The Future of Pensions and Life Extension

If you work in social security, it’s possible that your nightmares are full of undying elderly people who keep knocking on your door for pensions that you have no way of paying out. Tossing and turning in your bed, you beg for mercy, explaining that there’s just too many old people who need pensions and not enough young people who could cover for it with their contributions; the money’s just not there to sustain a social security system that, when it was conceived in the mid-1930s, didn’t expect that many people would ever make it into their 80s and 90s. Your oneiric persecutors won’t listen: they gave the country the best years of their lives, and now it’s time for the country to pay them their due.

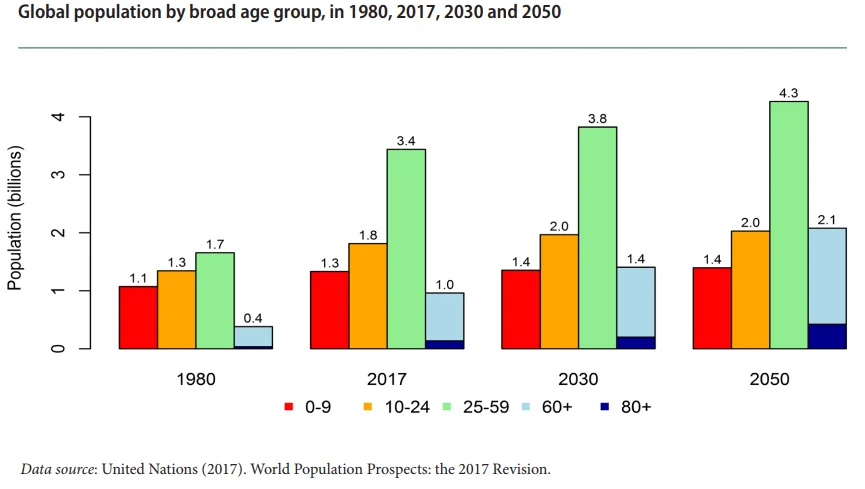

When you wake up, you’re relieved to realize that there can’t be any such thing as people who have ever-worsening degenerative diseases yet never die from them, but that doesn’t make your problem all that better; you still have quite a few old people, living longer than the pension system had anticipated, to pay pensions to, and the bad news is that in as little as about 30 years, the number of 65+ people worldwide will skyrocket to around 2.1 billion, growing faster than all younger groups put together [1]. Where in the world is your institution going to find the budget?

That’s why, whether you work in social security or not, the words “life extension” might make you feel like you were listening to an orchestra playing Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with forks on a blackboard; we’re likely to have a pension crisis on our hands as it is because of the growth in life expectancy, and some people have the effrontery to suggest that we should make life even longer?!

Why, yes, some people do have the effrontery, and believe it or not, it may actually be a good idea—possibly, and only apparently counterintuitively, the idea that will prevent the pension crisis from happening in the first place.

Why retirement?

Suppose for a moment that human aging never existed and that, barring accidents and communicable diseases, people went on living for centuries—their health, independence, and most importantly, ability to work, remaining pretty much constant over time; in order to tell apart a 150-year-old from a 25-year-old, you’d have to look at their papers.

In a scenario like this, it’s difficult to imagine why any government would go through the trouble of setting up a pension system that works the way the current one does. It would make sense to have measures in place to support people who couldn’t work after being paralyzed by injuries, but paying out money to perfectly able-bodied people to do nothing for the rest of their lives just because they’re over 65 would make no sense at all. It’s surely possible that, after 40 years of work, you’d rather be on vacation forever, but it’s somewhat unrealistic to expect that your country would be prepared to pay you a pension for centuries to come, in exchange for a meager 40 years of contributions, simply because you’re tired of working.

In other words, if people past a certain age have a right to retire until death and receive a pension, it’s essentially because, past that certain age, their health tends to worsen to the point that they’re unfit for work, and it can be expected to worsen in the following years; it’s not because the government or insurance companies feel like sending people on indefinite paid vacations. Depressing, perhaps, but true.

