The Longevity World Meets in Dublin for a Second Time

- Science and political concerns were both discussed at this conference.

Last year’s inaugural Longevity Summit Dublin conference was a good start. Its second iteration, held in August this year, was universally acclaimed for being even bigger and better. Just like the last time, this conference was marked by a considerable presence of longevity advocates alongside scientists and entrepreneurs.

Unfortunately, Lifespan.io executive director Stephanie Dainow, who was slated to talk at the Summit, had to cancel due to personal reasons. Lifespan.io’s troubles didn’t end there: upon my arrival in Dublin, I went down with COVID and was only able to make it to the conference’s last day. This is why this roundup appears more than a month after the actual event: I had to wait for the videos of the talks to become available to be able to bring you the highlights.

On a brighter note, the dates for next year’s conference have just been announced. Let’s meet in Dublin Royal Convention Centre on June 13-16, 2024.

As usual, we are only able to bring you a handful of the talks, and we apologize to all the great speakers who didn’t make the cut.

An update on RMR

The conference’s soul and one of its organizers, Dr. Aubrey de Grey, head of Longevity Escape Velocity Foundation, delivered a much-anticipated update on LEVF’s large-scale experiment into Robust Mouse Rejuvenation (RMR). Lifespan.io was among the first to report on this endeavor in an interview with de Grey. RMR’s goal is to at least double the remaining lifespan of 19-month-old mice, which, without interventions, is about a year.

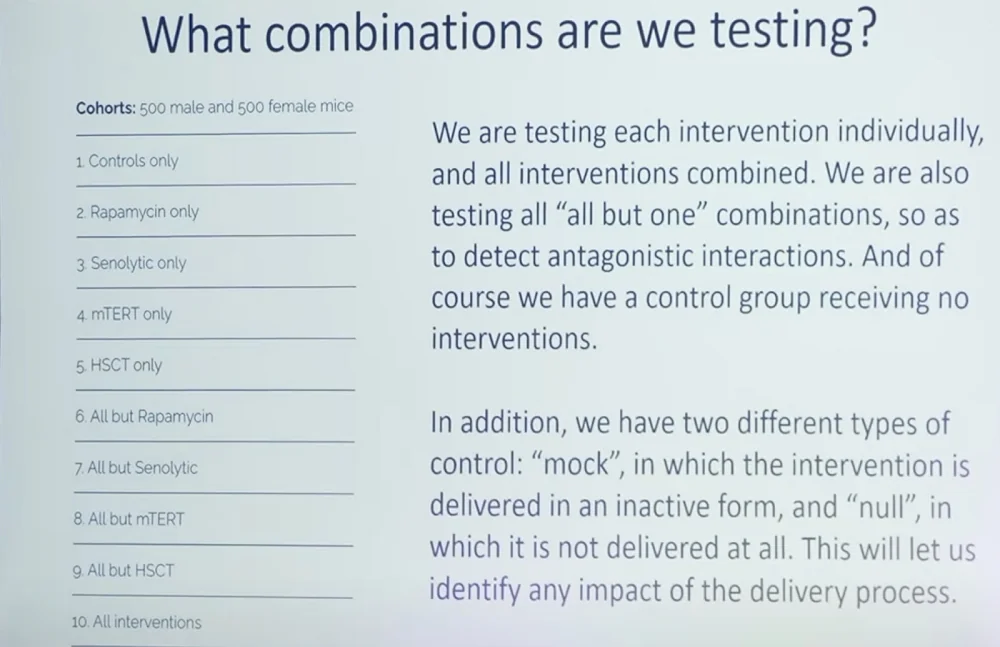

The experiment’s first stage, commenced in February, uses various combinations of four interventions: rapamycin, telomerase gene therapy, young hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and the senolytic navitoclax.

De Grey explained the rationale behind the various aspects of the experiment’s design. First, all interventions significantly differ from each other. Second, data exists that links them to lifespan extension in mice. However, the strength of the evidence is not uniform (for navitoclax, it’s the weakest, but including a senolytic in the mix seemed the right thing to do).

RMR-1 uses 1000 mice divided into 10 groups, including one control group. According to de Grey, the “all but one” groups allow the researchers to identify antagonistic interactions between the therapies. These researchers are measuring “a diverse range of aspects of physiological and cognitive health.” De Grey stressed the need for collaboration in analyzing the tissues of sacrificed mice and called for fellow scientists to reach out.

De Grey talked about several additional interesting details, such as the effectiveness of telomerase therapy in mice being counterintuitive, given that mice, unlike humans, express their own telomerase throughout life in most tissues. De Grey’s explanation is that in mice, the mechanisms for preserving telomeres are still relatively ineffective, which is why supplementing telomerase seems to work.

