The right to die and the right to live

On May 10 this year, Australian ecologist David Goodall took his own life before aging could. The scientist, aged 104, reportedly said he “regretted” having reached that age, because the quality of his life had significantly deteriorated as a consequence of his declining health. Unhappy with his condition, though not suffering from any terminal disease—except for aging itself—Goodall opted to end his life through assisted suicide. As the practice is currently not allowed in Australia, he flew with friends and family all the way to a clinic in Switzerland, where he flipped a switch and administered his own lethal injection while listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Interestingly, the cost of his trip to Switzerland was covered with money collected through a crowdfunding campaign.

A matter of rights

Goodall was a lifelong supporter of euthanasia, and both he and his fellows from Exit International—a non-profit organization advocating the legalization of voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide—said that people should have the right to die with dignity when they feel the time has come.

As he himself put it, the elderly scientist didn’t have much time left anyway, and, given the circumstances, this is an understandable choice. Given the current state of rejuvenation medicine, there was no chance he could ever benefit from it; the odds are that he might have never heard of it. This was his personal choice, and I doubt I would have made the same one, but there is rather little point to life when it is reduced to prolonged suffering with no hope of improvement and a near certainty of worsening. This suffering is both physical and psychological, as in advanced old age, you have to come to terms with the fact that the person you used to be is really no more and what you loved doing is now beyond your capabilities. If the situation really is so dire and grim, and all hope for a better life is utterly lost, then euthanasia should be an available option. Hopefully, cryonics might one day become a reliable lifeline to make euthanasia unnecessary, but as your life really is your own and nobody else’s, you should have the right to decide to terminate it if you see fit, provided your judgment is not impaired in any way.

On the page of Dr. Goodall’s crowdfunding campaign, there is a striking bolded sentence. It reads “All rational adults deserve a peaceful death at a time of their choosing.” Assuming that a person desires death for whatever reason, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be peaceful; why make it worse than it has to be? (As a side note, the fact there are organizations campaigning for the right of people to have a “good death”—which is exactly what the Greek word “euthanasia” means—betrays the already obvious fact that death isn’t generally very good.) Making death peaceful is already well within our technical abilities; the only obstructions are some obsolete legal frameworks. However, it’s the “at a time of their choosing” part that’s worrisome—as things stand, you can choose to hasten your death, but you can’t really choose to postpone it. If a rational adult chose age 200 as his or her preferred time of death, this right to choose couldn’t currently be honored. Shouldn’t we fight for this right as well?

More similar than you think

Naturally, the battles for euthanasia and for life extension are fought against two different foes. The former is a battle against inconsiderate laws; the latter is a battle against the limitations that nature didn’t bother removing. However, the two causes share a common goal.

Crowdfunding someone’s death is, intrinsically, somewhat disturbing, and there is a stark contrast between the kind of crowdfunding that Lifespan.io does, which is aimed at giving people longer, better lives, and what Exit International did in this case. However, the goal of the crowdfunding campaign for Goodall’s trip to Switzerland wasn’t that of terminating his life; the goal was terminating his suffering, and, at that point, this goal could only be achieved through death. Because of this, I commend Exit International and the campaign backers for allowing Goodall to free himself of his pain as he wished.

The shared goal of life extension and euthanasia is to end pointless suffering. Life extension, being basically nothing more than next-generation medicine, is meant to eliminate unnecessary suffering the old-fashioned way: eliminating the diseases that cause it. Unlike other types of medicine, though, the diseases in the crosshairs of life extension are age-related diseases, and to prevent them, it is imperative to attack aging itself. On the other hand, euthanasia is an extreme solution, the last resort that may be used when all else has failed and a person is ready to pay the highest price to be relieved from useless, unbearable suffering.

Because of this shared goal, it’s logical to believe that people willing to donate to ending Dr. Goodall’s suffering would also donate towards ending age-related diseases, thus helping to prevent the terrible suffering that results in euthanasia becoming a sensible choice.

