Michael Geer: “Digital Markers Are the Future”

- His company, Humanity, focuses on improving healthspan and lifespan through data.

Michael Geer is a successful serial entrepreneur who came to the longevity field to get things going. He and his co-founder Pete Ward have recently launched the app Humanity, which offers its users ways to monitor their rates of aging and makes actionable suggestions as to how to slow those rates down. We talked to Michael about why apps like this are important and went into the details of how Humanity works.

The market for consumer-oriented aging biomarkers is exploding. What is their importance not just to Humanity with a capital H but to humanity and to the longevity field?

Basically, people want to be healthier for longer. They want to be fully functional, disease-free – or as disease-free as possible for as long as possible. So, they want to have feedback that would tell them whether they are heading in a better direction or in a reverse direction.

But is it working? The fitness industry sells a lot of flashy things that do have some relation to health, but they don’t necessarily tell you whether you’re going to be healthier in the future. This is why people are so interested in a holistic measure of future health, that’s why what we’re doing is so attractive.

Do you feel like this is new to most people, this mindset of thinking of aging as something that can be slowed or reversed?

The words may be different, but I guess what many people think about health is that they generally want to keep being the way they are now, keep functional, keep doing all those things they like. It’s a simple thought that means staying mobile, not having a disease. Now, it may be framed as aging, which sounds a bit new conceptually, but it’s mostly the label that changed.

On the other hand, the understanding that their body is slowly losing function, moving towards greater susceptibility to disease – that’s something new. The way that most people, including doctors, still talk about health is somewhat binary: you either have a disease or you don’t. This concept that you’re gradually moving towards a higher susceptibility to disease is new and quite powerful because this leads to the question, what do you do now? How do you decrease the speed of this sliding towards greater susceptibility to disease? This is a call for action.

You are one of the cohort of passionate entrepreneurs who have discovered the longevity field and are moving it forward. How did you become involved?

In a past life, I was on the founding team of Badoo, a dating site. Around the time I left Badoo, a couple of people close to me got a late-stage cancer diagnosis and both passed away fairly soon after those diagnoses. From that moment, my biggest question was, why aren’t we screening everybody for cancer? Why are people finding out at stage four? I asked a bunch of doctors, and tons of different answers were given, as you can imagine.

The main answer, which made sense, was there’s too many false positives. If you screened everybody for cancer, no matter their age or family history, you would end up with telling many people that they might have cancer when they don’t, and you might end up subjecting them to unnecessary, dangerous procedures.

This did seem like a logical answer. I reached out to a few people asking “How do we take the false positives out of these tests?” The answer at the time (which is actually coming to fruition with a few companies now) was to use genetic sequencing [cancer tests based on circulating DNA].

Being of the founder mentality, I just Googled top people in genetics. Two names come up when you do that, or at least back then, this was the case: Craig Venter and George Church. I reached out to George, and he was very kind to spend some time with me. He answered a lot of my questions, which were, I’m sure, very stupid at the time and hopefully are slightly less stupid now.

I started talking to George, and then I moved out to the Valley to help run a consumer VPN company. When I was out there, I began talking to people at UCSF [University of California – San Francisco]. Then serendipitously, through some events, I also met people from Buck Institute.

All those people – stem cell researchers, immunologists, geneticists – were spending a lot of time in their labs trying to measure the loss of function in the systems they were looking at. That really intrigued me because I had never had that concept before. This is how we started our conversation today – that concept of our systems losing function gradually, over a long period of time, and that it can be measured. In all those labs, scientists are trying to measure this because they need to test new compounds, they need a way to know if the compound actually decreases the loss of function in the system, because that’s the goal.

You mean, we need biomarkers of aging.

Yes. And then I was lucky enough to get connected with Kristen Fortney [CEO of BioAge Labs], and she turned me onto this idea that you could go to the biobanks, to these longitudinal data sets and see the biomarkers in the past, and also the future real health outcomes.

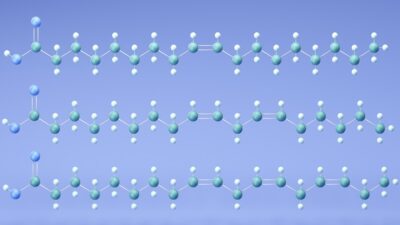

A few minutes after that conversation, I began thinking that we definitely need to bring this to consumers if we can, and it sounded like since there are digital markers in some of those biobanks; you could actually do that as opposed to having to test everybody’s blood.

