Dysbiosis

Humans have 23,000 genes that control the basic functions of our cells. These genes manage everything from heartbeats to hormone levels. However, there is another collection of genes all over and inside our bodies. These genes number around 3 million strong, but they are not us.

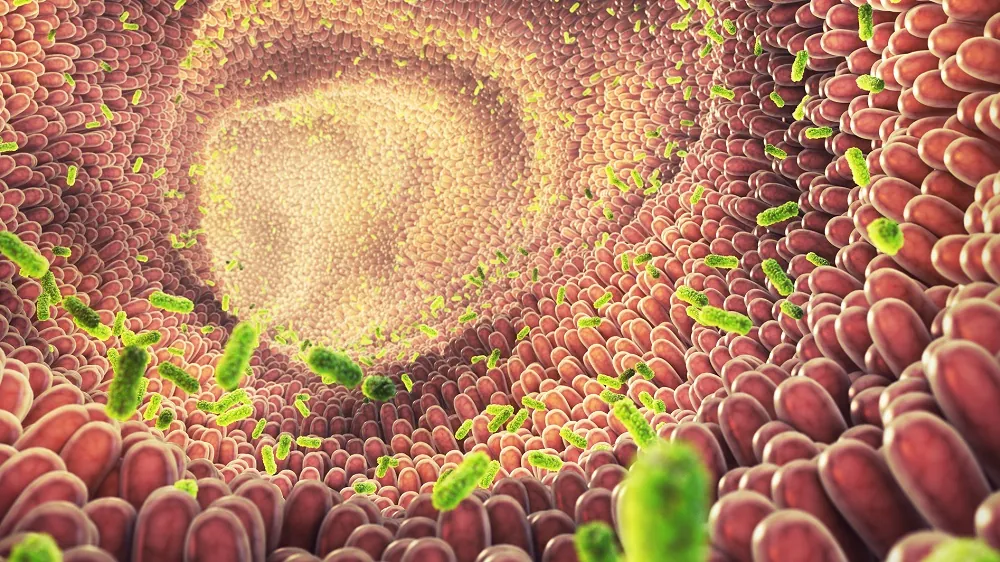

This huge “second genome” is the microbiome. It contains trillions of bacteria, archaea, and viruses. Their combined DNA is much larger than the DNA found in human cells.

When this microbial system is well-tuned, it gives off metabolites, vitamins, and immune signals. These help the host to function smoothly. With aging, however, this balanced symbiosis collapses into dysbiosis, a state marked by lower microbial diversity, leaky gut barriers, chronic inflammation, and metabolic noise.

In youth, the human gut is buzzing with a mix of helpful microbes working in harmony. In aging that harmony declines. The gut instead becomes a chaotic and pro-inflammatory environment.

This decline is so important that López-Otín and colleagues recently upgraded dysbiosis into a full hallmark. It was also placed with chronic inflammation at the “integrative” tier of aging biology.

Studies show that changing the microbiome can speed up frailty. Resetting it can reverse biological aging in mice, humans, and interestingly, in progeroid mouse models.

Aging leads to fewer and different microbial species

Cross-sectional data from more than 9,000 people aged 18 to 101 shows some interesting findings. As we get older, our gut communities become more unique and personalized.

In the healthiest elders, this uniqueness sees a depletion of domineering Bacteroides and a bloom of rarer microbes [1]. Centenarian surveys echo the pattern, spotlighting Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium and bile-acid-tinkering Odoribacter as potential pro-longevity bacterial species [2].

Research on mice has advanced this further. In a group of genetically diverse mouse strains, the patterns of their gut bacteria related to age could predict which mice would live longer. Some mice were expected to live longer, while others were not [3].

Metabolic signatures

Chemical clues in blood and stool tell us how this shifting gut community affects the rest of the body. Indoles are molecules made when bacteria break down the amino acid tryptophan. They appear more often in older adults with strong muscles and low C-reactive protein. C-reactive protein is a marker of inflammation.