The obvious reality of aging

In some pictures taken shortly before his death, Goodall sports a jumper with a tag reading “Ageing disgracefully”. His arthritis was bad enough that, in a somewhat bitter twist of irony, he didn’t even manage to flip the lethal injection switch the first time. This jumper refers to the concept of “aging gracefully”, which is largely a myth. A healthy lifestyle, combined with winning the genetic lottery, may certainly make your aging less worse than others’; however, the chronic diseases of aging don’t all happen because most people have unhealthy lifestyles or got unlucky with their genes. They happen because aging is, by definition, a chronic, progressive process of deterioration and loss of functionality. However “gracefully” you may be deteriorating—whatever that means—it will always, invariably, kill you. Think about it: however gracefully or disgracefully aging is happening in your body, it is always, with absolutely no exception whatsoever, serious enough to eventually cause death.

Sometimes—too often, in fact—aging is disgraceful enough that not everyone is willing to wait until the end. Goodall himself waited quite a while, but he eventually decided to check out before aging could make his life any more miserable. The popular comedian Robin Williams, struck by an unusually aggressive form of Lewy body disease, did so much earlier and in a more tragic fashion—he hung himself at age 63. He couldn’t bear with how his condition was eating away his mental faculties.

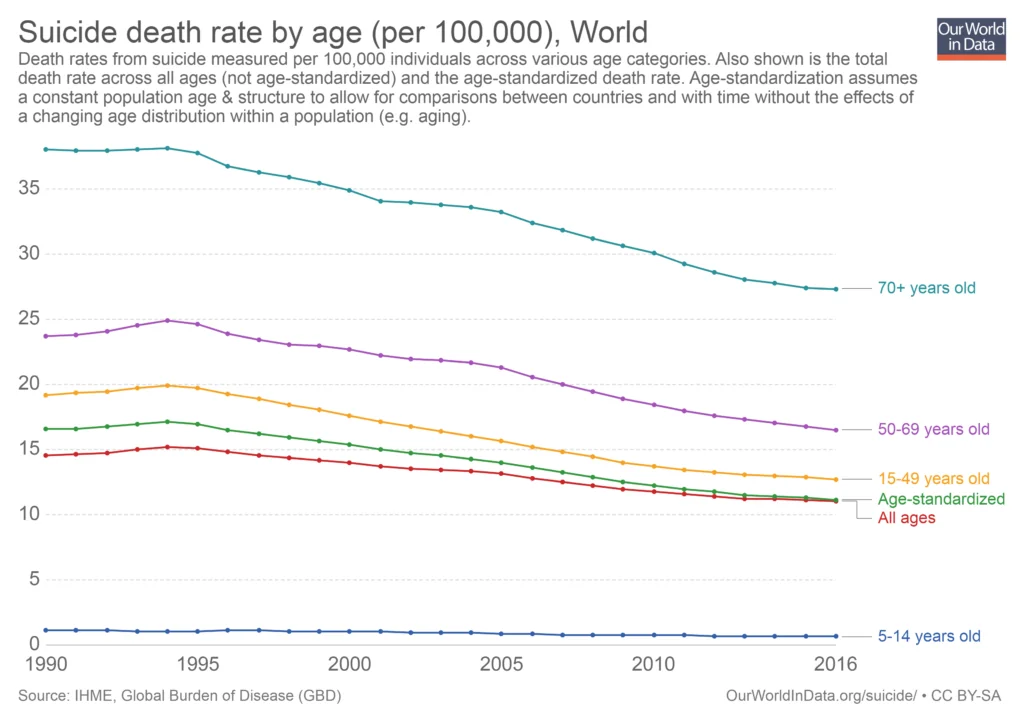

Neither Goodall nor Williams were alone. Although suicide rates in general have been slowly but steadily decreasing during the past 30 years or so, suicide rates among the elderly are, by far, the highest in the world, as can be seen from the chart below (courtesy of Our World In Data).

In 2016, 27 out of every 100,000 people aged 70 and older took their own lives. If that doesn’t seem like much, the grand total of people in that age cohort who committed suicide that year was over 110,000. Given that aging kills just about that number of people in one day, it’s a bit as if 2016 had one extra day when everyone over the age of 70 who died did so at their own hand. From the same source, here is the breakdown of suicides by age range since 1990.

