New Combination Therapy Eradicates Cancer in Mice

- Senescent cancer cells convince the immune system not to attack.

Scientists have discovered a mechanism that lets senescent tumor cells undermine chemotherapy. With this mechanism blocked, standard chemotherapy led to complete regression of mammary tumors in mice [1].

Senescent yet still dangerous

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, still the two most common treatments for solid tumors, subject cells to powerful stress as they are designed to do. This stress drives cellular senescence. Since senescent cells stop proliferating, inducing senescence in cancer cells is considered a desirable outcome. However, this is not the end of the story.

Despite not being able to proliferate, senescent cancer cells are still capable of obstructing efforts to eradicate the cancer completely. First, they secrete the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a complex mixture of various molecules, some of which interfere with anti-cancer immune responses. Second, they express PD-L1, a surface protein that tricks immune cells into thinking they’ve encountered a bunch of normal, law-abiding cells rather than a malignant tumor. A new study published in Nature Cancer, with a list of authors that includes the prominent geroscientists Manuel Cerrano and James Kirkland, uncovered yet another such mechanism.

Senescent cancer cells express PD-L2

To investigate the behavior of senescent cancer cells, the researchers induced senescence in human melanoma cells via chemotherapy. Their interest was then triggered by the notable senescent cell upregulation of PD-L2, another molecule that, just like PD-L1, binds to the checkpoint protein PD-1 on the surface of immune cells, dampening their cytotoxic response. While PD-L1 is more well-known in the context of immunotherapy, since it is expressed abundantly in tumors, it’s the rarer PD-L2 that binds PD-1 several times more potently. The researchers observed similar senescence-related PD-L2 upregulation in several other cancer cell lines, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma and osteosarcoma.

To investigate this intriguing phenomenon further, the researchers created mouse pancreatic cancer cells with PD-L2 knocked out using CRISPR. Immunocompetent mice were injected with either those PD-L2 KO cells or wild-type pancreatic cancer cells. Then, both groups of mice were subjected to chemotherapy with doxorubicin, which controlled the growth of PD-L2 KO tumors much better, increasing survival.

Was this discrepancy in response to chemotherapy due to a difference in immune reaction? When the same two types of cancerous cells were injected into immunocompromised mice that lacked T cells, no differences in tumor growth either before or after chemotherapy were recorded. Clearly, the adaptive immune system was responsible for the better outcome in PD-L2 KO mice, specifically, CD8+ T cells, as the researchers were able to show. Those cells are cytotoxic: that is, they directly kill unwanted cells, as opposed to “helper” T cells which orchestrate the immune response while staying away from the front lines.

Stripping protection from senescent tumor cells

Knocking out PD-L2 worked by neutralizing one of the many tricks used by cancer cells. Tumors produce signaling molecules that attract myeloid cells, which are immune cells that originate in bone marrow, such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Once recruited to the tumor, myeloid cells often undergo functional changes due to the local tumor environment [2]. For instance, tumor-associated macrophages can switch to a phenotype that promotes tumor growth.

The researchers observed increased recruitment following chemotherapy of some myeloid cells in wild-type tumors, but not in PD-L2 KO tumors. Depletion of CD8+ T cells restored myeloid cell recruitment in PD-L2 KO mice. According to the researchers, when senescent tumor cells are protected from CD8+ T cells by PD-L2, they successfully recruit myeloid cells, which impair the anti-tumor immune response. Without PD-L2, T cells quickly eliminate the senescent cells, preventing myeloid cell recruitment and improving the results of chemotherapy.

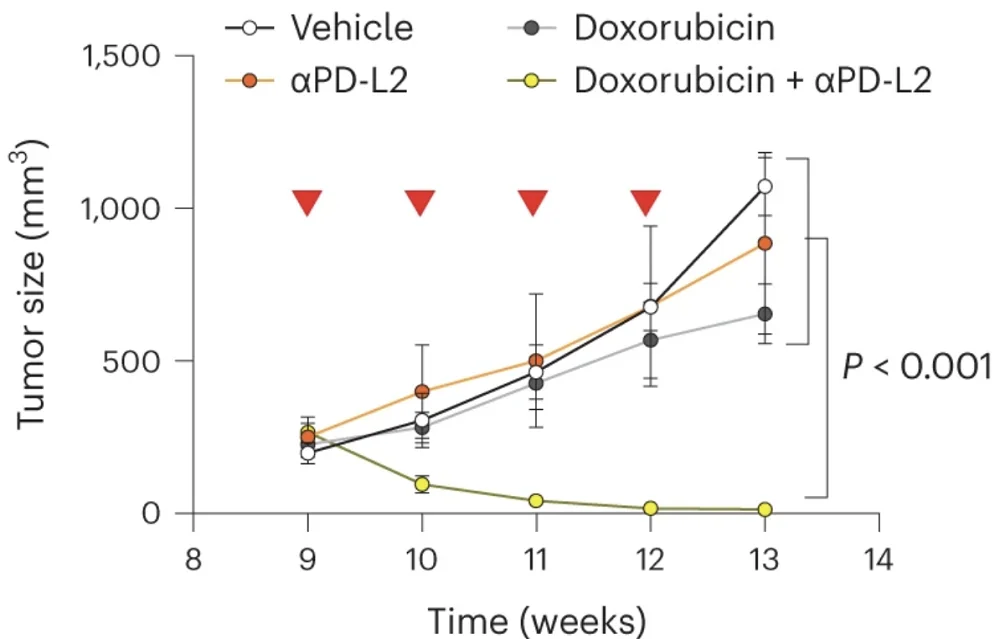

Capitalizing on this insight, the researchers tested a combination therapy in a mouse model of breast cancer. Individually, chemotherapy or PD-L2-blocking antibodies had only mild effects on tumor growth, but combined, they led to complete tumor regression in all animals. These results are supported by previous research that has shown the synergistic effect of senolytics and chemotherapy [3], and they might soon lead to the creation of new, more effective anti-cancer treatments.

In this study, we demonstrate that senescence-inducing therapies used in the clinic result in the upregulation of PD-L2 in cancer cells. While the expression of PD-L2 is not necessary for senescence induction or for the secretory phenotype of senescent cells, it critically contributes to the immune evasion of cancer senescent cells in tumors after therapy in vivo. Intratumoral senescent cancer cells do not proliferate but, as we report in this study, favor cancer regrowth after therapy thanks to their immunosuppressive effects.

Literature

[1] Chaib, S., López-Domínguez, J. A., Lalinde-Gutiérrez, M., Prats, N., Marin, I., Boix, O., … & Serrano, M. (2024). The efficacy of chemotherapy is limited by intratumoral senescent cells expressing PD-L2. Nature Cancer, 1-15.

[2] Schouppe, E., De Baetselier, P., Van Ginderachter, J. A., & Sarukhan, A. (2012). Instruction of myeloid cells by the tumor microenvironment: open questions on the dynamics and plasticity of different tumor-associated myeloid cell populations. Oncoimmunology, 1(7), 1135-1145.

[3] Wang, L., Lankhorst, L., & Bernards, R. (2022). Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 22(6), 340-355.