Exercise Intensity, Duration, and Amount All Matter

- Average exercise amount declines sharply with advanced age.

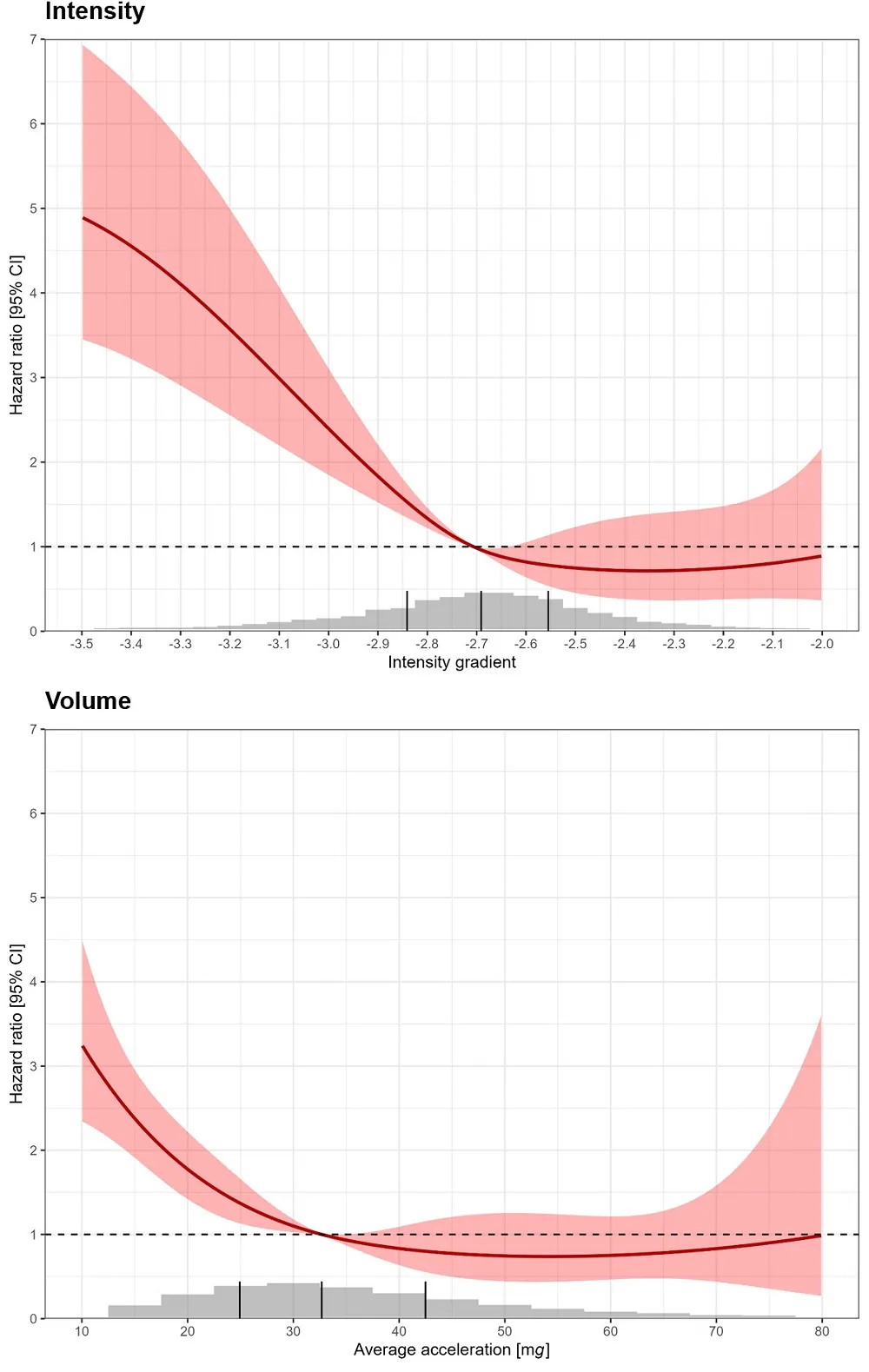

In the European Journal of Protective Cardiology, researchers have published evidence that the intensity of exercise is somewhat more important than volume in reducing all-cause mortality risk, although both have significant correlations.

The questions of how long and how much

Conventional wisdom had maintained that exercise must be conducted in continuous periods to be of value, but in some public health circles, there has been a shift away from this: the World Health Organization stopped recommending exercise periods to be for at least 10 minutes. Instead, the new paradigm is that “every minute counts” [1]. This shift is based on studies that have compared the effectiveness of different interval lengths of exercise [2].

