Different Risks for Men and Women’s Cardiovascular Health

- BMI, high blood pressure, and fructose are risk factors for both sexes.

In a recent paper published in Nutrients, the authors investigated longitudinal data regarding dietary and lifestyle factors that impact cardiovascular risk in males and females [1].

Cardiovascular disease risk factors

Aging, particularly vascular aging, is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [2]. Previous research has identified several factors that contribute to early vascular aging, including hypertension, psychological stress, and diet [3-6].

Therefore, the authors of the paper chose to analyze how such variables as consumption of sucrose, fructose, sodium, and potassium along with psychological stress in young adult males and females influence vascular aging and CVD risk later in life. They also analyzed sex as a variable, since previous research has suggested differences in CVD risk factors, CVD outcomes, and vascular aging are dependent on sex [7].

Shared risk factors

The authors of this retrospective observational study obtained the data of 2,656 racially diverse participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study conducted in the United States. As young adults, the study participants underwent carotid artery ultrasound, which was used to calculate a vascular aging index. Additionally, researchers analyzed demographics, dietary data, and depression scores, both from when participants were young and after a 20-year follow-up.

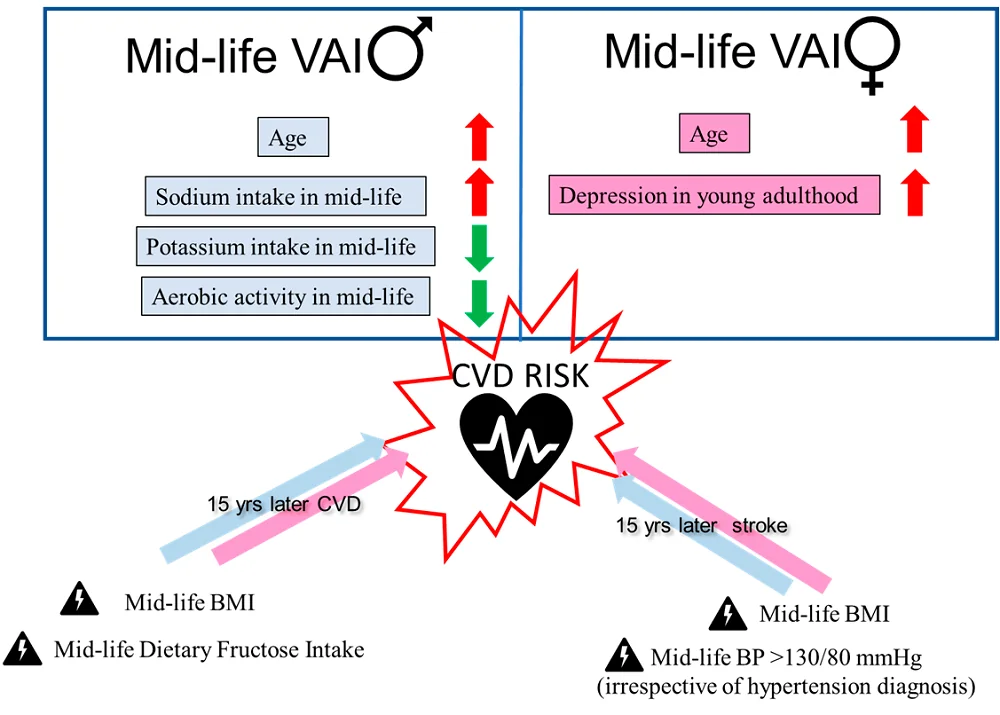

Analysis of the results showed that CVD, stroke, and death were significantly predicted by BMI in both males and females. Males and females also showed similarities regarding the association between high blood pressure at baseline and stroke risk. Specifically, the authors found that blood pressure higher than “130/80 mmHg in adolescence doubles the risk of having a stroke 35 years later.”

Fructose consumption at the 20-year follow-up was also found to be a risk factor for CVD in both sexes. The authors mention that “this is the first study to demonstrate in a longitudinal cohort that fructose, not sucrose, predicts CVD risk.” It is interesting that the authors found fructose, but not sucrose (dietary sugar), to be a risk factor for CVD, as sucrose is composed of equal proportions of glucose and fructose.

The authors elaborate on the role of fructose in vascular aging and CVD. Previous preclinical research has shown that “dietary fructose contributes to vascular stiffness both in adolescence and adulthood” [8-10]. It also reduces plasma insulin and leptin but increases ghrelin concentrations [11]. The authors speculate that such hormonal changes might contribute to obesity. Another analysis of six human cohort studies linked sugar-sweetened beverages to an increased risk of hypertension [12].

This data is specifically important since the composition of high fructose corn syrup, which is commonly used in the food industry in North America, is dominated by fructose [13-15].

Sex-specific risk factors

The authors emphasized the importance of looking into sex differences while studying CVD, as previous research already pointed to some differences. For example, males were shown to more frequently suffer from heart disease, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and stroke than age-matched females [16].

It’s hypothesized that sex hormones play the main role in such differences. The hypothesis is supported by the fact that in post-menopausal women, researchers observed increased occurrence of CVD and heart failure [17].

In the analyzed data, the researchers also observed sex-specific differences in vascular aging and CVD risk factors. The first difference pertained to psychological stress. In females, but not males, depression scores at baseline were associated with vascular aging.