The researchers are already planning the second stage (RMR-2), although financial issues remain. The new stage will be just as expensive: the total cost depends on the choice of interventions, but it will be at least $3.5 million. Among the current frontrunners are partial cellular reprogramming, exercise, and hyaluronic acid synthase from naked mole rats, which might be the key to those animals’ legendary longevity.

De Grey mentioned the elephant in the room: the fact that successes in mice have a poor rate of translation into humans. “My intuition”, he said, “is that rejuvenation therapies are more likely to translate”. De Grey stressed that geroscience needs to show “dramatic results” in order to convince the general public to support the longevity cause.

Communicating the longevity message

Andrew Steele, a physicist turned longevity advocate, presented a perfectly orchestrated TED-style talk, showcasing how longevity advocacy in front of a live audience should be done.

In recent years, Steele has become a major figure in the field due to his book “Ageless”, which got a raving review from Lifespan.io, and his formidable social media presence.

Steele began with the bold assertion that the biggest obstacle in developing anti-aging therapies isn’t scientific but social: “a chronic lack of awareness.” Steele maintains that aging biology “needs a PR makeover as much as it needs scientific advancements”, since drastically increasing funding should also boost scientific output.

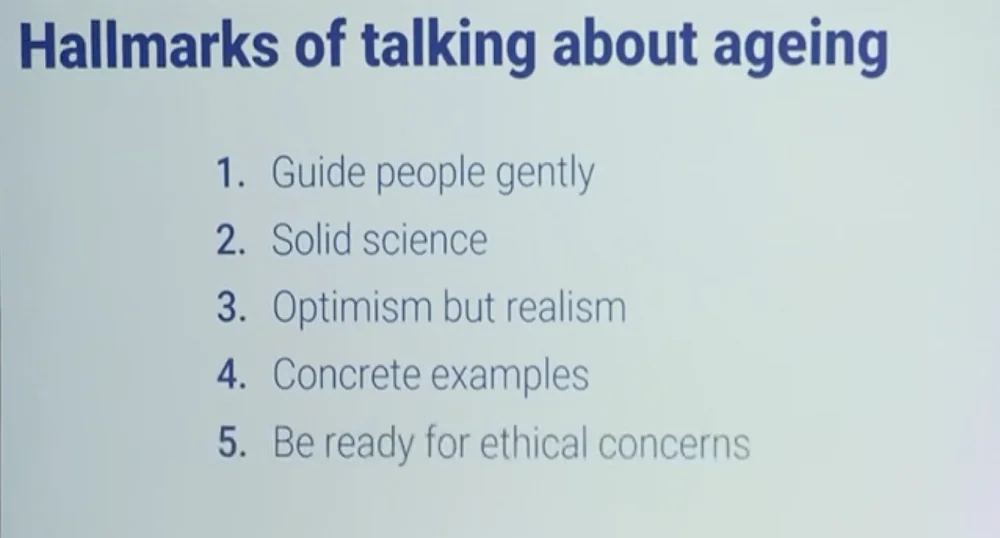

Steele then walked the audience through the main dos and don’ts of communicating anti-aging research to the general public. Aging, he said, is an easy conversation to start, because everyone ages and is intrigued by the idea of living longer and healthier, but it’s difficult to navigate well.

According to Steele, most people do not realize just how much more likely they are to die with age, so the first “exhibit” Steele usually presents to its audience is the Gompertz curve, which shows human mortality doubling every eight years. People also tend to underestimate their risk of getting a debilitating disease and spending their last years in agony as opposed to quietly dying in their sleep, so reminding them of the prevalence of age-related diseases might jolt them out of their complacency.

Unprepared people should be guided into the conversation about life extension gently, such as by presenting them with solid scientific advances instead of “the latest and shakiest developments.” The Hallmarks of Aging, despite being contested in their current form by many people in the field, provide a good example of concrete aging-related biological processes that can be modified to extend lifespan. “You don’t have to make wild promises in order to give people an optimistic take-home message”, Steele said.

As a physicist, Steele often points out that curing aging doesn’t go against the laws of physics. Long-lived species, of which Steele is particularly fond of the Galapagos tortoise, provide a living example of negligeable senescence.

Longevity popularizers should be ready for ethical concerns, overpopulation being the most popular one. Steele pointed out that researchers working on cancer or dementia don’t get asked questions of this kind: “Nobody would stick their hand up after my talks and say, ‘Andrew, are you not worried that all these childhood leukemia survivors are going to get bored with all those extra years of life that you’ve impeded them with?’”