In contrast, another bacterial by-product called p-cresol-sulfate keeps turning up in frail seniors [4].

In particular, indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) has stepped into the spotlight. Mouse studies have shown that IPA attaches to the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). It reduces the NF-κB inflammatory switch and strengthens the gut barrier. In some animal models, it may even help lengthen a healthy lifespan [5].

Connecting microbes to aging

The aging microbiome hijacks our bodies systems along multiple converging routes.

Firstly, it increases inflammaging, a smoldering low-grade background of chronic inflammation. When researchers moved gut microbes from old mice to young, germ-free mice, the young mice’s spleens became very active. They showed a rise in hyper-active CD4⁺ T cells and more inflammatory cytokines [6].

Secondly it compromises the gut wall. Harmful bacterial communities gnaw away at tight-junction proteins, letting lipopolysaccharide seep into the bloodstream, fueling metabolic syndrome and cognitive haze.

On the other hand, a 2025 microbiome rejuvenation mouse study showed this can be reversed. Researchers repeatedly dosed old mice with youthful stool and restored those junctions and calmed the inflammation [6-7].

Fecal transfer from young animals to old ones is an interesting idea. This method could potentially lead to a therapy emulating the youthful microbiome.

Thirdly the aging microbiome scrambles the host’s chemical wiring. Bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids decline, leaving colon cells without butyrate. Meanwhile, secondary bile acids can increase cancer risk.

Interestingly, centenarians appear to buck this trend. They store iso-allo-lithocholic acid, a bile acid that has strong antimicrobial effects [8-9].

Gut-educated T cells gradually move from tolerance-promoting regulators toward pro-inflammatory TH17 cells with age. This shift was partly reversed when obese older adults were given Akkermansia muciniphila supplements for twelve weeks [10].

Demonstrating causation though transplants

Proving cause and effect is not easy when dealing with the microbiome. However, there are three lines of research that have provided solid evidence.

First, when healthy stool is transplanted into fast-aging (progeroid) mice, their health and lifespan improve. Delivering just one next-generation probiotic, Akkermansia muciniphila, provides many of those benefits [11].

Second, giving naturally aged mice a young animal’s microbiome helps balance hippocampal metabolites. It also matures microglia and improves maze-running memory. These results were confirmed in a 2025 mouse trial. This trial used “young-trained” donors to improve synaptic plasticity and cognition [12-13].

Essentially young microbiomes can make aged mice biologically younger.

Third, transplanting an aged microbial community into germ-free younger hosts causes a quick rise in cytokines and lipopolysaccharide. This process also reduces germinal-center reactions in Peyer’s patches. As a result, it speeds up inflammaging in otherwise young hosts [14-15].

In a very real sense, old microbiomes make young mice biologically older.

Together, these lines of research make a persuasive causal case. Changing the microbiome’s age alters the host’s biological age along with it. These studies show that dysbiosis meets the López-Otín criteria for being a hallmark of aging. This includes being linked to age, speeding up when worsened, and slowing down with treatment.

Relationships to other hallmarks

The causality of aging is seldom one-directional. Dysbiosis amplifies chronic inflammation, while IL-6-soaked tissues reshape microbial niches.

Mitochondrial dysfunction feeds into dysbiosis, as reactive oxygen species favor facultative anaerobes. Conversely, short-chain fatty acids boosted by a youthful microbiome support mitophagy.

Even epigenetic alterations and telomere attrition intersect with dysbiosis: microbial folate supply modulates DNA methylation, while butyrate is a histone deacetylase whisperer.

Future directions for dysbiosis research

Several open fronts will shape the next decade of “microbiome geroscience.” Large multi-omics datasets now include over 8,000 human stool and blood profiles. These profiles show at least three different “aging-microbiome archetypes.”

Machine learning clocks use gut read-outs to predict age. They can be accurate within 3 years and sometimes do better than DNA methylation tests. This suggests that one stool sample might eventually be better than epigenetic arrays for measuring aging rates [16-17].

