Interrupting Sitting with Activity Lowers Glucose Levels

- Some exercises have stronger effects than others.

Scientists have discovered that frequently interrupting prolonged sitting with physical activity, such as short walks or squats, can help control glucose levels in overweight and obese males [1].

Don’t just sit there!

Prolonged sitting is the curse of modern times. It has been associated with various health problems, such as diabetes, poor heart health, weight gain, depression, dementia, and cancer. In overweight and obese people, sedentary lifestyle prevents calorie burning. It is a well-known recommendation to interrupt prolonged sitting with bouts of physical activity [2], but the actual effects of type, duration, and intensity of exercise remain an open question, especially in young individuals.

In this study by Finnish and Chinese scientists, the authors analyzed the effects of various kinds of sitting-interrupting activity in overweight and obese men. While various types of exercise can differ in energy expenditure, in this study, experiments were intentionally isocaloric – that is, involving similar caloric expenditure. The specific outcome the researchers monitored was the dynamic of glucose levels (glycemic control), which is something many obese people struggle with. Failing to maintain glycemic control can quickly lead to diabetes.

The study was relatively small, with 18 participants in total, but it had an interesting design. Each participant performed four different experiments with a seven-day washout period between them. Diets were standardized during the whole study.

SIT, ONE, WALK, SQUAT

The first experiment involved sitting for 8.5 hours. The participants were allowed to use their computers or read. The resulting average energy expenditure was 1,014.6 kcal. Standardized bathroom breaks were arranged and accounted for so that they did not contaminate the results. In their paper. The researchers dubbed this setting SIT.

In the second experiment, dubbed ONE, the sitting was only interrupted once after one hour by a 30-minute-long walk on a treadmill at 4 km (2.5 miles) per hour. In the third experiment, WALK, there were 10 interruptions, each one involving a short 3-minute walk. In both ONE and WALK, the average energy expenditure was measured at 1,123 kcal. Finally, the fourth setting was called SQUAT and, as you probably guessed, involved squatting: ten 3-minute-long interruptions in total, with the average energy expenditure of 1,120 kcal.

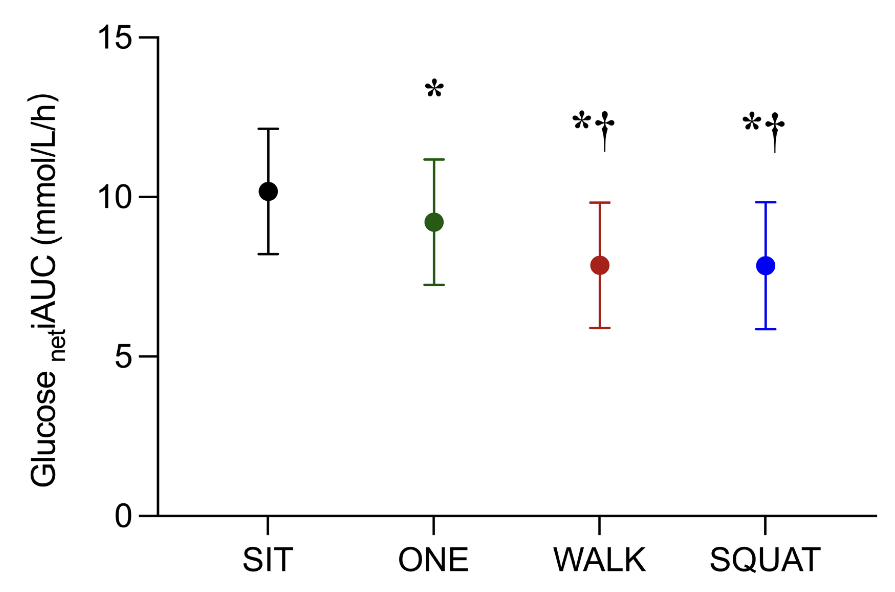

ONE resulted in a significant improvement in glucose control, reaching an AUC (area under curve) of 9.2 mmol/L/hour as opposed to 10.2 in SIT. More interestingly, the two other types of activity brought about an even more substantial improvement in glucose control (7.9 mmol/L/hour for both WALK and SQUAT).

Muscle activation matters

Why were WALK and SQUAT twice as effective in lowering glucose levels as ONE despite equaling it in energy expenditure? The researchers might have an answer. In addition to CGMs (continuous glucose monitors) and accelerometers, the participants wore special shorts laced with electrodes, enabling the scientists to perform EMG (electromyography) on various groups of muscles. WALK and SQUAT showed a much stronger signal of acute dynamic muscle activation, albeit in different muscles (quadriceps and glutes, respectively).

“Our data,” the authors conclude, “suggests that frequent interruptions to prolonged sitting, as opposed to a single bout of activity, are more effective in enhancing aEMG (average EMG amplitude) in the specific muscle groups engaged in the interruption activity, leading to a more favorable glycemic response.”

Further analyzing their data, the researchers found that activity duration was not associated with the efficacy of glycemic control. Previous studies suggest a possible explanation. When active, muscles uptake glucose, but only up to a certain threshold [3]. “Muscle cells,” the researchers write, “may reach their maximum capacity for glucose uptake within a defined timeframe, rendering additional muscle activity less effective in further lowering glucose response.”

To put things into perspective, the attenuation of glucose levels achieved during the experiments was not drastic, but it nevertheless might be helpful for trying to keep glucose in check. This research adds yet another good reason to frequently interrupt prolonged sitting with physical activity. Another recent study found that even 1- or 2-minute bouts of activity were associated with reduced mortality risk.

Sedentary behavior has become a significant global public health concern, with interrupting prolonged sitting being recognized as an effective strategy for promoting health. Recent research suggests that frequent, brief bouts of physical activity are more beneficial than longer, less frequent interruptions in improving glycemic control. By examining muscle activity patterns during interruptions, our study offers a promising physiological explanation for the effectiveness of frequent interruptions in managing glucose responses. Importantly, we found that increased intensity of lower limb muscle activation during multiple breaks leads to a more significant reduction in glucose response compared to a single break. This insight sheds light on the importance of elevated muscle activity, particularly during frequent sit-to-activity transitions, as a potential mechanism for improved glycemic control when interrupting prolonged sitting. It provides valuable guidance for designing intervention strategies aimed at promoting health through increased muscle activity.

Literature

[1] Gao, Y., Li, Q. Y., Finni, T., & Pesola, A. J. (2024). Enhanced muscle activity during interrupted sitting improves glycemic control in overweight and obese men. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 34(4), e14628.

[2] Hwang, C. L., Chen, S. H., Chou, C. H., Grigoriadis, G., Liao, T. C., Fancher, I. S., … & Phillips, S. A. (2022). The physiological benefits of sitting less and moving more: opportunities for future research. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 73, 61-66.

[3] Brewer, P. D., Habtemichael, E. N., Romenskaia, I., Mastick, C. C., & Coster, A. C. (2014). Insulin-regulated Glut4 translocation: membrane protein trafficking with six distinctive steps. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(25), 17280-17298.