Steele proposes pointing out that geroscience is just another preventative field of medical research like vaccination. Another nifty trick is to reverse the premise by asking the interlocutor to imagine an overpopulated world without aging. Would they introduce aging to solve the overpopulation problem or to kill a particularly brutal dictator? The answer would probably be a hard “no”. As Steele points out succinctly in his book, “aging is not a moral solution to any problem.”

Bryan Johnson on Blueprint and the danger of partying

Just several months ago, few people in the longevity community had heard about Bryan Johnson. Today, he is arguably the most discussed individual in our field. Neither a scientist nor a medical professional, Johnson gained his fame by pushing himself to the limit in search of maximum rejuvenation. Lifespan.io dedicated a feature article to Johnson and his Blueprint regimen, which consists mostly of a healthy diet, exercise, good sleep, selected drugs and supplements, several more exotic treatments, and lots of testing. Johnson prides himself on being the “world champion in rejuvenation”, which he measures with epigenetic clocks and various other markers. Overall, his efforts cost him around two million dollars a year.

Recently, Johnson began appearing at longevity conferences, although he rarely does so in person because he avoids flying farther than two time zones in order to preserve his precious sleep quality. In Dublin, Johnson appeared via Zoom to be interviewed by Aubrey de Grey.

The first question de Grey asked was, how did Johnson get interested in aging and ended up applying this knowledge to himself? Apparently, after spending two years in Ecuador in his early twenties and witnessing extreme poverty, Johnson realized that “the only thing he wanted to do was to improve the human race.” Years later, after creating and selling his company Braintree Venmo, he started looking for that one thing “that would have a measurable impact” and came to a conclusion that this worthy cause was to extend human lifespan and ultimately bring an end to death.

Johnson does tend to think big; some people would say too big. His philosophy postulates that humans need to reinvent themselves in preparation for the AI-driven future. As a first step, they should realize that health-wise, algorithms can take better care of them than they can of themselves. Johnson measures himself extensively and makes health-related decisions based exclusively on those measurements, albeit with the help of a 30-strong team of healthcare professionals.

Johnson is clearly imbued with a sense of mission that he deems important for humanity as a whole. Quality of sleep, he says, is paramount for achieving “soberness of thought”, because he is “searching for the invisible and can’t do that on less-than-ideal sleep.”

De Grey pointed out that “there’s been a lot of partying” going on at the conference, and many people haven’t had enough sleep, consciously sacrificing a fraction of their health for pleasure. “You must be a pretty monomaniacal person”, he said to Johnson. “Do you view yourself as such?”

In response, Johnson lamented people’s “acceptance of death”. While at the moment, death might seem inevitable, “we are baby steps away from superintelligence, and when it arrives, we don’t have the capacity to know what will happen, it’s a complete wall”, he said referring to the concept known to many as the singularity. According to Johnson, while in the past, it would have been reasonable to say, “live a little, party, have fun”, this “ideology of death” is clearly inadequate today. “With Blueprint”, he said, “I’m trying to introduce the conversation about life and death.”

“The most tragic outcome”, according to Johnson, “would be to not be included in the future”, and people should be barely concerned with anything else. “The only thing on our to-do list as a species is to not die”, he said, which might raise the eyebrows of people who see other urgent problems around them. However, answering a tongue-in-cheek question from de Grey, Johnson conceded that after we achieve the LEV, “partying will become rational again”.

The question, which I unfortunately was not chosen by the moderator to ask, is whether putting all your eggs in one basket by prioritizing lifespan over everything else is wise risk management, considering that our chances of being around when radical life extension is achieved are unclear?

George Church on the promise of gene and cell therapies

This famed geneticist gave a talk titled “A focused plan for extreme longevity (not mere age reversal or slowing)”. The title itself represents a bold departure from the current mainstream view that extreme longevity is improbable.

Church, however, admitted that even studying longevity is hard, in particular because human longevity’s standard deviation is about 15 years, which means prohibitively long clinical trials. A more practical approach would be to cure multiple diseases of aging.