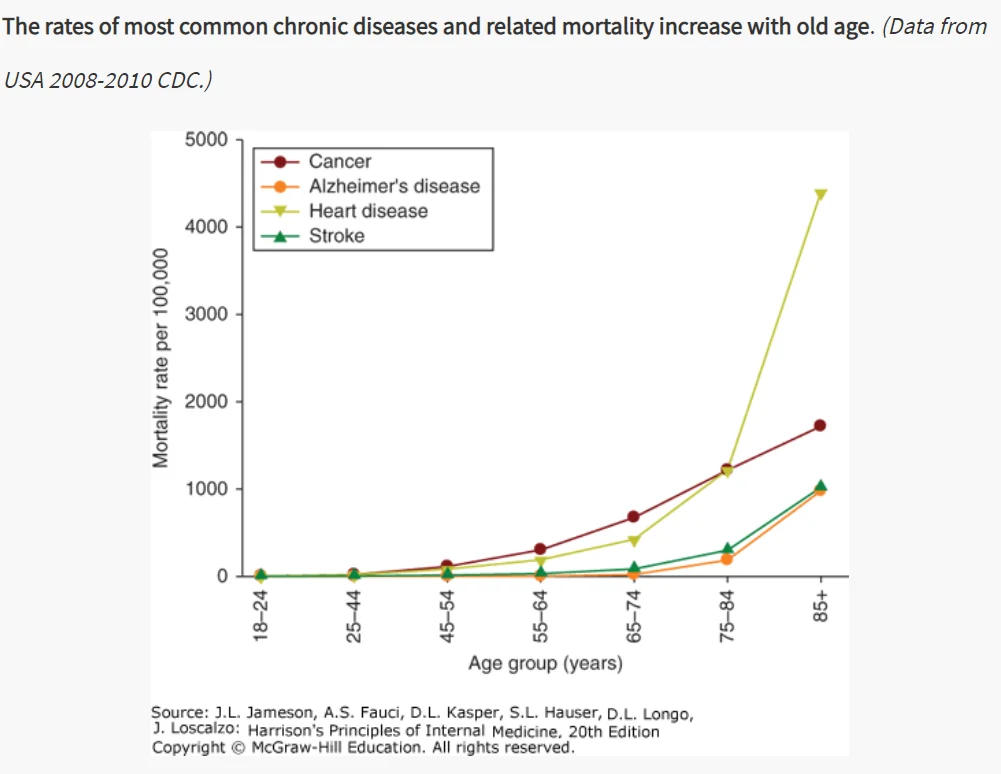

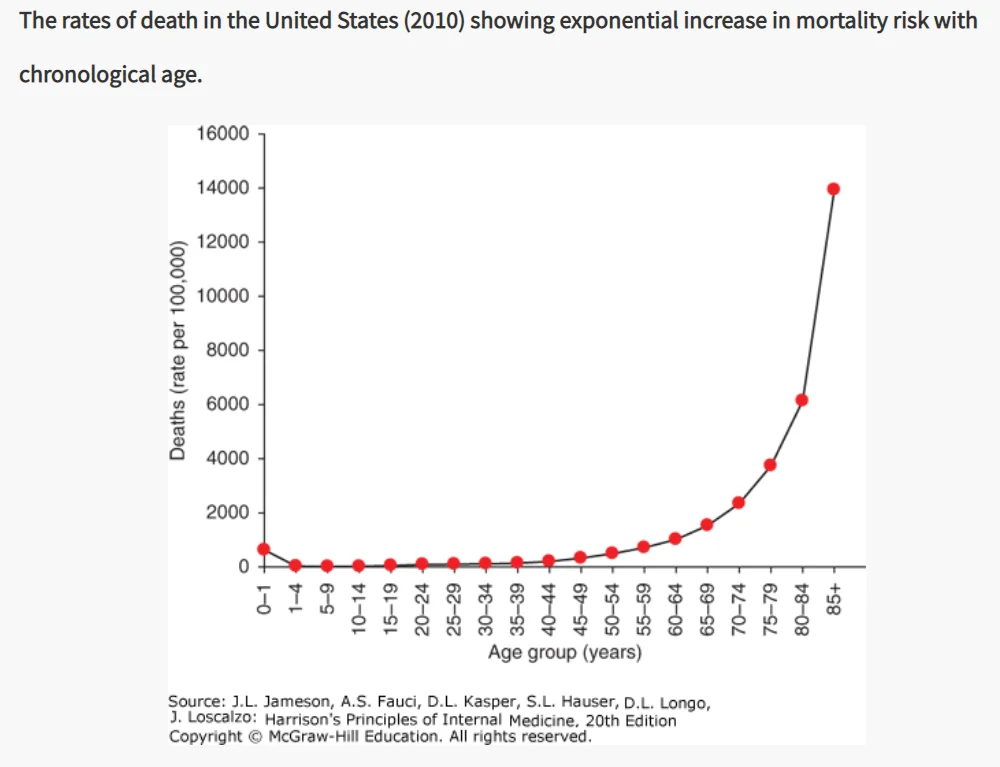

Of course, you could try to put a positive spin on this and look at retirement as a time of financial independence, when, either because you receive a pension or you have enough savings, you can enjoy life without having to go to work every day. This is a much better way to look at it, but we must account for the fact that most people who retire do so either because they hit retirement age or because other circumstances, such as ill health, forced them to retire early [9]—not because they managed to save up enough to retire in their 40s. The health of average retirees doesn’t interfere just with their ability to work but also to enjoy life in general. Most people over the age of 65 suffer two or more chronic illnesses [2,3,4]; the risk of developing diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, and so on skyrockets with age [5], and your financial independence (not to mention your life in general) would be a lot more enjoyable if you didn’t have to put up with any of these.

Retirement 101

The takeaway here is that retirement exists out of necessity more than desire, and even if you try to look at it from a different angle, you’ve still got the problem of the burden represented by age-related diseases. Given these facts, it’s important to understand how retirement works before we can establish if and why the feared pension crisis expected in a few decades from now is actually going to happen and whether life extension will make the problem better or worse.

A pension is a regular payment typically paid monthly to retirees. It can be paid to individuals by governments or employers, or it can come from personal savings, often in the form of special individual retirement accounts that provide some tax incentive to save. This three-pillar system, devised around a hundred years ago, exists in several countries around the world. The purpose is to provide an income after people stop working, i.e. during retirement until death.

Often, pensions can be received only after a certain age or number of years of work and would be deferred if you retire before the minimum is reached; if you decide to retire at age 30, well before you hit retirement age or have worked anywhere near the minimum number of years that you were supposed to, you’re going to wait for a while before you see a dime from your pension.