Then I pulled my co-founder, Pete Ward, who has a similar background (he created one of the first popular social networks), and we started looking into it. We went to what we called science fantasy camps. We’d fly into Boston; we’d do our whole genome, but the real reason we were there was because we wanted to meet up with George again and other people in that space. So, that’s what we did. I was a believer after spending enough time just sitting in people’s labs, and Pete also was in enough meetings to become a believer too. The rest is history.

Can you give me your elevator pitch for Humanity?

Humanity is an app that can tell you how fast you’re aging and then, importantly, can guide you towards the actions that will slow down your aging. Our focus is on answering the two questions that everybody has about health. First, what should I be doing to be healthier? And the second question is, how do I know when it’s working? Humanity is set up to answer those two questions. Our laser focus is to help people to know what they can do to slow their aging, and then be able to see whether the thing that they’re trying is actually working.

What is your business model – subscription-based, selling data, or something else?

Definitely not selling data. Yes, it’s freemium subscription. The whole business model is based on subscription. Freemium is a great model because it means 95% of your users are getting a ton of value for free, and then the 5% that want the premium features upgrade, and that makes the whole business run. It’s a surprisingly good model because it lets you make the impact that you want. We want to be as radically inclusive and impactful as possible, and this can only be done if most of the service is free or semi-free.

When up to 95% of your users are using it for free, and you still have a great viable business, that’s what you aim for. There will be other things – upsells, different tests, et cetera, but the mainstay will always be those different subscription levels. There’s a digital subscription that we already have, and then there’ll be a higher subscription, which will allow you to do things like DNA methylation testing.

Hopefully, soon you will be sitting on a mountain of data, which will be your significant competitive advantage. On the other hand, you want to make this data widely available. How do you plan to strike the balance here?

We’ve created and sold a couple of companies at this point. Our balance is far pushed to the impact side. We want to be, and we already are, very open and collaborative. We want our impact to not just be within the walls of the app. We want to help the entire space, to learn more and be able to do more. A part of that is getting the learnings from the data out to others.

There are a few different ways we can do that effectively at scale. One of the most interesting ways that I’m looking quite a bit at is federated learning. Basically, this means the data stays where it is. Wherever the user put the data, it stays there.

Then machine learning algorithms come down into these siloed data sets, do some kind of learning, but then they only take the gradient change of those learnings out. And you have a privacy layer that checks to make sure that there’s no way to reverse engineer back to the actual data.

That’s done at scale by companies like Google. They do it for their predictive texts on Android phones. That’s one way to cooperate, and the beauty of that is that the user always has full control over their data.

When you actually anonymize data, the user loses a bit of control, because even though people would say that the data can’t be tracked back to the user, it’s still their data and it’s still out there. With federated learning, it’s a better system. If the user wants us to delete all their data, Humanity has this ability.

Let’s dive deeper into the app. It takes in an impressive variety of metrics: physical activity, stress levels, nutrition, sleep quality, et cetera, and it returns a single biological age score. How is it calculated? What’s the science behind it?

There are two main algorithms that the user data is feeding. On the first side, you have a health navigation system. It’s seeing all the actions that a certain type of person is taking and how it’s affecting their rate of aging. Many of those things are being collected so that we can then suggest to that user and to other users different combinations of actions because they seem to be the ones that lead to the path to better health.

On the second, the rate of aging side, two main things are going into that. You’ve got the movement patterns. Basically, it’s accelerometer data from the phone and/or wearable that shows your movement patterns throughout the day. If you have a wearable, there’s also the heart rate. We are then calibrating with other predictors that can be found in our data and the external longitudinal datasets, including chronological age, gender, wearable sensor types, etc.

A lot of this data comes from the UK Biobank right now, but we will expand out from there. In this external dataset, we have people who have been monitored for 10, 15, 20 years. In the UK Biobank dataset, in addition to biomarkers, they also put accelerometers on a ton of people and recorded continuous heart rates from a bunch of people in the past.

And then, in the future, in the next 10 years or so, scientists follow up and collect all the health data, all the health events that happen to those people. One person had a heart attack. Another one got diagnosed with this or that type of cancer. Any morbidities, and in some cases, unfortunately, mortalities, get recorded. With the longitudinal data set like that, you’re able to get a signature: what does a person who’s going to have a heart attack in 10 years, or who’s going to be diagnosed with cancer, look like.

Then we can go to our internal user base and gather those same markers on the digital side – the movement patterns, the heart rate, and we can compare those signatures. This is how we build the probabilistic health trajectory of every person.