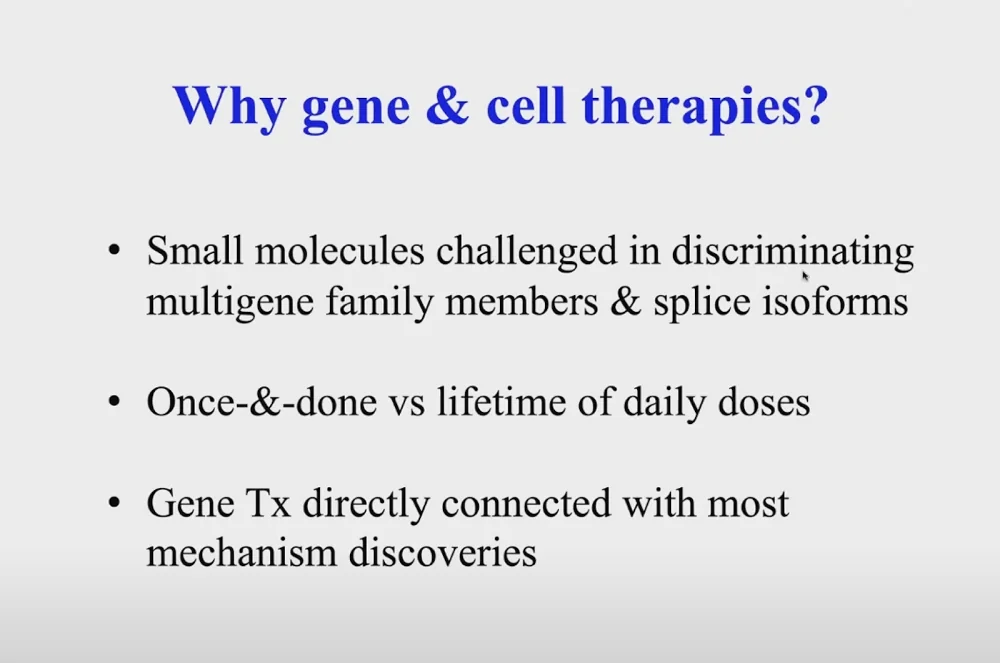

To do so, Church said, we need personalized precision medicine based on gene and cell therapies. If we want to reach meaningful life extension (for instance, by exploiting amazing mechanisms developed by long-lived species), “small molecules or nutrition won’t take us there, we have to focus on the genome and its effects.”

This can be done in two ways: somatic gene therapy and germline engineering. The former’s advantages include shorter clinical trials and fewer ethical concerns. On top of that, germline therapies can hardly help the currently living. Germline therapies, however, have their own pluses, such as delivery to all tissues and “a million-fold lower off-target” (clonally introducing a single cell rather than doing therapeutics on billions of cells at once).

In one slide, Church summarized the main advantages of gene and cell therapies:

Illustrating the last point, Church mentioned that his lab was able “to take 45 observations from literature and turn them into 54 gene therapies in a couple of months”.

Just like with reading and writing genome, the price of gene therapies has gone down exponentially, culminating in vaccines that cost as low as 2$ per dose (many people tend to think that gene therapies are expensive, because they are mostly associated with rare diseases where the price can indeed exceed three million dollars).

Church then continued to describe the recent advances in the field of gene therapy, such as “exceptional machine learning tools to improve delivery.” Scientists are getting more adept in “borrowing” mechanisms from other species – such as those that protect from radiation. A radiation-sensitive organism, Church reported, can be made radiation-resistant with as few as four genes. In a different example, 69 germline edits helped create pigs that can be used to grow and transplant human organs without immune rejection.

Work is being done on making cells and organisms resistant to all viruses. This year, this dream was achieved in one case in a microorganism in which serine was swapped with leucine. Those two amino acids are very different chemically, and if you swap them in a way that does not hurt the host cell, viral genes get mistranslated. This was tested on numerous viral strains, and the research is moving into mammalian species.