They note that since depression scores in males and females didn’t statistically differ, this underscores the effect that depression has on vascular aging in females but not males. The authors also found it important to follow up on this observation when females transition to menopause.

On the other hand, in males, the vascular aging index was predicted by sodium intake at year 20 of follow-up. However, for potassium intake, there was an inverse correlation. The researchers also observed an inverse correlation for males who had at least one hour per month of aerobic exercise over the past year.

Sex-specific alterations in lifestyle

The authors conclude that based on their research, males and females might need different changes in dietary and lifestyle behaviors to benefit their cardiovascular health. However, both sexes also share some factors, such as BMI, that impact their health.

Literature

[1] Osborne, M., Bernard, A., Falkowski, E., Peterson, D., Vavilikolanu, A., & Komnenov, D. (2023). Longitudinal Associations of Dietary Fructose, Sodium, and Potassium and Psychological Stress with Vascular Aging Index and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the CARDIA Cohort. Nutrients, 16(1), 127.

[2] Mikael, L. R., Paiva, A. M. G., Gomes, M. M., Sousa, A. L. L., Jardim, P. C. B. V., Vitorino, P. V. O., Euzébio, M. B., Sousa, W. M., & Barroso, W. K. S. (2017). Vascular Aging and Arterial Stiffness. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia, 109(3), 253–258.

[3] Harvey, A., Montezano, A. C., Lopes, R. A., Rios, F., & Touyz, R. M. (2016). Vascular Fibrosis in Aging and Hypertension: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. The Canadian journal of cardiology, 32(5), 659–668.

[4] LaRocca, T. J., Martens, C. R., & Seals, D. R. (2017). Nutrition and other lifestyle influences on arterial aging. Ageing research reviews, 39, 106–119.

[5] Merz, A. A., & Cheng, S. (2016). Sex differences in cardiovascular ageing. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 102(11), 825–831.

[6] Sara, J. D. S., Toya, T., Ahmad, A., Clark, M. M., Gilliam, W. P., Lerman, L. O., & Lerman, A. (2022). Mental Stress and Its Effects on Vascular Health. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 97(5), 951–990.

[7] Connelly, P. J., Azizi, Z., Alipour, P., Delles, C., Pilote, L., & Raparelli, V. (2021). The Importance of Gender to Understand Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease. The Canadian journal of cardiology, 37(5), 699–710.

[8] Komnenov, D., Levanovich, P. E., Perecki, N., Chung, C. S., & Rossi, N. F. (2020). Aortic Stiffness and Diastolic Dysfunction in Sprague Dawley Rats Consuming Short-Term Fructose Plus High Salt Diet. Integrated blood pressure control, 13, 111–124.

[9] Komnenov, D., & Rossi, N. F. (2023). Fructose-induced salt-sensitive blood pressure differentially affects sympathetically mediated aortic stiffness in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Physiological reports, 11(9), e15687.

[10] Levanovich, P. E., Chung, C. S., Komnenov, D., & Rossi, N. F. (2021). Fructose plus High-Salt Diet in Early Life Results in Salt-Sensitive Cardiovascular Changes in Mature Male Sprague Dawley Rats. Nutrients, 13(9), 3129.

[11] Stanhope, K. L., Schwarz, J. M., Keim, N. L., Griffen, S. C., Bremer, A. A., Graham, J. L., Hatcher, B., Cox, C. L., Dyachenko, A., Zhang, W., McGahan, J. P., Seibert, A., Krauss, R. M., Chiu, S., Schaefer, E. J., Ai, M., Otokozawa, S., Nakajima, K., Nakano, T., Beysen, C., … Havel, P. J. (2009). Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. The Journal of clinical investigation, 119(5), 1322–1334.

[12] Jayalath, V. H., de Souza, R. J., Ha, V., Mirrahimi, A., Blanco-Mejia, S., Di Buono, M., Jenkins, A. L., Leiter, L. A., Wolever, T. M., Beyene, J., Kendall, C. W., Jenkins, D. J., & Sievenpiper, J. L. (2015). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 102(4), 914–921.

[13] Tappy, L., & Lê, K. A. (2010). Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiological reviews, 90(1), 23–46.

[14] Ventura, E. E., Davis, J. N., & Goran, M. I. (2011). Sugar content of popular sweetened beverages based on objective laboratory analysis: focus on fructose content. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 19(4), 868–874.

[15] Walker, R. W., Dumke, K. A., & Goran, M. I. (2014). Fructose content in popular beverages made with and without high-fructose corn syrup. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 30(7-8), 928–935.

[16] Tsao, C. W., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., Alonso, A., Beaton, A. Z., Bittencourt, M. S., Boehme, A. K., Buxton, A. E., Carson, A. P., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Elkind, M. S. V., Evenson, K. R., Eze-Nliam, C., Ferguson, J. F., Generoso, G., Ho, J. E., Kalani, R., Khan, S. S., Kissela, B. M., Knutson, K. L., … Martin, S. S. (2022). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 145(8), e153–e639.

[17] Sabbatini, A. R., & Kararigas, G. (2020). Menopause-Related Estrogen Decrease and the Pathogenesis of HFpEF: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(9), 1074–1082.