Transferring microbiota from young to aged mice helped to restore molecular signaling necessary for proper intestinal function and improved the regenerative capacity of intestinal stem cells [1].

Everyday companions

Bacteria, viruses, and other microbes are well-known as agents that cause disease and should be avoided. However, the microbes that make us sick, while more noticeable, are in the minority. The majority of microbes are either harmless or beneficial, and we all coexist with millions of them every day. Moreover, we cannot function properly without their assistance. Researchers refer to these microbes as microbiota: microbes that reside both inside and outside the human body and are especially abundant in the intestine.

Microbiota affect multiple aspects of health, including digestion and immune modulation, along with aging processes; aging-related changes in microbiotal composition are associated with age-related conditions such as obesity [2], inflammatory bowel disease [3], and irritable bowel syndrome [4].

The microbiome matters

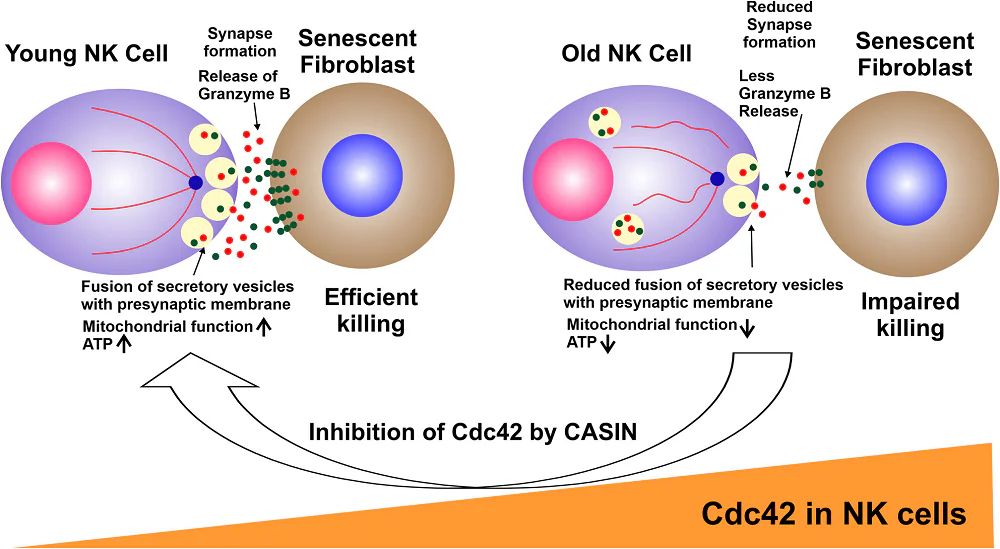

The authors of this study focused on the aging processes in the intestinal epithelium. Aging is associated with reduced intestinal epithelial turnover and a decline in the self-renewal and differentiation abilities of its stem cells. At the molecular level, previous studies have linked this functional decline in intestinal stem cells to reduced canonical Wnt signaling [5].

The researchers began by assessing Wnt gene expression in the intestinal crypts of mice, which are home to these stem cells. Microbiotal abundance was found to affect Wnt signaling, and its removal reduces regenerative capacity after irradiation.

Transferring microbiota

One approach that has the potential to restore age-related changes in microbiotal composition is fecal microbiota transfer. Those researchers performed heterochronic fecal microbial transfers (FMTs), transferring young microbiota to aged animals and aged microbiota to young animals, along with control groups of homochronic control transfers (young microbiota to young animals and aged microbiota to aged animals).

Seven days after this transfer, an analysis suggested that it impacted the composition of the microbiome of the recipient, “with the age clock of the microbiota in the intestine of the recipient animal set to the clock of the FMT donor.”

An analysis of Wnt gene expression found that the control group of young animals that received young microbiota had more expression of Wnt3 and of the canonical Wnt signaling genes Ascl2 and Lgr5, as well as the intestinal stem cell marker gene Olmf4 in crypts, compared to aged animals that received aged microbiota.

When aged animals received young fecal samples, the expression levels of central canonical Wnt signaling genes in aged crypts and intestinal stem cells increased compared to aged animals that received an aged microbiome. Transferring young microbiota to aged animals also improved the function of aged intestinal stem cells, specifically the regeneration of intestinal epithelial tissue.

“This reduced signaling causes a decline in the regenerative potential of aged intestinal stem cells,” said co-author Yi Zheng, PhD, director of the Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology at Cincinnati Children’s. “However, when older microbiota were replaced with younger microbiota, the stem cells resumed producing new intestine tissue as if the cells were younger. This further demonstrates how human health can be affected by the other life forms living inside us.”