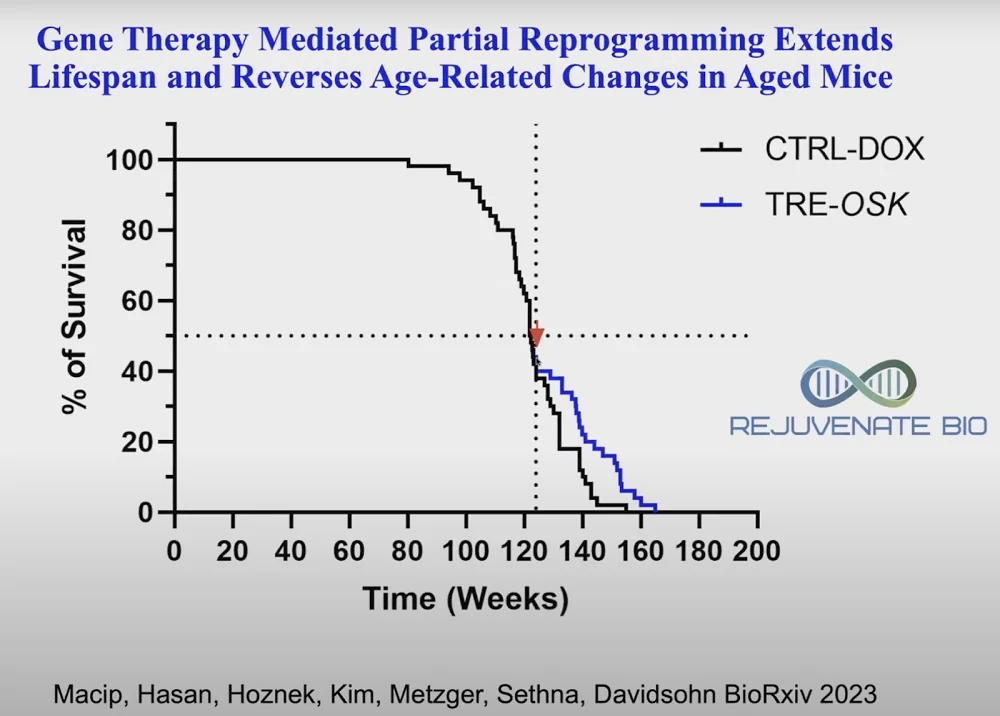

Recent research has highlighted four combination gene therapies that can target multiple age-related diseases at once. A company that Church co-founded, Rejuvenate Bio, which is working on a gene therapy for cardiac problems, is now starting human clinical trials. A mouse trial of three of the Yamanaka factors (OSK) given very late in life, when most of the mice have already died, led to a substantial increase in remaining lifespan. The results were published on BioRxiv this year:

Disrupting telomeres for cancer treatment

Vlad Vitoc of MAIA Biotechnology presented the remarkable advances that his company has achieved with its unconventional anti-cancer treatment based on telomere disruption.

In humans, the activity of telomerase, the telomere-building enzyme, stops in most somatic cells in early childhood. Age-related telomere shortening contributes to the appearance of mutations, including oncogenic ones. In cancer cells, however, telomerase is reactivated, essentially giving them an infinite replicative potential. MAIA’s compound, THIO, short for 6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine, is picked by telomerase and placed in the telomere structure, disrupting it. The telomere collapses, and the cancer cell dies in 24-72 hours. THIO is a small molecule that penetrates the blood-brain barrier, which makes it suitable for treating brain cancers.

The treatment directly kills 70-90% of cancer cells. Moreover, resulting telomere fragments trigger a strong immune response, and if THIO is followed by immunotherapy (checkpoint inhibition), this, according to Vitoc, results in near complete response with no recurrence thanks to anti-tumor immune memory. Curative effects when used in sequential combination with immunotherapy were observed in many tumor types.

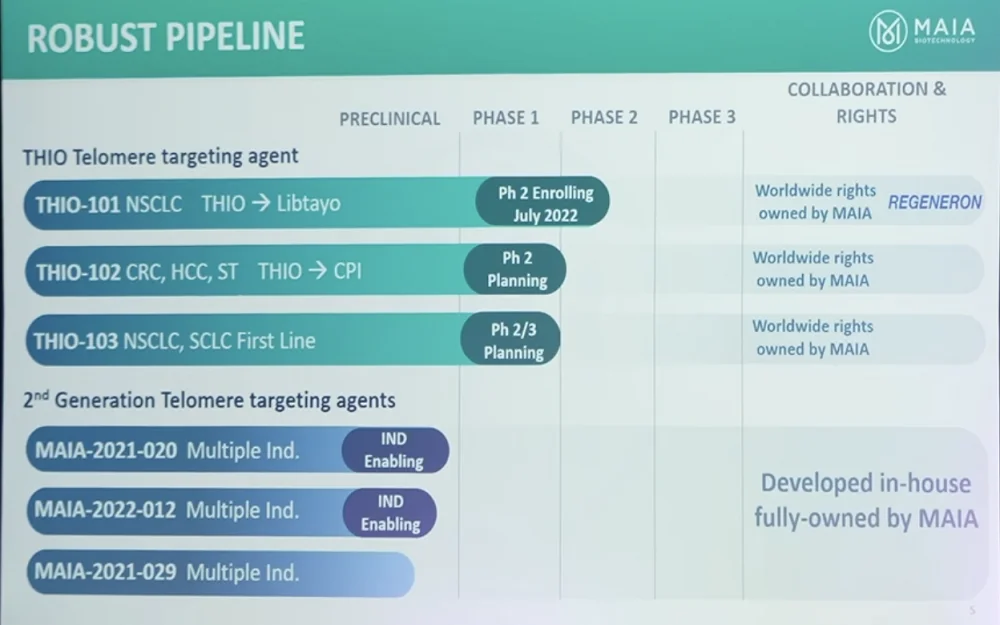

THIO is in the clinic now, and other telomere-targeting agents are in the pipeline too. MAIA has partnered with Regeneron, a manufacturer of an immune checkpoint inhibitor, for a Phase II Go-to-Market Accelerated Approval trial for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which is currently underway. The second Go-to-Market Accelerated Approval trial, THIO 102, starts later this year in several tumor types. For the second generation of agents, the IND enabling process is underway, and they will go into clinical trials next year.