However, interval duration is not the same as total amount (volume) or intensity. The volume of movement during the day has been documented to be related to mortality [3], and interval intensity has been investigated for issues such as bone health [4], but these researchers note a previous lack of cross-sectional studies that directly compare exercise intensity to volume and duration.

Intensity and consistency

Like many other cross-sectional studies done in the United States, this study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [5]. This study is largely reflective of the US adult population. The mean age of participants was 48, and the average BMI was 28.

To measure exercise, the participants each wore a wrist accelerometer for a week. The related metrics, therefore, were quantified in terms of acceleration: the total volume of exercise was listed as AvAcc, and intensity was measured as a gradient (IG). Making allowances for brief breaks, continuous activity was measured, as was the comparative ratio of the most intense to the least intense activity periods. While intensity had a stronger effect than volume, both volume and intensity had profound impacts on all-cause mortality: too much was not good, but less intensity, particularly for people who had less than the average 70-year-old, was strongly associated with a higher risk of death.

The effect of intensity was even stronger in the case of cardiovascular risk. AvAcc did not quite reach the level of statistical significance, but IG was found to have a similar curve to the all-cause mortality curve.

Fragmentation of exercise was found to be negative. People who moved in continuous 5-minute, 15-minute, or 60-minute bouts were less likely to die of any cause than people whose bursts were more sporadic. The researchers give as an example someone who briskly walks at random intervals for a total of 15 minutes during the day; if this person were to briskly walk for 15 minutes all at one time, that person would have a substantially reduced mortality risk.

Therefore, while every minute does count, it is still a good idea to have time set aside for steady amounts of relatively intense exercise. The researchers hold that their research differs from WHO’s recommendations due to their differences in data collection and handling techniques.

While this study’s modeling did account for chronological age when determining hazard ratios, the researchers also noted that older people are far less likely to be able to move as much as younger people, particularly people in their 80s and 90s. This was true for both men and women, and it was especially reflective of intensity even more than volume.

Limitations and concurrences

This study did have some limitations. Specifically, it was impossible for the researchers to adjust for smoking, mobility limitations, and alcohol use, due to a lack of data in any of these categories. It is also impossible in this sort of research to fully account for reverse causation: people who engage in less-intense exercise may be suffering from undiagnosed conditions that limit their ability to move as much. Deaths within the first 12 months were excluded from this study in order to mitigate this problem.

Despite its limitations, however, this study’s results are in close accordance with other work on the subject, including research that used UK Biobank data to determine that intensity is critical in maintaining health and fighting back against aspects of aging [6]. The researchers also note that their work concurs with research demonstrating that exercise that is intensive and long enough to make demands of the cardiovascular system is important for vascular and respiratory health [7]. While this is a populational study and cannot be directly applied to an individual, it is clear that sustained, intense exercise periods are directly correlated with a reduced risk of death.

Literature

[1] Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., … & Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British journal of sports medicine, 54(24), 1451-1462.

[2] Jakicic, J. M., Kraus, W. E., Powell, K. E., Campbell, W. W., Janz, K. F., Troiano, R. P., … & 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2019). Association between bout duration of physical activity and health: systematic review. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 51(6), 1213.

[3] Rowlands, A., Davies, M., Dempsey, P., Edwardson, C., Razieh, C., & Yates, T. (2021). Wrist-worn accelerometers: recommending~ 1.0 mg as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in daily average acceleration for inactive adults. British journal of sports medicine, 55(14), 814-815.

[4] Rowlands, A. V., Edwardson, C. L., Dawkins, N. P., Maylor, B. D., Metcalf, K. M., & Janz, K. F. (2020). Physical activity for bone health: how much and/or how hard?. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 52(11), 2331-2341.

[5] National Center for Health Statistics (US). (2013). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2007-2010. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service.

[6] Dempsey, P. C., Musicha, C., Rowlands, A. V., Davies, M., Khunti, K., Razieh, C., … & Samani, N. J. (2022). Investigation of a UK biobank cohort reveals causal associations of self-reported walking pace with telomere length. Communications Biology, 5(1), 381.

[7] Hov, H., Wang, E., Lim, Y. R., Trane, G., Hemmingsen, M., Hoff, J., & Helgerud, J. (2023). Aerobic high‐intensity intervals are superior to improve V̇O2max compared with sprint intervals in well‐trained men. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 33(2), 146-159.