A Protein That Exacerbates Heart Disease With Age

- This protein only had effects in older animals.

- In older male mice, administering Hevin worsened age-related heart dysfunction by increasing inflammatory macrophage activity.

- Reducing Hevin or blocking its downstream pathways ameliorated this dysfunction.

Researchers publishing in Aging Cell have found that Hevin, a protein found in the extracellular matrix that increases with age, leads to heart problems in older male mice.

Inflammaging contributes to heart disease

Read More

The researchers begin by outlining the mechanisms involved in inflammaging, noting how it is closely connected to various progressive problems in the heart, leading to its gradual loss of function [1, 2]. Unsurprisingly, suppressing inflammatory cytokines led to better cardiac outcomes in mice [3], and prolonging lifespan by preventing inflammaging-related heart disease has been a biotechnology goal for some time.

Macrophage behavior is a key part of this relationship. Pro-inflammatory M1-polarized macrophages are good at killing off pathogens, but they cause damage to surrounding tissues; M2-polarized macrophages reverse this process and repair tissues. Aging drives a shift from M2 to M1 behavior [4], and one of the main chemical culprits is CCL5, a ligand that impedes the polarization of macrophages towards M2 [5].

Hevin, which is found in the extracellular matrix, plays a variety of roles in disease. We have previously reported that Hevin has significant benefits against brain aging in mice, but other work has found entirely different functions, including activity against cancer by recruiting macrophages [6]; however, the recruitment is of M1 macrophages, potentially worsening diseases such as pneumonia [7] and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [8].

Hevin is hell for older animals

Unsurprisingly, Hevin in the plasma increases with age in people, particularly in people over 60 [9]. In line with previous work finding it to be a biomarker of heart failure [10], these researchers found that it is associated with a decrease in ejection fraction.

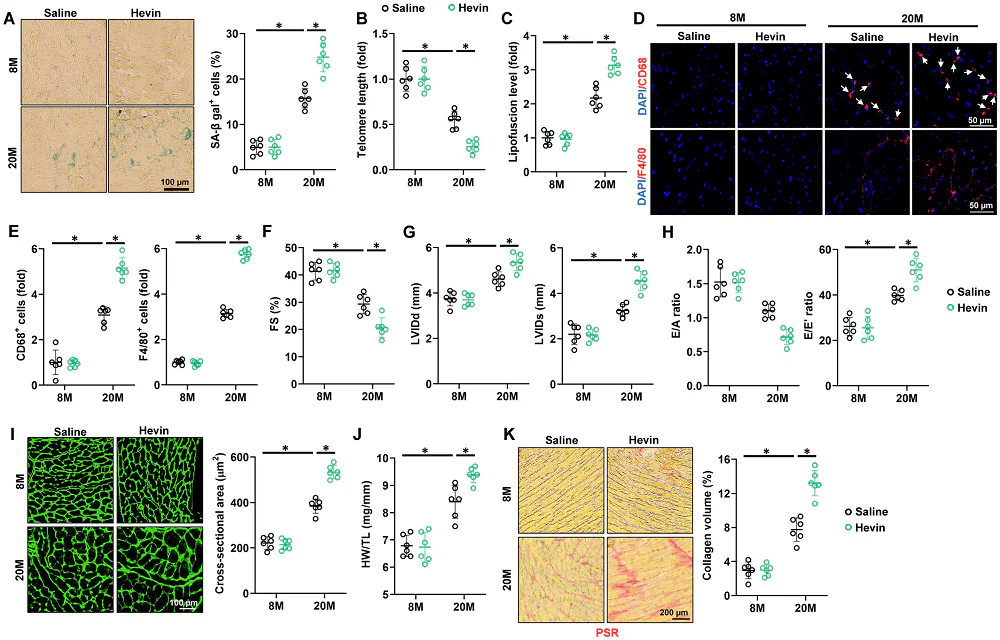

In mice, Hevin expression does not increase in the heart; rather, it increases in fatty tissues and is then distributed throughout the body, and this increase in Hevin distribution is accompanied by a decrease in the heart’s ability to effectively pump blood. Directly introducing Hevin to 20-month-old mice did not change blood pressure nor heart rate, but it promoted cellular senescence and shortened telomeres in the heart, increased macrophage infiltration along with inflammatory cytokines in cardiac tissue, and increased fibrosis and hypertrophy while contributing to the heart weakening already seen in older mice. However, these negative effects were only seen in older animals; injecting 8-month-old mice with Hevin caused none of these problems.