The funding of a pension depends on the type of pension. In the case of government pensions, like those paid by Social Security in the U.S., the funding is a combination of individual contributions (paycheck deductions) and government funding. Federal and state regulations are in place to ultimately ensure that the future pension income “belongs” to each individual contributor, but of course, contributions that you pay out today aren’t simply set aside for thirty years until you can collect them; they’re used to pay the pensions of present-day retirees; similarly, the money owed to pay your pension will come from the contributions of the workforce at the time of your retirement.

Why a crisis might be on its way

This pension system works well under the assumptions made back when it was devised, but, a hundred years later, things aren’t quite the same anymore.

For example, in the 1930—when the US Social Security system was conceived—the average life expectancy at birth was about 58 for men and 62 for women, whereas the retirement age was 65. This doesn’t mean that everyone checked out before they could cash in, because life expectancy at birth was pulled down by a higher infant mortality; in reality, people who reached adulthood had respectable chances to make it to retirement age and go on to collect their pensions for up to about 13 years; that is, just about before they hit age 80. However, in the year 2015, life expectancy at birth in the US was 79.2, which is around the maximum age that people were expected to reach at the dawn of the pension system; in 2014, the remaining life expectancy at age 79 of people in the US was 8.77 years for men and 10.24 for women. Therefore, in a worst-case scenario, people today can expect to live at least well above the maximum expected lifespan of the 1930s, and, in a best-case scenario, ten additional years. (From the point of view of the pension payer, best- and worst-case scenarios are probably the other way around.) The global average life expectancy in 2015 was 71.4, and even though the remaining life expectancy at that age varies depending on the country, it’s not difficult to see why the funding costs of pensions are mushrooming—simply put, people are living for longer; therefore, they need to be paid pensions for longer—longer than the pension system was designed to handle.

