A Switch to Whole Food Diets Benefits Elderly People

- Most positive changes can be observed in all treatment groups regardless of macronutrient ratios and protein source.

New research demonstrated how transitioning from a typical Western diet composed of processed foods to a whole-food diet improved cardiometabolic health and body composition and impacted gut microbiome metabolites in elderly people [1].

You are what you eat

While this study was conducted in Australia, the foods commonly consumed there are similar to common foods in the United States and many other parts of the world. As the authors noted, this Western diet is composed mostly of industrially processed foods, is high in refined sugar, salt, and saturated fat, and is low in protein and fiber. This diet is a well-known contributor to obesity, comorbidities, and increased all-cause mortality [2, 3].

On the other hand, whole-food diets and plant-derived foods have been found to positively impact health [4]. Those diets are rich in fiber, micronutrients, phytochemicals, complex carbohydrates, and plant proteins that are usually absent in Western diets.

The authors also pointed out that the quality and ratios of macronutrients are important for a healthy diet. There has also been substantial research into plant and animal protein sources and the ratios of fats, carbohydrates, and protein in various diets.

Dietary interventions in the elderly

The authors of this 4-week randomized controlled trial aimed to assess the effects of plant or animal protein sources, the fat-to-carbohydrate ratio, and the impact of transitioning from a standard Western diet to a whole-food diet, which has not been previously assessed in older individuals.

The study participants were 113 healthy individuals between the ages of 65 and 75. The participants were divided into four groups, each following a different diet: omnivorous (which includes plant and animal food) with high fat, omnivorous with high carbohydrates, semi-vegetarian with high fat, and semi-vegetarian with high carbohydrates. Access to food was not limited. Diets were carefully planned to match energy and protein concentration and followed the same menu. However, specific items were tailored to match a treatment group. Participants kept food records regarding the amount of food consumed.

Major health improvements

The authors noted “improvement across all measured health domains independent of diet treatments.” They hypothesize that transitioning from a Western diet to a whole-food diet is greatly responsible for the observed improvements.

The researchers observed that participants’ total energy intake and appetite didn’t change during the study. However, the levels of FGF-21, a marker of protein appetite, were significantly changed. Reducing protein consumption by 21% increased the FGF-21 levels by 25%.

Previous research observed that lowering protein intake usually results in increasing total food intake as a compensatory mechanism, and this seems to be particularly common in environments with plenty of unhealthy food options. This study seems to agree with those observations, as the researchers observed a 5% increase in food intake. Additionally, participants with high baseline FGF-21 levels exhibited high protein appetite during the study.

Despite not observing significant changes in energy consumption, the researchers observed changes in the participants’ body composition: a 3% reduction in body weight, a 5% reduction in fat mass, and a 0.7% reduction in lean mass (including muscle mass). This modest reduction in fat-free mass didn’t affect muscle strength; on the contrary, tests on muscle function showed improvement.

The authors also note that participants lost, on average, 1.7 kilograms (3.7 pounds) in the week preceding the study. During that week, the participants were tasked with recording their normal food intakes, which served as their baselines for this study. Just the act of recording food intake may lead to weight loss, as participants unintentionally improve their diets or reduce the amount of food they eat in order to lessen the burden of recording it. If this baseline is already improved compared to participants’ actual diets, then the outcomes of the dietary intervention might be underreported. This baseline weight loss might have resulted from reduced alcohol consumption during the study.

The researchers also investigated markers of cardiometabolic health. They observed that the participants who consumed more vegetarian diets had the greatest reductions in diastolic blood pressure. They also observed some positive changes in all study groups, including systolic blood pressure; total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol; insulin level: and insulin resistance. These observations agree with previous research that links plant-based diets with better cardiometabolic health.

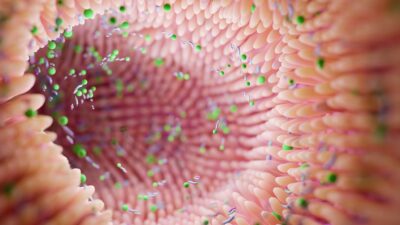

Treats for the gut microbiota

Food in the gut also feeds the armies of various microbes that live in the intestines. Among other factors, the numbers of various species is dependent on what they are fed, so these researchers investigated how the gut flora changed. The omnivorous, high carbohydrate group experienced the biggest change in gut microbiome diversity. However, all dietary interventions led to increased production of bacterial metabolites from the fermentation of dietary fiber, which aligns with the reported increase in fiber consumption. Those metabolites “have been associated with better health outcomes, conferring protective effects in inflammation, cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.”

The authors note that the relatively short duration of this study and the limited number of fecal samples collected for the analysis might not be sufficient to observe major changes to the gut microbiome. Other major factors impacting this microbiome were also not accounted for in this study.

In conclusion, our observational results suggest that transitioning from a “standard Australian diet” to feasible alternatives-whether moderately higher or lower in F:C [fat to carbohydrate] and predominantly plant- or animal-based can improve several health markers relevant to older age. This demonstrates that a healthy diet rich in fruit, vegetables, fibre, moderate amounts of protein, regardless of their sources, while restricting alcohol and highly processed food, can be beneficial for various health domains in older adults. Furthermore, PBD [plant-based-diet] appears to offer additional benefits for cardiometabolic health.

Literature

[1] Ribeiro, R. V., Senior, A. M., Simpson, S. J., Tan, J., Raubenheimer, D., Le Couteur, D., Macia, L., Holmes, A., Eberhard, J., O’Sullivan, J., Koay, Y. C., Kanjrawi, A., Yang, J., Kim, T., & Gosby, A. (2024). Rapid benefits in older age from transition to whole food diet regardless of protein source or fat to carbohydrate ratio: Arandomised control trial. Aging cell, e14276. Advance online publication.

[2] Ludwig, D. S., & Ebbeling, C. B. (2018). The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity: Beyond “Calories In, Calories Out”. JAMA internal medicine, 178(8), 1098–1103.

[3] Schnabel, L., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Touvier, M., Srour, B., Hercberg, S., Buscail, C., & Julia, C. (2019). Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Mortality Among Middle-aged Adults in France. JAMA internal medicine, 179(4), 490–498.

[4] Song, M., Fung, T. T., Hu, F. B., Willett, W. C., Longo, V. D., Chan, A. T., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA internal medicine, 176(10), 1453–1463.