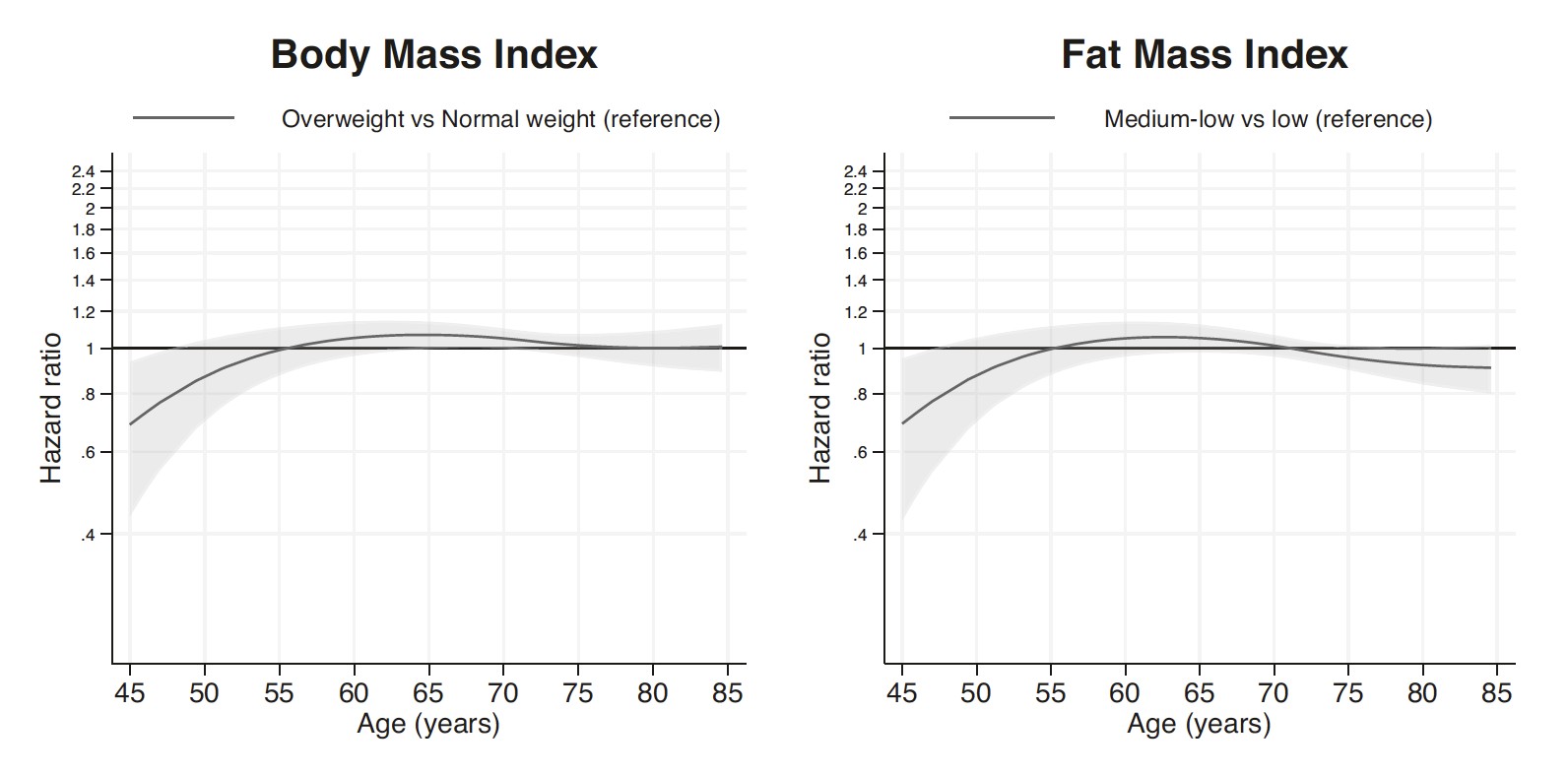

The authors used UK Biobank, a vast repository of health data on almost half a million British citizens, to analyze the association between being overweight or obese and the risk of death at various ages, from 45 to 85. To address another common claim, that BMI does not always reflect body composition (muscular people can have high BMIs without actually being obese), the researchers used an additional metric: fat mass index. This is calculated the same way as BMI but using only fat mass.

The researchers adjusted their model for an impressive array of potential confounders, including physical activity, dietary patterns, smoking, history of disease, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, and even salt consumption and leisure-time screen use. The final analysis included about 370,000 people. The participants were categorized by BMI as underweight (under 18.5 kg/m^2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m^2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m^2), obesity class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m^2), and obesity class 2 (at least 35 kg/m^2).

A bit of extra weight seems benign

The results showed that being overweight, both according to BMI and fat mass index, was only moderately associated with mortality risk at any given age. While an inverse association was indeed observed at ages 45 to 55, the statistical power in this age group was considerably lower due to fewer deaths. The graph shows a small bump in mortality risk for overweight people between ages 55 and 75, but this association vanishes according to BMI and is reversed according to fat mass index in older people. The researchers add a caveat to this last observation, saying that “the magnitude of association was small and may not be clinically meaningful”.

The picture was much clearer for obesity, especially extreme obesity, which was highly associated with mortality, even at younger ages. When measured by BMI, the association barely changed across all age groups, and it became only slightly attenuated with age when measured by fat mass index:

The main upshot of the study, according to its authors, is that obesity should be prevented at any age, while the association between being overweight and mortality is more nuanced. The researchers also note that while BMI and fat mass index showed a slightly different picture, those differences were small, and the correlation between the two indices stood at ≥0.93. Hence, BMI can be safely used as a measure of adiposity in future studies.

Surprising high lean mass results

Regarding the attenuation of the relationship between fat mass and mortality in the oldest participants, the researchers suggest a methodological explanation. First, people who reach old age despite their obesity might be genetically well-protected from its harmful effects. Second, at this point, the risk of cancer, cardiovascular diseases and frailty is so high that body composition becomes a relatively less important factor.

Interestingly, the researchers found the group with the highest lean mass (i.e., the most muscle) at a 20% to 30% higher risk of mortality from 55 to 75 years, which is consistent with some previous studies [4]. If these results are accurate, they pose an interesting question of why supposedly fit people with very high lean mass are at an increased risk. According to the researchers, “previous authors have suggested that muscle quality matters more than quantity when it comes to cardiometabolic health, and future research should consider factors such as microvasculature, muscle fiber type distribution and size, fat infiltration, and fat-free mass function.”

Conclusion

By adding stratification by age, this study paints a clearer picture of the relationship between adiposity and mortality risk with aging. According to the results, being overweight neither significantly increases nor decreases mortality risk. Obesity, however, seems to be equally harmful at all ages. While this might be the largest such study to date, it still has all the usual limitations of a populational study and cannot establish causation.

Literature

[1] Sanchez-Lastra, M. A., Ding, D., Dalene, K. E., del Pozo Cruz, B., Ekelund, U., & Tarp, J. (2023). Body composition and mortality from middle to old age: a prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank. International Journal of Obesity, 1-8.

[2] Flegal, K. M., Kit, B. K., Orpana, H., & Graubard, B. I. (2013). Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama, 309(1), 71-82.

[3] Doehner, W., Clark, A., & Anker, S. D. (2010). The obesity paradox: weighing the benefit. European heart journal, 31(2), 146-148.

[4] Lagacé, J. C., Brochu, M., & Dionne, I. J. (2020). A counterintuitive perspective for the role of fat‐free mass in metabolic health. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 11(2), 343-347.