In our case, we’re working with a great partner, Gero. It provides a significant portion of that digital side that comes into our model. And then we do more internal calibration. First, calibration within devices because Fitbits and Apple watches and everything else are not created equal. We also do some other calibrations. I won’t go into all the details, but that’s why we believe that the accuracy is as high as possible.

Still, non-invasive biomarkers of aging, like those based on movement, are unorthodox.

I’ll get a little bit deeper into the logistics side of it. There’s a lot of variance in blood markers, and these markers are usually only measured once or twice a year. But with movement, you have continuous monitoring.

So, even if the blood markers measure the state of the body better, which I don’t think is actually the case, I would say it is still outweighed or at least counterbalanced by the frequency of the measurement of the digital markers. I think there’s a lot of obvious reasons to say that digital markers will be the future.

I’m acquainted with Gero’s concept, and I agree with you about its benefits. Still, it’s not exactly proven yet. Which means you’re basically building a biological age clock on the go, training your models on users’ data, is that correct?

We will definitely do that, but the most important thing you need in order to improve upon the model is to get real health outcomes. So, I think the bigger thing we’ll do in the next year is to expand the external datasets that we’re training our models on.

As you move forward one year, two years, three years, and you get more access (which is actually happening quite nicely, as Apple and others are making it easier for the electronic health records to be connected up), as the users opt in to give you access to their data, you can definitely start using your internal data to make the models even better.

Having access to the actual health outcomes of the users does seem crucial.

It’s crucial to have that in the external dataset. It’s not as crucial to have it on the internal users, but it will make things more accurate when we do it, sure.

Has your clock been tested against existing biological age clocks?

We have stacked it up against some other clocks. We haven’t released any numbers though. Importantly, the stance that we’ve taken is collaboration. I think that ‘the clock to win them all’ is not going to get anybody anywhere. We’d like to be very open and transparent about it. Let’s openly talk about clocks’ strengths, their weaknesses, and how can we make them better. We’re very interested in that conversation, and we’re already having it.

Through marketing pressures, sometimes people are pushed into saying that theirs is the best measure, but I think, if we’re all honest with each other, all the clocks have their strengths and weaknesses. So how can we help? How we can put them together so that we get the best coverage of predictiveness? This is the question.

Let’s go back to the app. After several decades, the longevity field still doesn’t have a magic pill. The best interventions that we have are the good old stuff like physical activity and a healthy diet. Do your recommendations to people consist mainly of that?

Yes, right now, the guidance is very much lifestyle actions. I think it will continue to be that way for some time. Supplements will also be part of the guidance. The beauty of this is that if and when new, better things emerge, such as better senolytics, we’ll be poised to allow people to try that as well, and, importantly, people will be monitoring themselves with the app to actually know if it’s working or not.

I think we’re talking about 20, 30 years of healthy life that people can add with lifestyle actions and maybe some supplementation, and that’s our goal. Then, hopefully, more things will continue to come through. We’re super excited about all the stuff that David Sinclair and other people are working on. We’re rooting for them, but there are things people can do right now to add decades to their lives. That’s our current focus.

You and I know how important these lifestyle interventions are for longevity, but from the consumer’s point of view, do you think it might be just a little bit underwhelming – “these guys say that they can slow my rate of aging, but what they’ve been telling me is actually what my Apple watch tells me every day”?

To be very honest with you, the mainstream consumer loves it. For a biohacker, there is probably a little bit of that thought. “I have all my charts and all my measures, and they’re just telling me all those usual things.” But as a company, because we’re a startup, we need to concentrate on helping the majority of people.

Biohackers might feel the need to supplement our app with other stuff they’re doing, but from our 25 thousand users, we already see that they actually are engaging and changing their behavior quite a bit. At least for the mainstream user, it’s already quite enough.

We built this thing so we could start slowing down people’s aging immediately. I think the longevity field needs more of that because there’s a lot of drug discovery going on, but the timelines there are long. Meanwhile, we need to be extending people’s healthspan and lifespan now.

To which camp do you belong in terms of longevity – meaning, are you a fan of extreme life extension, or do you think it’s unrealistic or even not the best thing to pursue?

I’m a very big believer in the idea that we create the world around us. I think it’s quite apparent that there are things we can do to greatly lengthen our healthy lives.

We launched Humanity to start proving to people that, first, they are aging at different rates, and second, that there are things they can do right now to change that rate. In the long term, physically or scientifically, I don’t see anything that says that we couldn’t greatly extend human lifespan.

I’m in camp “everybody should have a choice”. I want to have a choice of when to die, and I think many people would like to have that choice too. And, scientifically, we will probably have the ability to allow that choice if someone is like: “Hey, I want another 50 years.”