Exercise Variety Is Associated With Lower Mortality Risk

- Variety may be roughly as important as amount.

- Unsurprisingly, people who exercised more had better outcomes than people who exercised less.

- The number of different activities also had significant effects on outcomes.

- As these were groups of health professionals, the least active group may not have been fully inactive.

A new study links exercise variety, defined as regularly engaging in several types of physical activity, to significantly lower all-cause mortality. Exercise amount matters as well, but the effect plateaus quickly [1].

How exactly is it good for you?

“Exercise is good for you” is a stale truism, but researchers continue to uncover new information about how the amount and specific types of physical activity affect our health. A new study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, published in the journal BMJ Medicine, focuses on the relationship between mortality and the variety of physical activity in two large cohorts of health professionals.

The researchers analyzed data from over 100,000 participants across two major long-term studies (the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study) over a period of 30 years. The former study included only women, while the latter only men. Both cohorts were free at baseline of diabetes, cancer, and any cardiovascular, respiratory, or neurological disease. The levels of physical activity were self-reported every two years. In total, almost 2.5 million person-years were recorded.

Metabolic equivalent of task (MET) is the amount of energy expended during an activity compared to energy expenditure at rest, and in this study, activity doses were expressed as MET-hours/week. For example, brisk walking has a MET value of 3.5 to 4.5, meaning it is about four times more energy-demanding than chilling on a couch.

Lower mortality rates for most types of exercise

Habitual engagement in most measured activities was associated with significantly lower mortality rates. For example, compared to people with the lowest activity levels, the people in the highest categories saw risk reductions of 17% for walking, 15% for tennis and other racquet sports, 14% for rowing/calisthenics, 13% for running and weight/resistance training, and 11% for jogging.

Two activities showed surprisingly low effect sizes: bicycling (4% risk reduction) and swimming (1% risk increase, but statistically insignificant). However, this might simply reflect measurement problems, which is a well-known issue for both cycling and swimming [2].

These mortality benefits from single activities appear more modest than in some earlier studies [3]. One possible reason is that in this study, the comparison group was the lowest quintile of activity, which may not reflect true inactivity, especially since these were groups of of health professionals. The authors also used robust protections against reverse causation (when people lower their activity levels after they become unhealthy), which tends to shrink associations.