So far, Vitoc said, THIO is demonstrating an excellent safety profile, far superior to that of the standard of care. Preliminary survival data shows that the first two patients, who have advanced stage 4 metastatic NSCLC and were heavily pre-treated using the current standard of care, continue to be alive after about a year since receiving the treatment, with no new interventions after the study treatment. Other patients seem to be on the same track.

In preclinical mouse trials, the company has seen even better results for colorectal cancer, with 100% complete response and no recurrence, even when re-challenged with twice the amount of cancer cells. Similar results have been obtained for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Building a longevity network state

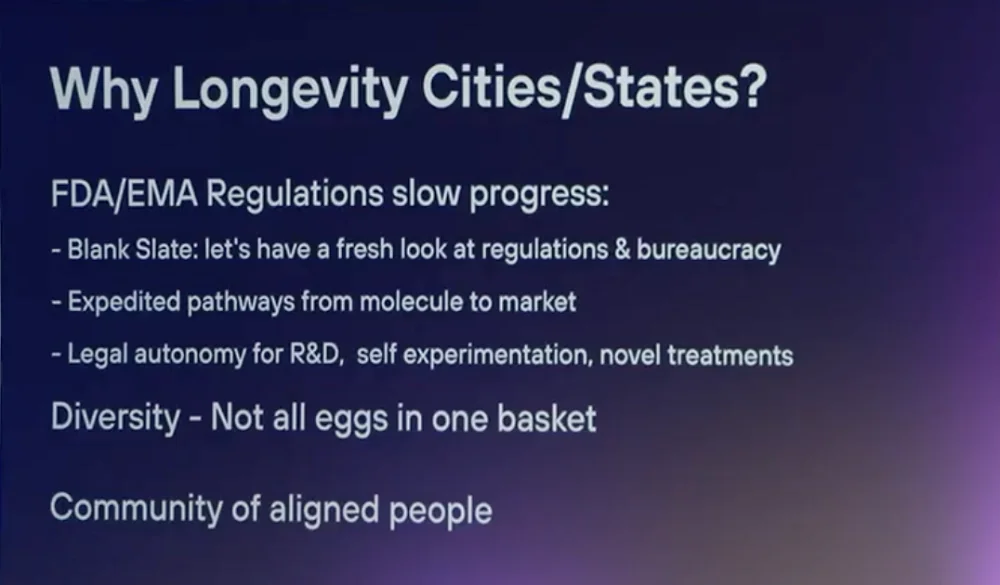

Max Unfried of the National University of Singapore and VitaDAO talked about a novel topic in the longevity field: the possibility of creating longevity network states. This was also discussed at length in Zuzalu, a pop-up city that existed for two months earlier this year in Montenegro (read our full coverage of that event, including a section on network states).

Unfried began by reminding the audience that through millennia, human societies underwent innumerable changes: “We moved from chiefdoms to city states, then to kingdoms, then to nation states, and the question is what comes after that? Can we use the Internet to start new countries, new jurisdictions?”

A network state is a new proposed form of long-term collaboration between people aligned along the same values and goals. According to its most prominent ideologist Balaji Srinivasan, a network state is “a highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states”. Gradually, citizens of a nascent network state begin acquiring real estate and building a decentralized economy that can be leveraged to elevate the state’s status and eventually lead to recognition.

A longevity network state is united by the goal of extending human lifespan and healthspan. As such, it can unite scientists, entrepreneurs and enthusiasts, providing perks such as a favorable regulatory microclimate that would allow to get drugs to market faster, giving biology-savvy people an expanded right to try new treatments, and creating a longevity-friendly ecosystem. How can a longevity network state build up its GDP? According to Unfried, the possible avenues include medical tourism and cheaper clinical trials due to lighter regulations.

Building a network state does not require too many people. The smallest countries have populations in the tens of thousands. Iceland’s population is less than 400 thousand. A network state could have 50-200 thousand citizens and a GDP of 5-10 billion dollars.

Network states might sound like a crazy idea today, Unfried admitted, but the idea that aging is modifiable also sounded crazy not that long ago. Today, the world is moving forward much faster than even several years ago. Dozens of startups, societies, and institutes are working on various aspects of the network state paradigm. Unfried reminded the audience that people can be extremely quick and efficient in building new cities.

According to Unfried, VitaDAO, has already hit the first few milestones on the road to a longevity state, creating a community with a mission, which is capable of collective action and backed by a cryptoeconomy. Now, VitaDAO is in the process of crowdfunding physical nodes. However, gaining diplomatic recognition is still far out (“Let’s talk in ten years”, Unfried said).