This spells trouble already, but there’s more bad news. As noted above, the global number of people over age 60 is projected to increase significantly in a few decades’ time, more than doubling between 2017 and 2050 (from 1.0 to 2.1 billion), whereas the 10-24 age cohort is expected to increase by a meager 200 million (from 1.8 to 2.0 billion) and the 25-59 cohort by 0.9 billion (from 3.4 to 4.3 billion) [1]. In particular, the number of people aged 85 and above is projected to grow more than threefold, from 137 million to 425 million, over the same span of time. Speaking of pensions alone, this is like having a piggy bank that a fast-growing number of people keeps drawing from and a slow-growing number of people puts money into. (As a side note, the number of children aged 0-9 is projected to stay the same between 2030 and 2050—that is, in twenty years’ time, we won’t have any more future contributors than we used to, while the people needing those contributions will have grown by 0.7 billion over the same 20 years.)

These two facts—the increase of life expectancy and the decrease of fertility rates—constitute what is known as population aging, which is pretty much the core of the problem; external factors that make matters worse, as some people maintain, are poor decision-making and unrealistic promises by politicians and, in general, the people managing pension systems. These might be the result of a lack of understanding of the problem or simply not genuinely caring about the consequences, but, in any case, making clear decisions on the actions to be taken is not an easy task, as tinkering with policies and rates relies on hard-to-predict information, such as the average lifespan of pensioners of a specific pension plan.

In addition, unrealistic investment expectations add to this growing pension crisis. The higher the assumed rate of future investment returns, the less funding is needed to have a “fully funded” pension plan. Currently, the high assumed rates reduce the apparent problem. For instance, the average rate of return on US state pension plans is assumed to be 7.5% per year; meanwhile, investment experts would say a return expectation of 6.5% is much more realistic, and if this assumption is correct, then even more pensions are in danger of running out, and others, previously thought to be only somewhat underfunded, become drastically underfunded. The result is that there is much talk of pension reforms, but the political unpopularity of touching retirement pensions or reducing the unrealistic promises causes continued procrastination.

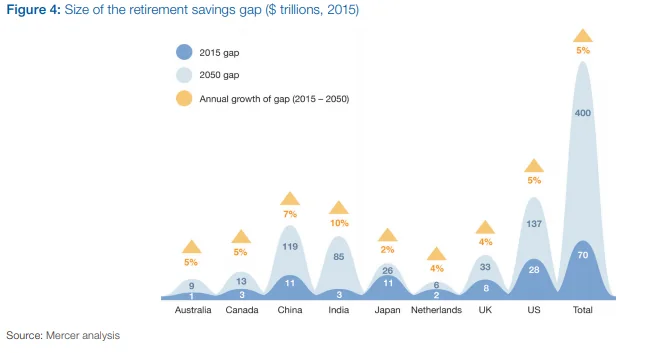

The situation is depressing, in the U.S. and in several other countries. While U.S. Social Security is running low—with the average retiree having only 65.7% of their Social Security benefits remaining after out-of-pocket spending on medical premiums, for example—and expected to run out of money in 2034, Citigroup estimates that twenty OECD countries have unfunded or underfunded government pension liabilities for a mind-boggling total of $78 trillion; China, for example, is expected to run out of pension money shortly after the US, in 2035. In a September 2018 report, the National Institute on Retirement Security warned that the median retirement account balance among working-age Americans is zero and that nearly 60% of working-age Americans do not own any retirement account assets or pension plans. In the press release of the same report, the report’s author, Diane Oakley, stated that retirement is in peril for most working-class Americans, and according to an analysis by Mercer, in a World Economic Forum report, there’s plenty of reasons to believe her, as the US pension funding gap is currently growing at a breakneck rate of $3 trillion a year, reaching $137 trillion in 2050.

World Economic Forum. “We’ll Live to 100 – How Can We Afford It?” May 2017

The icing on the cake: geriatrics

Pensions constitute quite a bit of money paid to people for around two decades until they die, and whether or not we can afford this, it would still be better if we weren’t forced to spend so much money in this way; even worse, we effectively throw even more money out the window by paying for geriatrics, something that most retirees are worried about.

Money spent on healthcare is generally money well spent, but only if it actually improves your health. The problem with traditional geriatrics is that it acts on the symptoms of age-related diseases rather than their causes. The diseases of aging are the result of a on complex interaction between different, concurrent processes of damage accumulation taking place throughout life; this means that, as a rule of thumb, the older you are, the more damage that you carry around. This means that any treatment aimed at mitigating age-related pathologies that does not act on the damage itself or its accumulation is destined to become progressively less effective, like shoveling water with a pitchfork out a lake while a river continually dumps more in.

