Engineering Anti-Inflammatory Cells to Fight Arthritis

- Contained in a scaffold, these cells automatically fight inflammation.

Publishing in Science Advances, a team of researchers has described how a scaffold containing genetically engineered induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can reduce symptoms in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis.

The advantage over current drugs

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is currently treated through drugs that often suppress the immune system as a side effect [1]. Despite the fact that RA fluctuates over time, the drugs that are prescribed for it are normally given at a constant rate on a fixed schedule.

One known drug is IL1 receptor antagonist (IL1-Ra). As the researchers explain, this compound mitigates the disease in animals and slows joint damage in humans [2], but its moderate effects and rapid dissipation make it an uncommon choice for a prescribed pill [3]. These properties, however, made it an ideal choice for the researchers to use as the output of their CRISPR-engineered cells, which are designed to express it only in the presence of inflammation.

The process

Before attempting to develop the treatment itself, the researchers created a 3D scaffolding upon which their new cells could sit. Their next step was to develop cells that, upon detecting the inflammatory signal Ccl2, expressed luciferase, a harmless, light-emitting compound; these are Ccl2-Luc cells. This initial experiment showed clear results: the luciferase was visible when the inflammatory compound was present.

The researchers then developed cells that would express IL1-Ra upon detection of Ccl2, creating Ccl2-IL-1Ra cells. They used an identical scaffolding system to insert these cells into a group of mice, using the luciferase scaffolding for the control group.

The results

The results were clear, and the benefit of the scaffolding system was evident. Injecting the cells without scaffolding into wild-type mice with temporary arthritis yielded limited benefits that were not statistically significant, and the cells only lasted for 24 hours. However, cells contained within the scaffolding lasted for over 5 weeks in living mice, and the results of mice given the treatment scaffold were positive in multiple ways.

After being artificially given temporary arthritis through K/BxN serum administration, mice that had the treatment scaffold enjoyed higher pain thresholds and thicker ankles compared to the control group. The inflammatory index, a measurement of inflammation, was decreased by approximately 40%. Bone erosion, a common effect of arthritis, was decreased nearly to zero compared to the highly eroded control group.

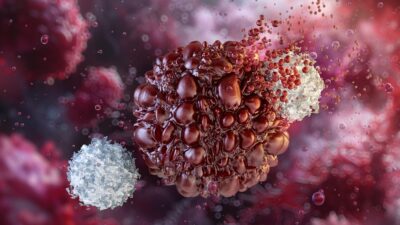

Most critically, the engineered Ccl2-IL-1Ra cells were shown to be working as intended: with the increased inflammatory IL1 came the anti-inflammatory IL1-Ra. From a pharmacological point of view, the drug was being administered automatically in response to the animals’ need for it.

The researchers tested their approach against the drugs that constitute the current standard of care, including tofactinib, methotrexate, and anakinra, and their scaffolding outperformed each of those drugs in mice.

Conclusion

As the researchers state, this engineered cell treatment isn’t just a potential treatment for arthritis: it is a proof of concept that this approach is valid for a wide variety of inflammatory diseases. If this approach can be further refined and developed to work in human beings, we might see a day in which many drugs are no longer administered as pills, instead being delivered by cells that automatically recognize the need for them within the body. We look forward to this approach being used to combat the age-related systematic inflammation known as inflammaging.

Literature

[1] Tarp, S., Eric Furst, D., Boers, M., Luta, G., Bliddal, H., Tarp, U., … & Christensen, R. (2017). Risk of serious adverse effects of biological and targeted drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review meta-analysis. Rheumatology, 56(3), 417-425.

[2] Bresnihan, B. (1999). Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 58(suppl 1), I96-I98.

[3] Abramson, S. B., & Amin, A. (2002). Blocking the effects of IL-1 in rheumatoid arthritis protects bone and cartilage. Rheumatology, 41(9), 972-980.