Younger people constitute a larger portion of the total suicides each year—somewhat unsurprisingly, since at the moment world population is comprised of far more people below age 60 than above—but suicides from age 50 and up still accounted for nearly 40% of the total in 2016.

Research on suicide among the elderly is still somewhat neglected, though loss, loneliness, and psychological as well as disability and physical disease are all contributing factors, particularly among older white men, who are especially likely to take their own lives [1]. Despite the lack of data, you don’t have to be a clairvoyant to realize that losing your friends and relatives (who are dying of aging just every bit as you are), being disabled, having a chronic illness that can only get worse, and feeling cut out from the world all have extremely good chances of making you depressed and your life less worth living; worse, they can make it unbearable to be alive.

Double standards

The general attitude toward death is interestingly ambivalent. The WHO website speaks of suicide in terms of something that can and should be prevented. We have suicide hotlines that you can call for help if you’re having suicidal thoughts. Euthanasia, as we have seen, is a very controversial topic, and it’s frowned upon and largely prohibited even when patients actively don’t want to live anymore and there’s no hope for their conditions to improve. This might be due to the rather clear fact that, if a person wishes to die, there’s quite likely something very bad going on in his or her life, and as there’s no going back once the plug has been pulled, we feel that it’s advisable to try to solve whatever problem is causing suicidal wishes—especially since people who feel suicidal may easily see reality as being far bleaker than it is, their judgement being clouded by their intense desire to put an end to their pain.

You’d think that, given this premise, we should be a society that strives to prevent death by all possible means, putting more effort into addressing the leading and more widespread causes of death. This is indeed what we do in most cases; aging is the only exception to the norm. If someone was letting himself die by starvation, no matter his age, we’d call that suicide and urge him to seek help; we’d do the same if someone was letting herself die by refusing treatment for a lethal though curable condition. On a grander scale, though, most people don’t consider the acceptance of age-related death to be suicide; they call it the “natural cycle of life”, the “completion of an arc”, “walking into the sunset”, and similar things. Why is that? If we, as a society, insist that people don’t give up on their lives, however hard the times they’re going through may be, why do we demand that everyone should give up on life in old age, rejecting the idea of even trying to prevent all these deaths? If a young person, however sick or desperate, should not let go because he or she still has so much time ahead and there’s so much left to accomplish, why should we consider the life of an 80 year old to be “complete” and ripe for termination by aging? Instead, shouldn’t we attempt to give this person the same health of a youngster and abundant time to live? The idea itself that life could ever be complete, as if it were a sticker album, is laughable—besides, when you complete an album, you can always get a new one if you want to. Maybe, one day, you might feel like you’ve had enough of attaching stickers, but you should have the option to keep going if you so wish.

The third option

Goodall was faced with only two options to end his suffering: waiting for his health to deteriorate enough to cause his death, making whatever was left of his life even more miserable, or choosing a quick, painless death. He chose the latter course of action because his failing body was making him unhappy. However, what if his body hadn’t been failing him? What if he had been in perfect health, completely able-bodied and disease-free? Would he have felt that the time was ripe for him to die just because he was 104? This would be for him, and others in the same situation, to decide, but he didn’t have this chance. None of us do. We can’t currently decide to live for however long we see fit; in a best-case scenario, we can only choose which way to die. Life extension biotechnology could give us a third option: preserving our health, potentially indefinitely, allowing us to choose life rather than the least worse of two deaths.

Simply trying to keep the elderly engaged, suggesting that they attend yoga or computer classes, making resolutions to spend more time with our aged parents or grandparents, or providing them with better, cheaper nursing homes doesn’t cut it. These measures, although better than nothing, won’t give old people their health back and won’t, as a rule, spare them a forced choice between two evils. Forget about wishy-washy solutions; if we really care about our elderly, then it’s time to take life extension seriously.

Literature

[1] Alves, V. D. M., Maia, A. C. C., & Nardi, A. E. (2014). Suicide among elderly: a systematic review. MedicalExpress, 1(1), 9-13.