The researchers then used an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to knock down Hevin. Just like with introducing Hevin itself, this treatment had no effects on younger animals; however, in the 20-month-old mice, many age-related diseases were ameliorated by this treatment. Senescent cell biomarkers decreased, telomeres were lengthened, hypertrophy was diminished, and both hypertrophy and fibrosis were significantly decreased.

Inflammation plays a key role

These effects were found to be largely due to Hevin’s effects on CCL5 in particular, as it significantly promotes the expression of this ligand and CCL5 was indeed found to promote M1 macrophage polarization in the heart. Older mice that were also treated with an anti-CCL5 antibody were partially spared from the inflammatory effects of Hevin injection, and this antibody also partially reversed the associated hypertrophy and fibrosis. Blocking toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and its associated p65 pathway had similar effects.

This study had certain limitations. While Hevin expression has sex-related differences in people, only male mice were used in this study, and further work will have to discover its effects on females. While the researchers surmise that Hevin has an amplifying effect on existing age-related processes, precisely why it had no effects on younger animals was not thoroughly investigated.

The connection between Hevin and fat was noted, and the authors suggest that reducing adipose tissue, such as through semaglutide, may be effective against its age-related increase. This, however, remains an open question as well. As Hevin is known to have beneficial effects in other contexts, whether or not it is wise to target it directly or indirectly is still a topic that requires more detailed investigation.

Literature

[1] Liberale, L., Badimon, L., Montecucco, F., Lüscher, T. F., Libby, P., & Camici, G. G. (2022). Inflammation, aging, and cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(8), 837-847.

[2] Liberale, L., Montecucco, F., Tardif, J. C., Libby, P., & Camici, G. G. (2020). Inflamm-ageing: the role of inflammation in age-dependent cardiovascular disease. European heart journal, 41(31), 2974-2982.

[3] Hu, C., Zhang, X., Hu, M., Teng, T., Yuan, Y. P., Song, P., … & Tang, Q. Z. (2022). Fibronectin type III domain‐containing 5 improves aging‐related cardiac dysfunction in mice. Aging Cell, 21(3), e13556.

[4] Becker, L., Nguyen, L., Gill, J., Kulkarni, S., Pasricha, P. J., & Habtezion, A. (2018). Age-dependent shift in macrophage polarisation causes inflammation-mediated degeneration of enteric nervous system. Gut, 67(5), 827-836.

[5] Li, M., Sun, X., Zhao, J., Xia, L., Li, J., Xu, M., … & Xia, Q. (2020). CCL5 deficiency promotes liver repair by improving inflammation resolution and liver regeneration through M2 macrophage polarization. Cellular & molecular immunology, 17(7), 753-764.

[6 Zhao, S. J., Jiang, Y. Q., Xu, N. W., Li, Q., Zhang, Q., Wang, S. Y., … & Zhang, Z. G. (2018). SPARCL1 suppresses osteosarcoma metastasis and recruits macrophages by activation of canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling through stabilization of the WNT–receptor complex. Oncogene, 37(8), 1049-1061.

[7] Zhao, G., Gentile, M. E., Xue, L., Cosgriff, C. V., Weiner, A. I., Adams-Tzivelekidis, S., … & Vaughan, A. E. (2024). Vascular endothelial-derived SPARCL1 exacerbates viral pneumonia through pro-inflammatory macrophage activation. Nature Communications, 15(1), 4235.

[8] Liu, B., Xiang, L., Ji, J., Liu, W., Chen, Y., Xia, M., … & Lu, Y. (2021). Sparcl1 promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression in mice through upregulation of CCL2. The Journal of clinical investigation, 131(20).

[9] Lehallier, B., Gate, D., Schaum, N., Nanasi, T., Lee, S. E., Yousef, H., … & Wyss-Coray, T. (2019). Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan. Nature medicine, 25(12), 1843-1850.

[10] Di Salvo, T. G., Yang, K. C., Brittain, E., Absi, T., Maltais, S., & Hemnes, A. (2015). Right ventricular myocardial biomarkers in human heart failure. Journal of cardiac failure, 21(5), 398-411.