Enthusiasm for long-term fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is tempered by potential safety issues, however. Recent studies show that even after careful screening, donor strains can change genes in the recipient’s gut. Now, virome-only transfers (FVT) are being tested as a safer option [18-19].

The gut-brain axis remains a tantalizing therapeutic target. Ongoing trials are changing tryptophan-processing bacteria in Parkinson’s disease. They want to see if manipulating indole and kynurenine production can slow motor decline [20-21].

Precision gene editing has reached the microbiome itself. A 2024 study used phage-packaged base editors to remove a pathogenic gene area from E. coli in situ. This achieved 93% editing without carpet-bombing the gut flora. This strongly suggests that “CRISPR gardening” of resident microbes is feasible [22].

There are also environmental factors at play. Microbiome-friendly dietary practices, using antibiotics sparingly, and simple greenspace exposure that may introduce benign bacteria all vary widely between populations and areas.

Aging doesn’t just apply to human cells; trillions of microbes are involved as well. Dysbiosis is not a passive biomarker but an active switchboard operator, rerouting signals across immunity, metabolism and neuroendocrine lanes.

However, the microbiome is much more malleable than nuclear DNA. It is always changing due to food and environmental factors. Therefore, some future therapies may not look like traditional methods. Instead, they may resemble ecological restoration projects that restore balance to bodily systems.

Literature

[1] Microbiome Ageing in Genetically Diverse Mice. Nat Microbiol 2025, 10, 1032–1033.

[2] Jiang, H.; Chen, C.; Gao, J. Extensive Summary of the Important Roles of Indole Propionic Acid, a Gut Microbial Metabolite in Host Health and Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15.

[3] Litichevskiy, L.; Considine, M.; Gill, J.; Shandar, V.; Cox, T.O.; Descamps, H.C.; Wright, K.M.; Amses, K.R.; Dohnalová, L.; Liou, M.J.; et al. Gut Metagenomes Reveal Interactions between Dietary Restriction, Ageing and the Microbiome in Genetically Diverse Mice. Nat Microbiol 2025, 10, 1240–1257.

[4] Sonowal, R.; Swimm, A.; Sahoo, A.; Luo, L.; Matsunaga, Y.; Wu, Z.; Bhingarde, J.A.; Ejzak, E.A.; Ranawade, A.; Qadota, H.; et al. Indoles from Commensal Bacteria Extend Healthspan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E7506–E7515.

[5] Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qing, M.; Dang, W.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, L.; Qing, D.; Zhang, J.; et al. Trends in Intestinal Aging: From Underlying Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025.

[6] Fransen, F.; van Beek, A.A.; Borghuis, T.; El Aidy, S.; Hugenholtz, F.; van der Gaast – de Jongh, C.; Savelkoul, H.F.J.; de Jonge, M.I.; Boekschoten, M. V.; Smidt, H.; et al. Aged Gut Microbiota Contributes to Systemical Inflammaging after Transfer to Germ-Free Mice. Front Immunol 2017, 8..

[7] Sommer, F.; Bernardes, J.P.; Best, L.; Sommer, N.; Hamm, J.; Messner, B.; López-Agudelo, V.A.; Fazio, A.; Marinos, G.; Kadibalban, A.S.; et al. Life-Long Microbiome Rejuvenation Improves Intestinal Barrier Function and Inflammaging in Mice. Microbiome 2025, 13.

[8] Lu, Y.; Du, J.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Therapeutic Potential of Isoallolithocholic Acid in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Peritoneal Infection. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2025, 78, 166–180.

[9] Sato, Y.; Atarashi, K.; Plichta, D.R.; Arai, Y.; Sasajima, S.; Kearney, S.M.; Suda, W.; Takeshita, K.; Sasaki, T.; Okamoto, S.; et al. Novel Bile Acid Biosynthetic Pathways Are Enriched in the Microbiome of Centenarians. Nature 2021, 599, 458–464.