Generally, geriatric treatments don’t directly affect the damage or its accumulation, so they cannot eliminate age-related diseases and become less and less useful as you age. Some kinds of geriatric treatments are actually geroprotectors—that is, they are able to interfere with the damage or the accumulation of damage and may help prevent diseases—but are often administered too late in the game, when pathologies have already manifested. Geriatrics is decisively not the best bang for the buck, even though it is presently better than nothing at all.

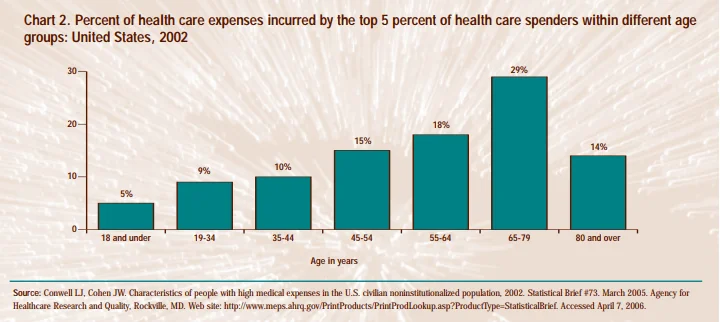

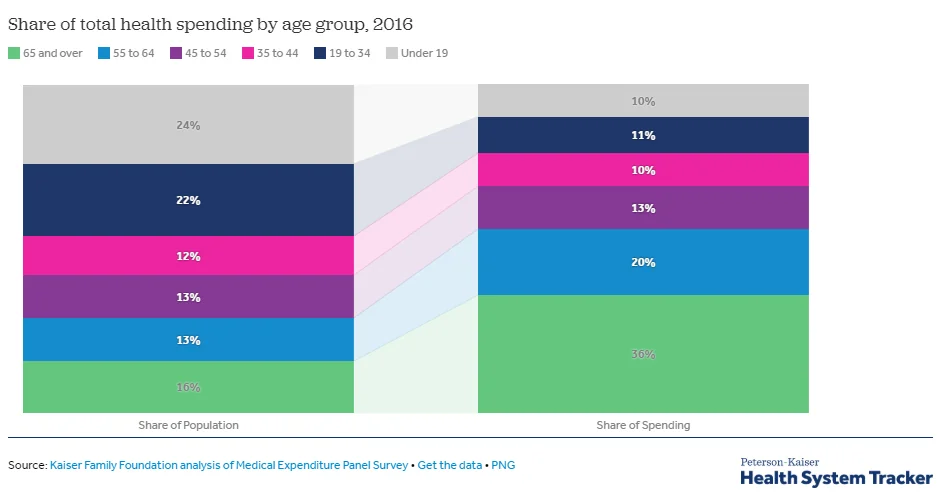

It doesn’t come cheap, either; according to a MEPS report, in 2003, the elderly constituted less than 25% of the Medicaid population but 26% of Medicaid spending; the report finds, unsurprisingly, that chronic conditions contribute to higher healthcare costs, and among the top five most costly conditions are diabetes and heart disease, two diseases typical of old age. Even less surprisingly, in 2002, people over 65 constituted 13% of the US population but accounted for 36% of total US personal health care expenses.

A 2004 study in Michigan found that per capita lifetime health expenditures were $316,000 for women and $268,700 for men (part of the discrepancy is to be attributed to women’s longer lifespans), of which one-third is incurred during middle age and more than another third is incurred after age 85 [6] for people fortunate enough to live that long. Again according to MEPS, in 2016, the average health spending in the US for people over the age of 65 was $11,316; for comparison, the sum total of all the other age cohorts from 0 to 64 was $13,587, only about $2,200 more. The cumulative spending for the 65+ cohort—that is, the average total of yearly expenditures for a US citizen at least 65 years old—was nearly $170,000. Again in 2016, people aged 65 and over accounted for 16% of the US population while constituting 36% of the total health spending.

A report by Milken in 2014 found that, in 2003, about $1.3 trillion was thrown out the window in the US because of the treatment costs and lost productivity related to chronic diseases; the same report projects that, in 2023, the loss will amount to $4.2 trillion.

