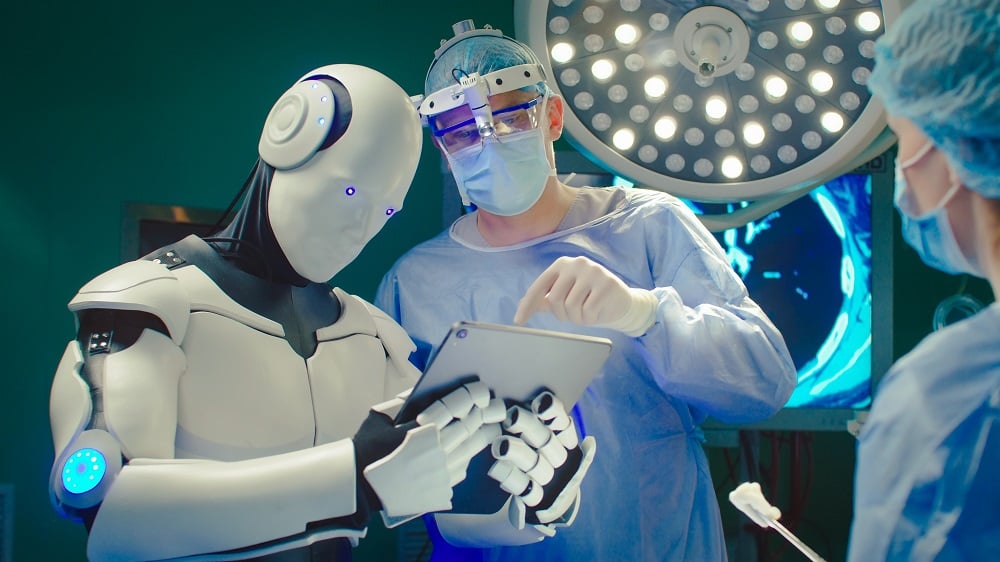

AI Outperforms AI-Assisted Doctors in Diagnostic Reasoning

- GPT was found to be far more accurate than the average physician.

In a new study, ChatGPT 4.0 achieved significantly better diagnostic scores when evaluating complex cases than either unassisted human physicians or physicians who consulted the chatbot [1].

Bad news for human doctors?

For millions of people, chatbots powered by large language models (LLMs) have quickly become an indispensable source of information on everything from finances to relationships. These digital aids often come across as more knowledgeable, polite, patient, and compassionate than human experts.

It has been questioned, however, if it is really a smart idea to turn to a robot for medical advice. In what could be a troubling sign for general practitioners, chatbots have shown they can outperform humans in this area too. A study from May of last year found that the earlier version of ChatGPT, 3.5, handily outclassed human health professionals in answering patients’ questions. Responses from both the bot and verified physicians were graded by a panel of health experts, and the gap was striking: for instance, 27% of human answers were deemed “unacceptable” compared to just 2.6% of machine-generated ones.

That study had relied on doctor responses pulled from Reddit, but a more recent study went further. Earlier this year, researchers at Google developed a dedicated model called Articulated Medical Intelligence Explorer (AMIE) and tested it against human primary care practitioners. Wide-ranging health scenarios were distributed at random, with actors playing the roles of patients who discussed their cases with either the chatbot or a human physician without knowing who was who. According to expert evaluators, AMIE outperformed its human counterparts in 24 of 26 categories, including empathy.

“Meet my assistant, ChatGPT”

In a new study published in JAMA Network Open, Stanford researchers stripped AI of its perceived edge in empathy and bedside manner. They eliminated the patient interaction element entirely, tasking either ChatGPT 4.0 or 50 human physicians (26 attendings and 24 residents) with diagnosing six carefully selected cases. These cases had never been published before, ensuring that the LLM could not have encountered them during training.