At the end of his talk, he announced Zuzalu 2.0, which is organized mainly by Laurence Ion from VitaDAO and Niklas Anzinger. Named Vitalia, it will be based on Roatan Island and span over eight weeks in early 2024.

Can neurons be replaced?

Jeanne Loring, Professor Emeritus at Scripps Research institute, gave a talk on treating Parkinson’s diseases by neuron replacement. What made Loring’s appearance particularly interesting is that her company, Aspen Neuroscience, is a less-known longevity-related investment by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, who famously poured 180 million dollars into Retro Biosciences.

A hallmark of Parkinson’s is the gradual death of dopamine neurons. By the time symptoms appear, more than half of dopamine neurons in the region of the brain called substantia nigra are already dead. Current drug therapies increase dopamine production, improving the effectiveness of remaining neurons, but they cannot prevent degeneration.

All this makes Parkinson’s a good candidate for cell replacement therapy. For the last several years, attempts have been made to replenish the dying neurons with new neurons and glia derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

Most of those current experimental therapies are allogeneic, that is, they use cells from one source to treat multiple patients. Since those are not originally the patient’s own cells, the treatment requires at least a year of immunosuppression. Aspen, on the other hand, uses autologous cells taken from a skin biopsy. Fibroblasts are grown in a dish, reprogrammed with Yamanaka factors and turned into neurons using a “robust and very reliable differentiation method”, according to Loring.

Making cells from every individual patient is harder than just growing a cell line in a bioreactor. On the other hand, it is easy to redose with autologous cells, since there are no rejections. If cells divide for a long time (such as with allogeneic cell lines), they tend to acquire genomic aberrations in culture. Moreover, a selection process begins, with mutations in the tumor suppressor gene p53 being one of the most selected for. This is less of a problem if you grow up just a few cells, but rigorous quality control helps too.

Loring reported on exciting proof-of-concept studies in rats, where dopamine neurons were depleted in one brain hemisphere and replenished using iPSCs. In a paper published in July, Loring’s group showed that there is a small window between the cells being too immature and able to differentiate into cell types other than neurons and too mature and not being able to form new synapses. The trick is to stop the differentiation process at the right time. At the end of her talk, Loring delivered “the big news”: Aspen has been approved for a Phase I/IIb trial.

Learning from long-lived species

Steven Austad of University of Alabama at Birmingham who have researched long-lived species for decades, presented a talk intriguingly titled “The most overlooked but informative models of successful aging”.

Austad started with an overview of exceptional longevity in the animal kingdom. “Nature is smarter than you are”, he said, “because it had billions of years and combinations to try to overcome the inherently destructive processes of aging.”

One of geroscience’s biggest problems is that, humans being exceptionally long-lived, it is not easy to improve on an already impressive result. Mice, the most popular model organism, on the other hand, are “very inept at aging”, which makes it easy to cause mice to live longer.

However, there are species that are better at battling the degenerative processes of aging than humans are, at least in some aspects. Austad calls these species “Methuselah’s Zoo”, which is also the name of his recently published book. Some of them can plainly outlive humans, while others live exceptionally long lifespans for animals of their body weight, and we can learn a lot from all of them.

Yet, there is one group of long-lived animals that has been mostly overlooked: birds. All the birds you see around, Austad said, including the most unassuming ones like pigeons and sparrows, are much longer-lived than most animals of their size. The longest-lived wild bird that we know of is an albatross named Wisdom, and it’s at least 72 years old.

It’s not just how long birds live, but how long they stay healthy: right to the end of their lifespan. Wisdom is still reproducing and parenting, which is grueling work for an albatross. Birds have a constellation of traits that should predispose them to a short lifespan, like a high metabolic rate, which is unsurprising given the physical demands of flight. Birds also have high body temperatures and high glucose levels to support those demands. They should have been diabetic, but for the protective mechanisms they developed. Despite all this, they age much slower than mammals.

Birds are small, they are easy to keep in aviaries, and people have a lot of experience in bird husbandry. All this makes birds potentially great model animals for studying aging.

