Sleep Deprivation Affects Cognition via Myelin Loss

- A lack of sleep impairs the brain's cholesterol processing.

- People who get less sleep have problems with their white matter.

- This was recapitulated in rats, which performed worse on neural and cognitive ability tests when deprived of sleep.

- Administering a drug to restore cholesterol distribution to myelin restored the sleep-deprived rats’ abilities and brought some biomarkers back to normal levels.

A new study links sleep loss to the thinning of the myelin layer, which slows signal transmission in axons. Restoring cholesterol homeostasis reverses the damage [1].

Sleep loss hurts myelin

Sleep quality is a strong extrinsic determinant of longevity [2]. Not only does sleep loss affect cognitive function [3], it has also been linked to a plethora of health problems, including increased dementia risk, cardiovascular disease, and immune dysfunction [4]. However, the underlying mechanisms are still being investigated. In a new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers from Italy and Spain has shed new light on this question.

The team started with scouring through the Human Connectome Project database for correlations between sleep loss and structural problems in the brain. They found a significant negative correlation between sleep quality and MRI-measured white matter microstructural integrity. In other words, poor sleep was linked to worse white matter, and this effect was brain-wide.

Oligodendrocytes are the cells that build myelin sheaths around axons; this myelin layer insulates axons, ensuring swift and faithful signal transmission. The researchers subjected rats to 10 days of sleep restriction and found widespread reductions in white matter integrity, reduced myelin basic protein (MBP) staining in the corpus callosum, thinner myelin sheaths, and fewer oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), all of which point to myelin deficiency.

Importantly, the team then ran a separate chronic mild stress cohort to rule out stress as the driver. Cortico-cortical evoked responses and corticosterone levels were unchanged with stress alone, suggesting that the effects are specific to sleep loss.

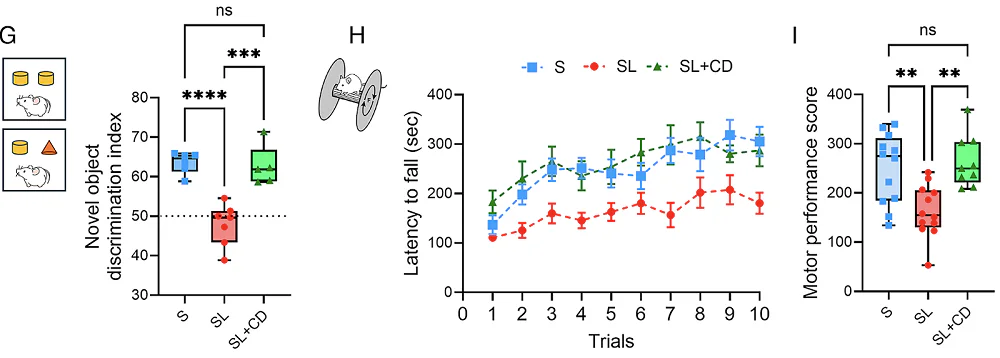

Sleep-restricted rats showed approximately 33% increased latency in transcallosal conduction; essentially, signals traveling between hemispheres were substantially slower. Sleep loss also affected cognitive function, causing worse novel object recognition and motor performance on rotarod, and impaired interhemispheric synchronization of neuronal activity, particularly during NREM sleep.

It’s all about cholesterol

Using transcriptomic data from oligodendrocyte-specific datasets, the researchers found that sleep loss massively dysregulated cholesterol-related pathways: biosynthesis and transport genes were downregulated, while endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and lipid degradation genes were upregulated. “In summary, the analysis of gene expression in oligodendrocytes revealed that sleep loss significantly impaired ER and lipid homeostasis, particularly affecting cholesterol metabolism,” the paper says.

Direct measurements confirmed markedly reduced cholesterol in purified myelin fractions from sleep-deprived mice. This cholesterol loss increased membrane fluidity in the inner leaflet of the myelin membrane, which would weaken the insulating properties of myelin. “Optimal membrane fluidity and curvature in myelin necessitate high cholesterol levels,” the authors explain. “This ensures membrane stability, minimizes ion leakage, and reinforces the insulating properties of myelin membranes.”

The researchers link the observed reduction in myelin cholesterol to deficits in intracellular trafficking and transport mechanisms. Sleep loss caused minimal changes in other lipids. “The impact of sleep loss on major cholesterol-related transcripts was more pronounced in oligodendrocytes than in other brain cell types,” the paper clarifies.

An almost complete rescue

The team reasoned that by boosting cholesterol redistribution during sleep loss, it would be possible to minimize or prevent myelin dysfunctions and restore optimal conduction velocity in rats. They performed a rescue experiment, administering 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (cyclodextrin), a drug that promotes cholesterol redistribution to myelin membranes, via three subcutaneous injections during the 10-day sleep restriction.

When they measured cholesterol in purified myelin fractions afterward, the sleep-loss-plus-cyclodextrin group was statistically indistinguishable from normally sleeping controls: the drug completely prevented the myelin cholesterol depletion that sleep restriction would otherwise cause. Cyclodextrin partially fixed myelin ultrastructure, although it did not reduce the proportion of unmyelinated axons back to control levels, and it didn’t fully restore OPC density in the corpus callosum. The treated animals showed no significant change from baseline, meaning that the conduction delay was fully prevented.

Importantly, the treatment also achieved behavioral rescue. For novel object recognition, sleep-restricted rats had a significantly reduced discrimination index (couldn’t distinguish new from familiar objects), but cyclodextrin-treated sleep-restricted rats performed comparably to controls. On the rotarod, where untreated sleep-restricted rats showed lower motor performance scores, the cyclodextrin group again performed at control levels. The authors note that since animals were given 24 hours of recovery before behavioral testing, residual physical fatigue is unlikely to explain the motor deficits.

Cyclodextrin, however, is not a precision tool. It facilitates broad cholesterol redistribution. While recent work suggests its effects are predominantly on oligodendrocytes, the authors admit that it also might be helping other cell types. While the rescue demonstrates that restoring cholesterol homeostasis is sufficient to prevent the behavioral deficits, further research is required to prove oligodendrocytes are the only cell population that matters.

Literature

[1] Simayi, R., Ficiarà, E., Faniyan, O., Cerdán Cerdá, A., Aboufares El Alaoui, A., Fiorini, R., … & Bellesi, M. (2026). Sleep loss induces cholesterol-associated myelin dysfunction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 123(4), e2523438123.

[2] Cappuccio, F. P., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P., & Miller, M. A. (2010). Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep, 33(5), 585-592.

[3] Killgore, W. D. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in brain research, 185, 105-129.

[4] Shi, L., Chen, S. J., Ma, M. Y., Bao, Y. P., Han, Y., Wang, Y. M., … & Lu, L. (2018). Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis Sleep medicine reviews, 40, 4-16.