Here’s the twist: half of the doctors were allowed to consult ChatGPT. The aim was to gauge whether physicians would embrace AI as an assistant and whether doing so would improve their diagnostic reasoning. All participants could also use conventional resources like medical manuals.

The primary outcome was a composite diagnostic reasoning score developed by the researchers, which measured accuracy in differential diagnosis, the appropriateness of supporting and opposing factors, and next diagnostic steps. Secondary outcomes included time spent per case and final diagnosis accuracy.

In the end of the day, the LLM dominated yet again, with a median score of 92% per case: 14 points higher than the non-LLM-assisted human group. It also achieved 1.4 times greater accuracy in the final diagnosis. Interestingly, the group of physicians consulting the chatbot didn’t fare much better than their non-assisted peers, scoring 76% versus 74%.

Why didn’t consultation work?

The researchers had anticipated that consulting the LLM would give physicians a marked advantage, but that wasn’t the case. “Our study shows that ChatGPT has potential as a powerful tool in medical diagnostics, so we were surprised to see its availability to physicians did not significantly improve clinical reasoning,” said study co-lead author Ethan Goh, a postdoctoral scholar in Stanford’s School of Medicine and research fellow at Stanford’s Clinical Excellence Research Center.

Why the lackluster collaboration? The authors suggest a few reasons. First, participants weren’t simply asked to provide a diagnosis. Instead, they had to demonstrate diagnostic reasoning by suggesting three possible diagnoses and explaining how they reached their final choice. The chatbot excelled at this aspect, while humans sometimes struggled to articulate their thought processes. This echoes longstanding challenges in modeling human diagnostic reasoning in computer systems before the advent of LLMs.

“What’s likely happening is that once a human feels confident about a diagnosis, they don’t ‘waste time or space’ on explaining their reasoning,” said Jonathan H. Chen, Stanford assistant professor at the School of Medicine and the paper’s senior author. “There’s also a real phenomenon where human experts can’t always articulate exactly why they made the right call.”

Another hurdle was that physicians often dismissed valid suggestions from their AI co-pilot, a sign that overcoming the natural sense of superiority toward machines may take time.

Finally, the researchers noted that the chatbot’s performance hinges on the quality of the prompts it receives. The research team crafted sophisticated prompts to get the most out of ChatGPT, while human participants often used it more like a search engine, asking short, direct questions instead of providing full case details. “The findings suggest there are opportunities for further improvement in physician-AI collaboration in clinical practice and health care more broadly,” Goh said.

One intriguing secondary finding was that doctor-LLM pairs completed cases slightly faster than doctors working solo. While, according to the paper, the difference of slightly more than a minute was negligible, Goh argues that even a small efficiency gains could help make doctors’ lives more efficient. “Those time savings alone could justify the use of large language models and could translate into less burnout for doctors in the long run,” he said. However, more rigorous studies are needed to fully understand this potential benefit.

AI will not replace doctors (until it will)

The authors of studies like this one have been careful to emphasize that AI is not a true substitute for a human health practitioner. “AI is not replacing doctors,” Goh reassures. “Only your doctor will prescribe medications, perform operations, or administer any other interventions.”

Still, it may only be a matter of time before AI demonstrates superiority over human physicians in nearly every aspect of care. Furthermore, vast regions of the world currently face limited access to healthcare, leaving many people without the option of consulting a human doctor at all. In such contexts, AI could fill a critical gap. Just as some countries skipped the landline phase entirely and adopted mobile phones, they might also be the first to transition to predominantly AI-driven healthcare, facing fewer entrenched bureaucratic barriers.

Building on this study, Stanford University, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the University of Virginia, and the University of Minnesota have joined forces to create AI Research and Science Evaluation (ARiSE), a network dedicated to evaluating generative AI outputs in healthcare.

Literature

[1] Goh, E., Gallo, R., Hom, J., Strong, E., Weng, Y., Kerman, H., … & Chen, J. H. (2024). Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 7(10), e2440969-e2440969.