Longevity in Centenarians Linked to Lower Ribosomal Activity

- Protein restriction may be similar to caloric restriction in extending lifespan.

Scientists have discovered a possible mechanism that protects extremely long-lived people from aging [1].

Protected persons

A few days ago, news came of the death of the oldest person in the world (and the oldest ever to have her age indisputably confirmed), 119-year-old Kane Tanaka from Japan. People who live past 100 or 110 years old do not achieve this by making extremely healthy lifestyle choices. Instead, they just seem to age more slowly, being protected from the diseases of aging by currently unknown natural mechanisms. Geroscientists, of course, are eager to study extremely long-lived individuals, hoping to uncover those mechanisms for the benefit of the rest of humanity (read our interview with Nir Barzilai, who has been studying supercentenarians for years).

In this new study, Chinese researchers obtained and analyzed the transcriptomes of white blood cells taken from 193 long-lived Chinese women (around 100 years old, active and living independently, which, according to the authors, indicates good chances of living past 110). As controls, the researchers used 86 other women with an average age of 57. Of course, there cannot be age-matched controls when studying centenarians: age itself is what determines a person’s place in either the study group or the control group.

Ribosomes and proteins

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that the genes related to lysosomal activity were significantly upregulated in the study group compared to the control group. This was hardly surprising, since lysosomes are organelles involved in autophagy – the process of breaking up and clearing intracellular waste. Increased autophagy has been linked to longevity in various model organisms [2].

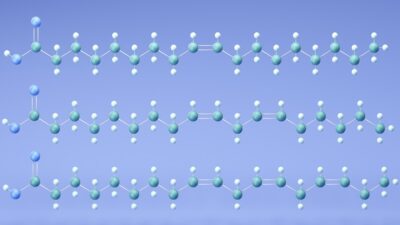

The main and more surprising finding of the study was the extremely significant downregulation of ribosome-related genes, especially ribosome protein genes (RPGs). Ribosomes are the organelles that produce proteins from amino acids according to the “blueprints” provided by messenger RNAs. If RPGs are downregulated in the cell, it produces fewer building blocks for ribosomes, hence fewer proteins.

The authors interpret this finding in the context of the hyperfunction theory of aging, which has been gaining popularity recently. This theory postulates that some bodily processes are optimized for growth and reproduction, which is all nature cares about. Protein production is one such process: it is indispensable for growth and development, but it also accelerates aging. Protein restriction effectively slows aging in model organisms and provides multiple health benefits in humans [3]. Importantly, protein restriction works at least in part by modulating the mTOR pathway [4], which is also what the well-studied geroprotective molecule rapamycin does.

As the controls were not age-matched, there is a possibility that this and other differences in gene expression can be attributed to natural aging rather than to centenarian-specific anti-aging mechanisms. To minimize this possibility, the researchers confirmed that in the control group, which was relatively heterogeneous in age, the levels of expression of both lysosome-related and ribosome-related genes were age-independent.

One factor to rule them all

Since ribosome-related genes are always co-expressed (their expression levels change simultaneously), the researchers looked for a transcription factor that might bind to the promoters of most of those genes, regulating their expression. The gene ETS1 fitted the profile, showing strong correlation with the ribosome-related genes.

To confirm ETS1’s role, the researchers created human embryonic kidney cells with the ETS1 gene knocked out. Transcriptomic analysis showed that the ribosome-related genes in these cells were significantly downregulated. This result was then reproduced in human dermal fibroblasts. Downregulation of ETS1 resulted in significantly less cellular senescence, as measured by the senescence markers ß-galactosidase, p-16, and p-21 and in increased cell proliferation. Interestingly, a recent study showed that knocking out drosophila’s homolog, ETS1, significantly increases lifespan in those animals. Taken together, these findings point to ETS1 as a potential therapeutic target.

Women only?

The researchers do not report why the study was female-only, but that might be a limitation of the particular dataset (large centenarian transcriptome datasets are hard to come by). However, this issue can be very consequential, since there is a growing understanding that some aging mechanisms are sex-specific, as evidenced by the fact that most compounds found by the ITP (Intervention Testing Program) to prolong lifespan in mice disproportionately benefit one sex.

Conclusion

Studying extremely long-lived humans can provide valuable insights into the very nature of aging. According to this new study, centenarians (at least women) might possess a mechanism that dampens protein production by reducing the activity of ribosome-related genes. This is mostly in line with previous research in model animals and humans. It remains to be seen whether this mechanism is sex-specific and to what extent.

Literature

[1] Xiao, F. H., Yu, Q., Deng, Z. L., Yang, K., Ye, Y., Ge, M. X., … & Kong, Q. P. (2022). ETS1 acts as a regulator of human healthy aging via decreasing ribosomal activity. Science Advances, 8(17), eabf2017.

[2] Hansen, M., Rubinsztein, D. C., & Walker, D. W. (2018). Autophagy as a promoter of longevity: insights from model organisms. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 19(9), 579-593.

[3] Mirzaei, H., Raynes, R., & Longo, V. D. (2016). The Conserved Role for Protein Restriction During Aging and Disease. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 19(1), 74.

[4] Hill, C. M., & Kaeberlein, M. (2021). Anti-ageing effects of protein restriction unpacked.