“The Perfect Diet” May Increase Lifespan by 13 Years

- This analysis is built from many population studies.

Scientists from Norway have built a model that predicts the effect of various dietary changes on human lifespan [1].

Diet is obviously a major health factor, but quantifying its impact is not easy. Since it is all but impossible to conduct a controlled study of how a particular type of food affects health in the long run, scientists have to resort to population studies, which are plagued by the abundance of confounding factors. On the other hand, the sheer number of dietary population studies might offset their imperfections. When dozens or studies and meta-analyses point in one direction, we should probably pay attention.

Meta-meta-analysis

This new study uses numerous meta-analyses, plus data from the vast Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study completed in 2019, to estimate the impact of various dietary changes on human lifespan.

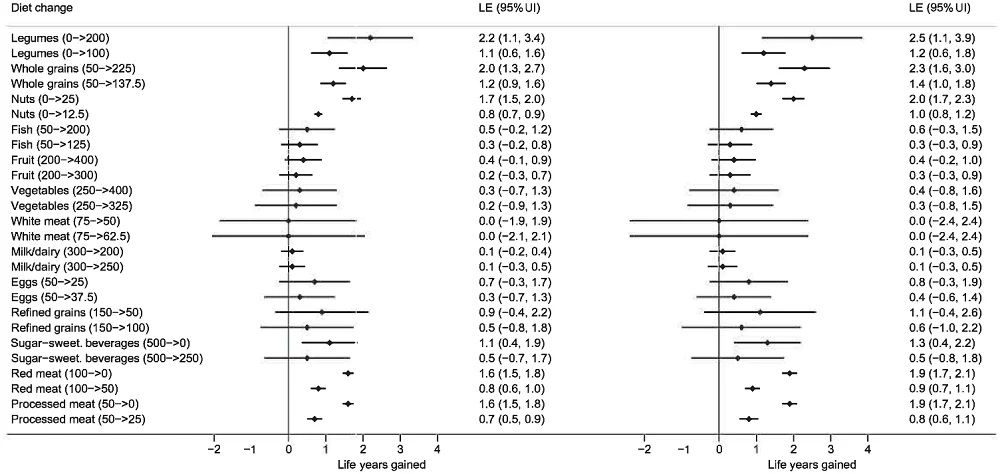

First, the researchers established a typical “Western diet”, based on the same population studies, and then built a model that estimates the effect of various changes to this diet that are started at the age of 20, 60, or 80. According to the model, if you are a 20-year-old woman, the increase in whole grain consumption from 50 grams (baseline Western diet) to 225 grams a day extends your life expectancy by two years. An increase in legume consumption from 0 to 200 grams a day results in an even more substantial 2.2-year extension, and boosting the consumption of nuts from 0 to just 25 grams a day gives you an additional 1.7 years of life; of course, extremely few people consume exactly zero legumes and nuts.

There are also gains to be made from decreasing the consumption of certain foods, including red meat and processed meat, which have been consistently reported to be harmful [2]. Under this model, reducing consumption from average Western levels (100 grams and 50 grams a day, respectively) to zero gives 1.6 additional years of life. On the other hand, increasing daily consumption of fish from 50 to 200 grams increases lifespan by 0.5 years. Large gains can also be achieved by cutting back on refined grains, sugary beverages, and eggs. Milk and white meat have little effect on lifespan.

Eating more fruits and vegetables is a good idea as well, but the gains are smaller, since the researchers calculated relatively high baseline amounts. Eating more fruit (400 grams instead of 200 grams a day) increases lifespan by 0.4 years, and more vegetables (400 grams instead of 250 grams) by 0.3 years. The results for men closely resemble those for women but are slightly more pronounced.

Overall, the researchers estimate that by following what they call “the optimized diet”, a 20-year-old woman can increase her life expectancy by 10.7 years, and a 20-year-old man can increase his by 13 years. If started at 60 years of age, the optimized diet supposedly increases lifespan by 8 and 8.8 years, respectively, and if started at 80, both sexes would benefit from a 3.4-year increase. The researchers also devised “the feasible diet”, which achieves considerable lifespan extension via less drastic changes.

Taken at face value, these results position healthy diet as the best geroprotective intervention available today. The researchers took an additional step and developed an online tool that helps calculate gains in lifespan you can achieve by making specific dietary changes. Here are the gains in lifespan for 20-year-old women (left) and men.

Better late than never

The results look rosy, but they are based on population studies, a specific methodology, and assumptions that may or may not be correct. For instance, the researchers assume that “the time to full effect”, which represents the start of a dietary change until it stops adding years to lifespan, is 10 years. While this assumption is based on the available data, the authors admit they might be wrong.

On the other hand, the study sits well with previous research. Interestingly, scientists are slowly finding biological evidence that backs some (but not all) dietary populational studies. As an example, recently, a genetic mutational signature was found that firmly links both processed and unprocessed red meat to colorectal cancer [3] – something that population studies have been suggesting for a long time.

Another major takeaway from the study is that while it is better to start eating healthy as early as possible, it is also never too late, with gains in lifespan remaining very substantial even for 60-year-olds.

Conclusion

This study is probably the first ever to propose a model that calculates gains in lifespan from several dietary interventions, an intriguing undertaking that might become a basis for future research.

Literature

[1] Fadnes, L. T., Økland, J. M., Haaland, Ø. A., & Johansson, K. A. (2022). Estimating impact of food choices on life expectancy: A modeling study. PLoS medicine, 19(2), e1003889.

[2] Pan, A., Sun, Q., Bernstein, A. M., Schulze, M. B., Manson, J. E., Stampfer, M. J., … & Hu, F. B. (2012). Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Archives of internal medicine, 172(7), 555-563.

[3] Gurjao, C., Zhong, R., Haruki, K., Li, Y. Y., Spurr, L. F., Lee-Six, H., … & Giannakis, M. (2021). Discovery and features of an alkylating signature in colorectal cancer. Cancer discovery, 11(10), 2446-2455.