The Effects of Physical Activity on Frailty

- Too much exercise puts stress on the joints.

A new study shows that even low levels of physical activity are very good for your muscles, bones, and joints, but exercising too much can potentially harm you [1].

The unholy trinity

Sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and osteoarthritis are the trio of age-related diseases that affect, respectively, muscles, bones, and joints. Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength. Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone density and deterioration of bone tissue. Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disorder that leads to degeneration of cartilage.

None of these diseases is deadly by itself, but they can drastically decrease the quality of life in old age. They are also known comorbidities for other diseases of aging – for instance, osteoarthritis is associated with a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular mortality [2]. The promise of geroscience is to extend healthspan along with lifespan so that people do not spend the last part of their lives in frailty and misery. To fulfill this promise, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and ostreoarthritis must be addressed.

Quantifying activity

This new study uses the NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) database, a treasure trove of various health data collected from hundreds of thousands of Americans since the 1960s. Interestingly, although NHANES and some similar databases have been around for decades, today’s researchers can derive new insights from this old data thanks to advances in AI and computing power.

Previous studies have attempted to elucidate the relationship between the three diseases and physical activity, but the results were often inconclusive. This new study is different because it stratifies the dataset by four levels of physical activity: very low (VLPA), low (LPA), medium (MPA), and high (HPA). These levels were defined by the amount of MET minutes per week. MET stands for “metabolic equivalent of task”. 1 MET is equal to the amount of energy the body spends while at total rest, such as lying on a couch watching TV. Even sitting at a desk bumps up energy expenditure to 1.3 MET.

Here are some examples: both brisk walking and weight training with heavier weights score at 5 MET, bicycling on flat terrain is equivalent to 9 MET, and running is one of the most energy-consuming activities at 11.5 MET; 1 minute of running uses up 11.5 MET-min worth of energy.

In this study, VLPA was defined as getting less than 150 MET-min physical activity per week (on top of basic daily movement), LPA as 150-960 MET-min per week, MPA as 961-1800 MET-min per week, and HPA as more than 1800 MET-min per week. The researchers note that this is in accordance with the methodology used in many previous studies.

How much PA is too much?

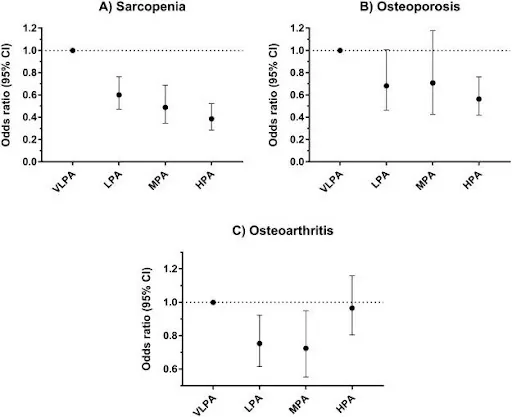

Studying a representative subset of the NHANES database, the team established the overall prevalence of sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and osteoarthritis in 50+ year old Americans to be 16.9%, 4.9%, and 29.1%, respectively. The prevalence of the three diseases in the VLPA, LPA, MPA, and HPA groups was, respectively, 24.6%, 14.8%, 11.2%, and 9.1% for sarcopenia; 8.0%, 4.9%, 4.4%, and 2.7% for osteoporosis; and 35.1%, 27.0%, 25.3%, and 26.9% for osteoarthritis. After adjusting for multiple variables (age, sex, race/ethnicity, annual household income, educational level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI) the researchers arrived at this general picture:

Judging from these results, light physical activity is enough to significantly lower the risk of all three diseases. For sarcopenia, there is a steady decline in the odds ratio all the way from LPA to HPA, although the difference remains relatively small. For osteoporosis, there are no significant benefits when moving up from LPA to MPA, and HPA isn’t much better than LPA. Previous research shows similar association of PA levels with all-cause mortality: even low levels of physical activity bring significant benefits, while the difference between low and high levels is less pronounced [2].

Osteoarthritis, though, was the oddball among the three: while LPA and MPA significantly lower its risk, HPA brings it back almost to VLPA levels. This is probably because strenuous physical activity causes the wear and tear of cartilage. While at lower levels of physical activity, benefits for cartilage (such as decrease in inflammation) outweigh the drawbacks, high PA levels apparently do more harm than good.

Conclusion

There are two major takeaways from this new study. First, in terms of the risk of getting one or more of these degenerative diseases of aging, low levels of physical activity are much better than nothing and only slightly worse than higher levels. Second, for osteoarthritis, the most prevalent disease among the three, there is such a thing as too much physical activity.

Literature

[1] Perez-Lasierra, J. L., Casajús, J. A., González-Agüero, A., & Moreno-Franco, B. (2021). Association of physical activity levels and prevalence of major degenerative diseases: Evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2018. Experimental Gerontology, 111656.

[2] Veronese, N., Cereda, E., Maggi, S., Luchini, C., Solmi, M., Smith, T., … & Stubbs, B. (2016, October). Osteoarthritis and mortality: a prospective cohort study and systematic review with meta-analysis. In Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism (Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 160-167). WB Saunders.

[3] Mok, A., Khaw, K. T., Luben, R., Wareham, N., & Brage, S. (2019). Physical activity trajectories and mortality: population based cohort study. Bmj, 365.