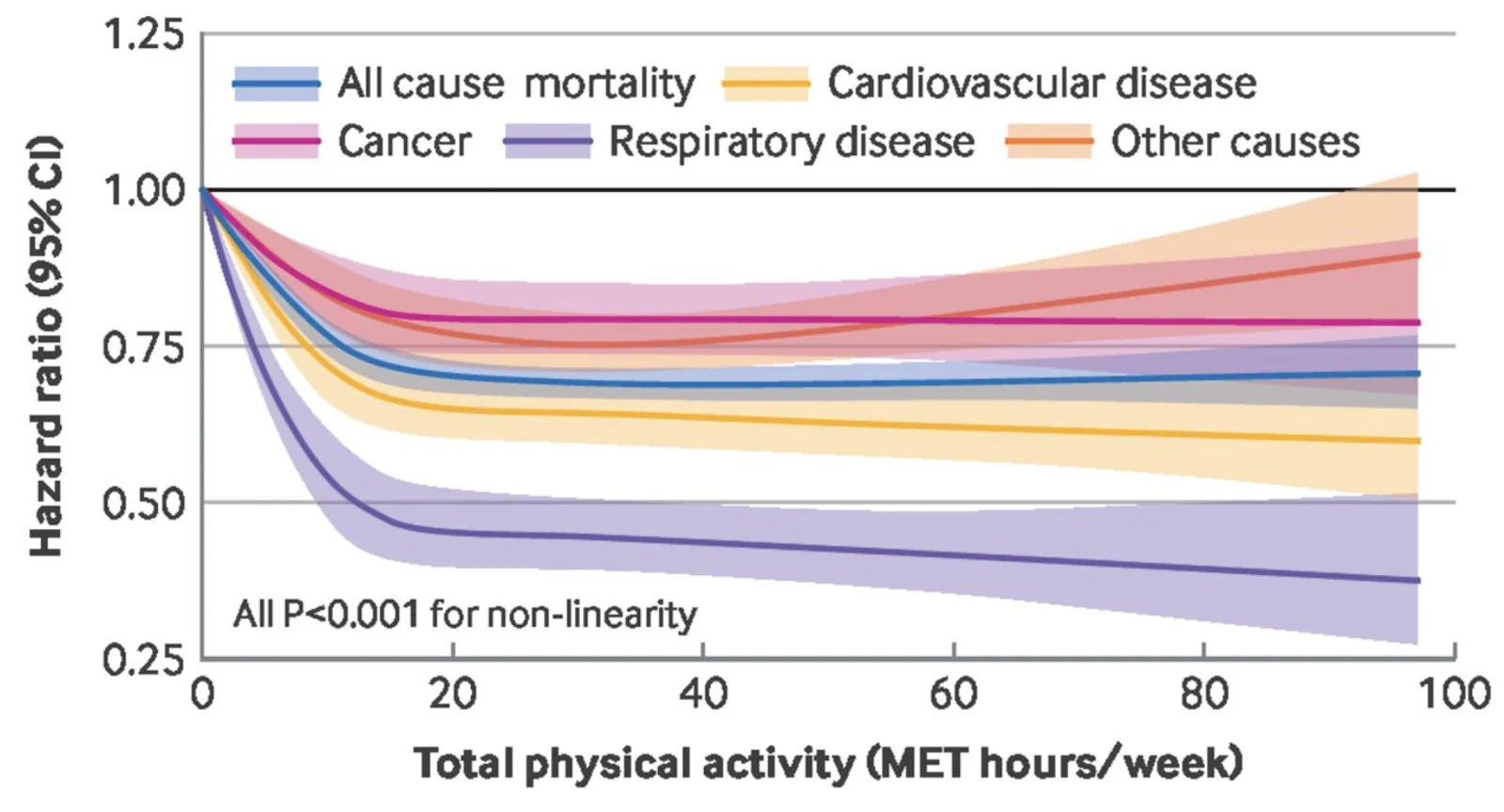

Like many recent studies [4], this one shows that mortality risk plateaus at certain levels of activity rather than decreasing indefinitely. However, here, the benefits of exercise peter out rather quickly (at least for cardiovascular, cancer, and respiratory mortality), around 20 MET-hours per week, which may also be due to the reference group not being completely inactive.

Variety matters (usual caveats apply)

The researchers then compared participants with different levels of variety in physical activity, defined as the number of different types of activity that participants regularly performed. After adjusting for total physical activity, the highest-variety group had about a 19% lower all-cause mortality compared to the lowest, with comparable reductions across major causes.

When they combined people into groups by total activity and variety, the highest on both had about 21% lower mortality compared to the lowest-lowest reference group. The authors report no interaction here, signifying that variety helps across activity levels rather than only at high or low volume.

“People naturally choose different activities over time based on their preferences and health conditions. When deciding how to exercise, keep in mind that there may be extra health benefits to engaging in multiple types of physical activity, rather than relying on a single type alone,” said corresponding author Yang Hu, research scientist at the Department of Nutrition.

Anna Whittaker, Professor of Behavioral Medicine at the University of Stirling, who was not involved in this study, said: “This large-scale longitudinal study adds to what we know about the impact of physical activity on mortality by showing that engagement in a range of different types of physical activity is beneficial for longevity, independently of the total amount of physical activity engaged in. This is likely due to the different types of activity having different physiological effects and helping to meet all of the aspects currently outlined in physical activity guidelines (i.e. moderate intensity exercise, resistance exercise, vigorous intensity exercise, flexibility work, recovery activities).”

Like all populational studies, this one can only show correlation, but not causation, and the results depend on many design choices. While the authors did an admirable job controlling for possible confounders, which included age, race/ethnicity, family history of myocardial infarction and cancer, body mass index, smoking, alcohol intake, energy intake, diet quality, social integration, baseline hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, and (for women) postmenopausal hormone use, it is impossible to rule out residual confounding such as sleep, stress, or the built environment. For instance, it is possible that people who can find the time and energy for various types of activity have more free time, enjoy better sleep, and live in an environment better suited for exercise.

Literature

[1] Han, H., Hu, J., Lee, D. H., Zhang, Y., Giovannucci, E., Stampfer, M. J., Hu, F. B., Hu, Y., & Sun, Q. (2026). Physical activity types, variety, and mortality: Results from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ Medicine, 5(1), e001513.

[2] Harrison, F., Atkin, A. J., van Sluijs, E. M., & Jones, A. P. (2017). Seasonality in swimming and cycling: Exploring a limitation of accelerometer based studies. Preventive medicine reports, 7, 16-19.

[3] Arem, H., Moore, S. C., Patel, A., Hartge, P., De Gonzalez, A. B., Visvanathan, K., … & Matthews, C. E. (2015). Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA internal medicine, 175(6), 959-967.

[4] Garcia, L., Pearce, M., Abbas, A., Mok, A., Strain, T., Ali, S., … & Brage, S. (2023). Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes: a dose–response meta-analysis of large prospective studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(15), 979-989.