A 2018 study focusing on out-of-pocket spending for retirees found that the average household that turned 70 in 1992 will incur $122,000 in medical spending over the rest of their lives, and that the top 5% and 1% will incur $300,000 and $600,000, respectively [7]. This paper also found that Medicaid significantly helps the poorest households with their expenses, and it must be noted that, past a certain age, remaining lifetime healthcare costs stop growing and tend to stabilize (for no other reason that the people in question don’t have much life left during which they could spend money on healthcare), but whether the money spent on geriatrics, nursing homes, and so on is a lot or a little, or is spent by you personally or by the government, somebody is going to spend it on something that will not give your health and independence back and is not going to make your life much better. If we must spend it, we might as well do so on something that will actually restore your health.

To top it all, when you consider that American workers aren’t saving that much, a single major medical event past retirement could wipe however little they had set aside.

The costs of caring for older people don’t stop here; they affect their family caregivers as well. As highlighted by the National Center on Caregiving, taking care of a disabled family member may impact the caregiver financially, emotionally, and even health-wise; caregivers are more likely to suffer from stress and depression, are prone to illness themselves, and lose, on average, nearly $700,000 over their course of their lives. When you take into account population aging, it’s clear that this trend can only worsen and put more strain on society.

Life extension: friend or foe?

Now that we have a clearer idea about the potential pension crisis looming ahead and the costs of pensions and geriatrics, it’s time to discuss whether life extension would make the problem better or worse.

It all depends on how you understand life extension. The term per se is somewhat misleading, in that many people often imagine a longer, drawn-out old age in which ill health and the consequent medical expenses and pensions are extended accordingly, just as in the nightmares of social security planners. This is most definitely not what life extension is about, and it’s obvious that extending old age as it is right now would not be a solution to the problem of pensions (or even desirable for whatever other reason). Simply prolonging the duration of life without also prolonging the time spent in good health (if at all possible to a significant extent) wouldn’t solve any problem, and as a matter of fact, it would worsen existing ones; people would be sick for longer, thereby increasing the already exorbitant amount of suffering caused by aging, and they would need pensions and palliative care for longer, probably pushing our social security systems well over the edge. (As a side note, this is what geriatrics does: it delays the inevitable, prolonging the time spent in ill health by making you a wee bit less sick for a longer time.)

However, lifespan and healthspan—that is, the length of your life and the portion of life you spend in good health—aren’t causally disconnected; you don’t just drop dead because you’re 80 or 90 irrespective of how healthy you are. The reason we tend to die at around those ages is that our bodies accumulate different kinds of damage in a stochastic fashion; as time goes by, the odds of developing diseases or conditions that eventually become fatal go higher and higher, even though which specific condition will kill you depends a lot on your genetics, lifestyle, and personal history. The idea behind life extension isn’t to just “stretch” lifespan; rather, the idea is to extend healthspan, that is preserving young-adult-like good health well into your 80s or 90s, and the logical consequence of being perfectly healthy for longer is that you will also live for longer. Significant life extension only follows from significant healthspan extension, and it’s very unlikely that it could ever be otherwise.

Again, the fundamental reason that pensions exist is to economically support people who are no longer able to do it themselves. We need to have such a system in place if we don’t want to abandon older people to their fate. If life extension treatments take ill health and age-related disabilities out of the equation entirely, pensions as we know them today will no longer be needed, because you will be able to support yourself through your own work regardless of your age.

Some people might shudder at the thought of working at age 90, but we can’t help but wonder if they actually realize that the alternative is literally to get sicker and sicker and eventually die; if they prefer that to continuing to work, they probably have more of a problem with the specific line of work they’re in than life extension itself, and they should ask themselves whether they’d trade their health and life in their 40s if it meant that they could quit working earlier. There is, though a better angle to look at this from, and it’s what we mentioned before: retirement as financial independence. Being perfectly healthy for the whole of your life, however long it may be, does not mean you must work each and every moment of it. A longer life spent in good health may more easily allow you to attain sufficient financial independence to retire at least for a while. Unless you’re a billionaire, it’s unlikely that you’ll ever be able to retire for centuries in the current economic system; still, you might be able to enjoy a few years off, and then, say at age 100, celebrate your first century of life in perfect, youthful health by starting off an entirely new career with the same energy and vigor you had when you started the first one in your 20s.