[10] Kang, C.H.; Jung, E.S.; Jung, S.J.; Han, Y.H.; Chae, S.W.; Jeong, D.Y.; Kim, B.C.; Lee, S.O.; Yoon, S.J. Pasteurized Akkermansia Muciniphila HB05 (HB05P) Improves Muscle Strength and Function: A 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16.

[11] Bárcena, C.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Mayoral, P.; Garabaya, C.; Durand, S.; Rodríguez, F.; Fernández-García, M.T.; Salazar, N.; Nogacka, A.M.; Garatachea, N.; et al. Healthspan and Lifespan Extension by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation into Progeroid Mice. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1234–1242.

[12] Cerna, C.; Vidal-Herrera, N.; Silva-Olivares, F.; Álvarez, D.; González-Arancibia, C.; Hidalgo, M.; Aguirre, P.; González-Urra, J.; Astudillo-Guerrero, C.; Jara, M.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation from Young-Trained Donors Improves Cognitive Function in Old Mice Through Modulation of the Gut-Brain Axis. Aging Dis 2025.

[13] Parker, A.; Romano, S.; Ansorge, R.; Aboelnour, A.; Le Gall, G.; Savva, G.M.; Pontifex, M.G.; Telatin, A.; Baker, D.; Jones, E.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transfer between Young and Aged Mice Reverses Hallmarks of the Aging Gut, Eye, and Brain. Microbiome 2022, 10.

[14] Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Shrestha, A.; Duff, A.F.; Kontic, D.; Brewster, P.C.; Kasperek, M.C.; Lin, C.H.; Wainwright, D.A.; Hernandez-Saavedra, D.; Woods, J.A.; et al. Aging Amplifies a Gut Microbiota Immunogenic Signature Linked to Heightened Inflammation. Aging Cell 2024, 23.

[15] Stebegg, M.; Silva-Cayetano, A.; Innocentin, S.; Jenkins, T.P.; Cantacessi, C.; Gilbert, C.; Linterman, M.A. Heterochronic Faecal Transplantation Boosts Gut Germinal Centres in Aged Mice. Nat Commun 2019, 10.

[16] Shen, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; Hornburg, D.; Wu, S.; Snyder, M.P. Nonlinear Dynamics of Multi-Omics Profiles during Human Aging. Nat Aging 2024.

[17] Gopu, V.; Camacho, F.R.; Toma, R.; Torres, P.J.; Cai, Y.; Krishnan, S.; Rajagopal, S.; Tily, H.; Vuyisich, M.; Banavar, G. An Accurate Aging Clock Developed from Large-Scale Gut Microbiome and Human Gene Expression Data. iScience 2024, 27, 108538.

[18] Behling, A.H.; Wilson, B.C.; Ho, D.; Cutfield, W.S.; Vatanen, T.; O’Sullivan, J.M. Horizontal Gene Transfer after Faecal Microbiota Transplantation in Adolescents with Obesity. Microbiome 2024, 12.

[19] Mao, X.; Larsen, S.B.; Zachariassen, L.S.F.; Brunse, A.; Adamberg, S.; Mejia, J.L.C.; Larsen, F.; Adamberg, K.; Nielsen, D.S.; Hansen, A.K.; et al. Transfer of Modified Gut Viromes Improves Symptoms Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Male Mice. Nat Commun 2024, 15.

[21] Iwaniak, P.; Owe-Larsson, M.; Urbańska, E.M. Microbiota, Tryptophan and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptors as the Target Triad in Parkinson’s Disease—A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25.

[22] Brödel, A.K.; Charpenay, L.H.; Galtier, M.; Fuche, F.J.; Terrasse, R.; Poquet, C.; Havránek, J.; Pignotti, S.; Krawczyk, A.; Arraou, M.; et al. In Situ Targeted Base Editing of Bacteria in the Mouse Gut. Nature 2024, 632, 877–884.