High-Protein Diets Have Few Benefits in Mice

- Mice that ate less protein were healthier overall.

A new study suggests that high protein intake leads to fat gain and worse metabolic outcomes, but some of these effects are blocked by resistance training. Low protein consumption resulted in less muscle gain but did not affect strength [1].

The protein debate

One of the most hotly debated topics in nutritional science is how much protein a person should consume. On the one hand, protein restriction promotes health and longevity in animal models [2]. Some human longitudinal studies show an association between low protein consumption and lower rates of diabetes and some other age-related diseases. Clinical trials in metabolically unhealthy people have found that low protein consumption increases leanness and insulin sensitivity [3].

On the other hand, there is some evidence that at least older people should increase their protein intake to counter age-related muscle loss [4]. Some scientists argue that current dietary guidelines put the recommended protein intake way too high, and others believe that it should be even higher. In short, the jury is still very much out.

Protein, muscle, and fat

Any new piece of information is a welcome addition to our body of knowledge on protein consumption. In this new study, the researchers paired different levels of protein consumption in mice with resistance training in order to investigate the interplay between them.

Male mice were fed either a low-protein (LP, 7% of calories from protein) or a high-protein (HP, 36%) diet. Each group was divided into two subgroups. One pulled an increasing load of weight down a track three times per week for three months, and the other pulled an unloaded cart (sham treatment).

The two diets contained the same number of calories. Caloric intake from fat was kept at 19%, but carbohydrates were reduced in the HP diet. Five weeks into the experiment, the mice started pulling the carts, which is a recently validated model of resistance training in rodents that does not lead to a reduction in body weight.

Generally, mice on the LP diet ate more than mice on the HP diet, which is consistent with the notion that protein provides a satiating effect. Since the two diets had the same caloric density, HP-fed mice ended up consuming fewer calories than LP-fed mice. Despite that, the former gained more weight. At the end of the 18-week experiment, unexercised HP-fed mice were much heavier on average than unexercised LP-fed mice, gaining both more lean mass and fat mass. Interestingly, lean mass gain in HP-fed mice was not affected by exercise. However, in line with previous studies, weight pulling completely blocked fat mass gain in those mice.

Better glycemic control and no strength disadvantage

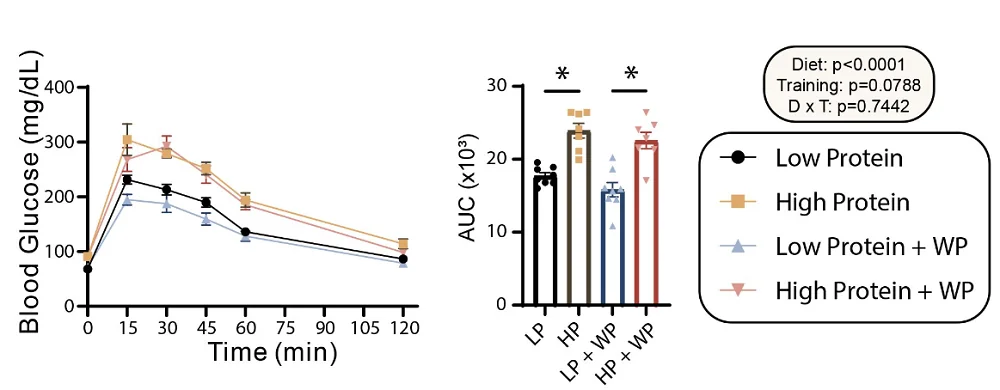

Previous research has shown that both low-protein diets and resistance training improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. These researchers concur, as they found that LP-fed mice showed better glucose tolerance compared to HP-fed mice. Weight pulling also seemed to have some effect on glucose tolerance, but it didn’t reach statistical significance. Similar effects were observed on fasting insulin levels and insulin sensitivity. Quite surprisingly, while diet did not affect triglyceride levels, weight pulling seemed to increase them. Neither diet nor exercise affected blood levels of cholesterol.

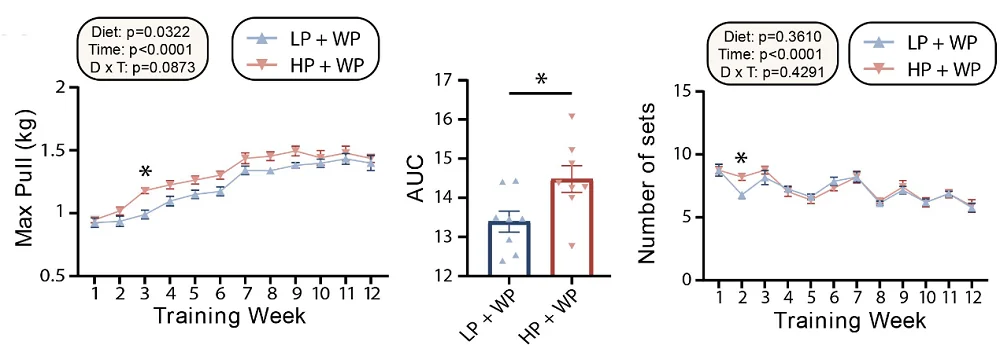

Despite being more muscular, HP-fed mice did not show a massive advantage in strength over their LP-fed counterparts. While initially, the maximum weight they could pull was higher than in the LP-fed group, the difference almost never reached statistical significance, and by the tenth week, LP-fed mice seemed to have caught up. Throughout the experiment, there was no difference between the two groups in the maximum number of sets. Any advantage that HP-fed mice seemed to have in weight pulling, disappeared in two other fitness tests, inverted cling and rotarod, where LP-fed mice actually performed marginally better.

High protein intake may be only for looks

In total, a high-protein diet led to both fat and muscle gain and to worse metabolic outcomes. Resistance training protected the mice from fat gain but not from a decrease in glycemic control, and it was associated with higher triglyceride levels. A low-protein diet did not seem to affect physical performance in exercised mice, despite not causing an increase in muscle mass.

The researchers suggest that high protein consumption might be especially ill-advised for sedentary people, as it might lead to fat gain and metabolic problems. In other words, people who eat a lot of protein may benefit from regular gym visits to shed off some of the effects, and people who are after metabolic health and strength, rather than a ripped exterior, might want to consider low-protein diets.

As usual, these results, however interesting, should be taken with caution due to the study’s limitations, as it was conducted on exclusively male mice of the same age and breed. The researchers themselves call for more rigorous studies that would include female and aged mice, and, in the future, humans.

Literature

[1] Trautman, M. E., Braucher, L. N., Elliehausen, C., Zhu, W. G., Zelenovskiy, E., Green, M., … & Lamming, D. W. (2023) Resistance exercise protects mice from protein-induced fat accretion. eLife.

[2] Mirzaei, H., Raynes, R., & Longo, V. D. (2016). The Conserved Role for Protein Restriction During Aging and Disease. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care, 19(1), 74.

[3] Ferraz-Bannitz, R., Beraldo, R. A., Peluso, A. A., Dall, M., Babaei, P., Foglietti, R. C., … & Foss-Freitas, M. C. (2022). Dietary protein restriction improves metabolic dysfunction in patients with metabolic syndrome in a randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients, 14(13), 2670.

[4] Mendonça, N., Hengeveld, L. M., Visser, M., Presse, N., Canhão, H., Simonsick, E. M., … & Jagger, C. (2021). Low protein intake, physical activity, and physical function in European and North American community-dwelling older adults: a pooled analysis of four longitudinal aging cohorts. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 114(1), 29-41.