Even if you don’t manage to save enough to retire by yourself, we should not forget that a pension system where people retire for a few years and then go back to work, producing wealth once more rather than just consuming it for decades, is the Holy Grail of social security; governments would have a much easier time paying for your pension for, say, five years, knowing that in five years, you’ll be making your own living again. Your insurance, or whoever pays for your medical expenses, would also be extremely happy to know that you have no chronic conditions to be taken care of—and most importantly, so would you. In a situation like this, a pension crisis is unlikely to happen because pensions would not be a necessity anymore. Even if it happened that pension funds ran dry for whatever reason and push came to shove, people would be able to support themselves through their own work—they’d have to postpone their retirement for some time, but that would be okay, because whatever their age they’d still be fully able-bodied.

This is the best-case scenario: a world where aging is under full medical control, just like most infectious diseases today. There’s also a possibility that this won’t come to pass as soon as we’d like and that we’ll achieve only partial control over aging, for example by successfully extending your healthspan by a few years. Even in this more modest scenario, the financial benefits would be enormous, with an estimated value of over $7 trillion over the course of fifty years [8], which is a benefit worth pursuing whether a pension crisis will happen or not.

Of course, it’s a good idea to sit down and attempt to do the math on a case-by-case basis to see for a fact which countries would effectively have significant economic incentives to endorse, and perhaps even financially support, rejuvenation therapies for their own citizens, but a 2018 report of the International Longevity Centre in the UK provides reasons to be rather optimistic. Titled Towards A Longevity Dividend, the report discusses the effects that life expectancy has on the productivity of developed nations, based on nearly 50 years of demographic and macroeconomic OECD data of 35 different countries; the results of this analysis can be summarized easily: life expectancy is positively correlated with a country’s productivity across a range of different measures. Indeed, the analysis found out that life expectancy seems to be even more important for a country’s productivity than the ratio of young (working) versus old (retired) people. The conclusions of the report’s author are that a longevity dividend, i.e. global economical benefits derived by an extension of healthy lifespans, may be there for society to reap.

We should also not forget that life experience is an asset; while work experience may easily become obsolete time and time again over the course of a very long lifespan, the wisdom and knowledge that older workers may have accumulated may make them excellent mentors and drivers of further progress and innovation.

Summing up

If life extension were simply the prolongation of the period of decrepitude at the end of life, it would make little sense to pursue it. It would do nothing to improve our health, and to add insult to injury, it would exacerbate an already uncertain global financial situation. However, life extension is not this; it’s a significant extension of our healthspan, from which an extension of lifespan logically follows, and as such, it has the potential not just to rid us of age-related diseases altogether but also to solve the financial problems caused by the necessity of pensions and geriatrics by mitigating or eliminating our need for them.

People working in social security can probably sleep more soundly if the undying elderly of their nightmares are replaced with rejuvenated, productive, and independent elderly whose health no longer depends on how long ago they were born.

Literature

[1] United Nations (2017). World Population Prospects: the 2017 Revision. See also World Population Ageing 2017 Highlights, pp. 1 and 6.

[2] Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook.

[3] Harris JR, Wallace RB. The Institute of Medicine’s New Report on Living Well With Chronic Illness. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:120126.

[4] Bell, S. P., & Saraf, A. A. (2016). Epidemiology of multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 32(2), 215-226.

[5] Niccoli, T., & Partridge, L. (2012). Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Current Biology, 22(17), R741-R752.

[6] Alemayehu, B., & Warner, K. E. (2004). The Lifetime Distribution of Health Care Costs. Health Services Research, 39(3), 627–642.

[7] Jones, J. B., De Nardi, M., French, E., McGee, R., & Kirschner, J. (2018). The Lifetime Medical Spending of Retirees.

[8] Goldman, D. P., Cutler, D., Rowe, J. W., Michaud, P. C., Sullivan, J., Peneva, D., & Olshansky, S. J. (2013). Substantial health and economic returns from delayed aging may warrant a new focus for medical research. Health affairs, 32(10), 1698-1705.

[9] Munnell, A. H., Rutledge, M. S., & Sanzenbacher, G. T. (2019). Retiring Earlier than Planned: What Matters Most? (No. ib2019-3).