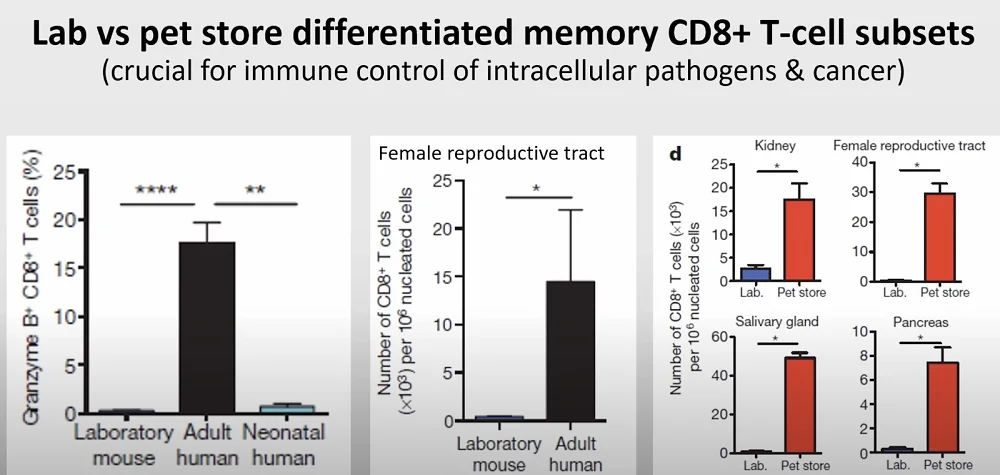

The second “overlooked but informative species” Austad mentioned was… mice. Where’s the catch? He was talking not about lab mice but about mice living in the wild or in pet stores. Austad lamented the fact that while geroscience has made it to the point where we’re ready to move things into the clinic, high failure rates in trials put this potential in jeopardy.

Here are some of the reasons for those failure rates, according to Austad. First, since mice are “feeble at resisting aging”, they don’t teach us much about aging in humans. Second, species have idiosyncrasies which are enhanced by inbreeding, domestication, and the standard lab environment, which Austad called “bizarre”: it never changes, it’s cold, microbiologically depauperate to increase replicability, and unstimulating sensorily, which can also be relevant, as research shows.

There are two types of trials, Austad said: explanatory trials evaluate an intervention under ideal (narrow) circumstances, while pragmatic trials do so under “real world” conditions. Most pre-clinical trials are of the first kind to make things consistent (the Intervention Testing Program, ITP, is a good example), while clinical trials must be more realistic. At this point, many promising treatments fail.

Austad mentioned a few peculiar cases to drive his point home. In one of them, a drug for leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis, after passing the pre-clinical trials in mice with flying colors, failed miserably in clinical trials, causing life-threating side effects such as cytokine storms. Several years later, the same effects were observed in wild-derived mice, showing just how inadequate a lab mouse’s immune system is in mimicking that of a human.

This is highly relevant to clinical trials since immune function affects multiple aspects of aging, including cancer resistance and senescent cell accumulation.

Austad finished by reiterating that translational research requires pragmatic trials with multiple genotypes/species,and more realistic (preferably multiple) environments.

Updates from Capitol Hill

In his talk, Dylan Livingston, founder of the Alliance for Longevity Initiatives (A4LI), the first US organization solely devoted to longevity-related lobbying, recounted its accomplishments during the first 20 months of its existence.

In February of this year, A4LI was instrumental in the formation of the Longevity Science Caucus in the House of Representatives, a first-of-its-kind bipartisan initiative led by the Congressmen Gus Bilirakis, a Republican from Florida, and Paul Tonko, a Democrat from New York. Four of the five members are also on the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee, which has jurisdiction over biomedical research in the US.

A4LI is also active on the state level. Working withstate senator Kenneth Bogner, the Alliance successfully lobbied for an expansion of Montana’s Right-to-Try Act. This act initially gave terminally ill patients access to all experimental drugs, which is more or less in line with federal law. They updated Montana’s law to go much further, ensuring that healthy people also have access to those therapy after they have passed Phase I clinical trials to establish their safety.

This law, according to Livingston, can establish Montana as a medical tourism hub and provide tangible benefits for the longevity industry, such as by allowing companies to start receiving revenues earlier and getting real-world data for their drugs.

A4LI’s next initiative is setting up a congressional briefing on longevity science in January 2024. It is anticipated to be a major two-day event, featuring a fundraising dinner with DC political leaders and insiders along with members of the longevity industry. Day two will be dedicated to the briefing itself and meetings with the members of the Caucus. The idea is to spread the longevity message and educate as many members as possible. “This will be the spark that will ignite governmental action in the US”, Livingston said.

Next, Livingston talked about ARPA-H, “the brainchild of the current administration” that had been set up to be a cancer moonshot initiative, but since then expanded in scope. Now, APRA-H is looking for any transformative technological breakthroughs in healthcare, and Livingston invited the audience to apply for funding.

According to Livingston, geroscience is on the verge of becoming mainstream in the corridors of power. The Senate Appropriations Committee recently came out with its bill for 2024, and it contained multiple mentions of geroscience, which would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. In its section related to ARPA-H, the bill calls for the creation of two programs: for biomarkers of aging and for epigenetic reprogramming. “This could be huge for the field”, Livingston said.