Complex interactions

The microbiome contains many species of microbes, and the researchers investigated which of them affect Wnt signaling and intestinal stem cells. To narrow their search, they identified 7 microbial groups whose abundance was affected by both aging and the transfer of young microbiota to aged animals. One of those microbial species was Akkermansia muciniphila, whose abundance was higher in the aged animals that received aged microbiota and young animals that received aged microbiota compared to the young animals that received young microbiota and the aged animals that received young microbiota.

Akkermansia muciniphila’s role in the biology of aging appears complex and ambiguous. On one hand, elevated levels of this bacterium are generally considered beneficial for the intestine [6], and it has been shown to extend the lifespan of progeroid animals, which suffer from accelerated aging [7]. Several studies have also shown enrichment of Akkermansia muciniphila in the guts of healthy, long-lived older adults [8]. However, on the other hand, different reports show that centenarians, who are considered to be ‘successful agers’, have reduced levels of Akkermansia muciniphila [9], suggesting that its impact on aging processes might be negative.

In this study, orally providing more Akkermansia muciniphila to young and aged mice increased its levels in the the first and shortest segment of the small intestine (the duodenum) of aged mice, while levels in young mice were unchanged. The researchers suggest that this is due to insufficient mucin levels in the young intestinal epithelium. Mucin serves as a food source for Akkermansia muciniphila, and mucin levels in young animals may be insufficient to support its abundance; however, this was not tested.

Akkermansia muciniphila negatively impacted the expression levels of canonical Wnt signaling genes in aged animals. In aged mice, following the administration of this bacterium, the researchers observed a further reduction in Ascl2 and Lgr5 gene levels compared to untreated age-matched controls, but only a small change in young mice that received Akkermansia muciniphila. Further experiments also indicated a “reduced regenerative potential of aged intestinal stem cells exposed to A. muciniphila.”

The increased levels of Akkermansia muciniphila in the intestines of aged mice following treatment were accompanied by changes in the levels of other microbes. Researchers hypothesized that it is possible that these other microbes may be partially responsible for the observed changes in intestinal function and gene expression following its administration. However, the changes of other microbiome components and their impact on Wnt signaling and the regenerative capacity of intestinal stem cells were not evaluated in this study.

Despite the lack of mechanistic understanding, this study contributed to the growing body of scientific evidence demonstrating the microbiome’s impact on intestinal aging. As concluded by the corresponding author, Hartmut Geiger, PhD, director of the Institute of Molecular Medicine at Ulm University and former member of the Division of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology at Cincinnati Children’s, “Our findings show that younger microbiota can prompt older intestine to heal faster and function more like younger intestine.”

We would like to ask you a small favor. We are a non-profit foundation, and unlike some other organizations, we have no shareholders and no products to sell you. All our news and educational content is free for everyone to read, but it does mean that we rely on the help of people like you. Every contribution, no matter if it’s big or small, supports independent journalism and sustains our future.

Literature

[1] Nalapareddy, K., Haslam, D. B., Kissmann, A. K., Alenghat, T., Stahl, S., Rosenau, F., Zheng, Y., & Geiger, H. (2026). Microbiota from young mice restore the function of aged ISCs. Stem cell reports, 102788. Advance online publication.

[2] Sun, L., Ma, L., Ma, Y., Zhang, F., Zhao, C., & Nie, Y. (2018). Insights into the role of gut microbiota in obesity: pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic perspectives. Protein & cell, 9(5), 397–403.

[3] Zuo, T., & Ng, S. C. (2018). The Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis and Therapeutics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, 2247.

[4] Theodorou, V., Ait Belgnaoui, A., Agostini, S., & Eutamene, H. (2014). Effect of commensals and probiotics on visceral sensitivity and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut microbes, 5(3), 430–436.

[5] Nalapareddy, K., Nattamai, K. J., Kumar, R. S., Karns, R., Wikenheiser-Brokamp, K. A., Sampson, L. L., Mahe, M. M., Sundaram, N., Yacyshyn, M. B., Yacyshyn, B., Helmrath, M. A., Zheng, Y., & Geiger, H. (2017). Canonical Wnt Signaling Ameliorates Aging of Intestinal Stem Cells. Cell reports, 18(11), 2608–2621.

[6] Naito, Y., Uchiyama, K., & Takagi, T. (2018). A next-generation beneficial microbe: Akkermansia muciniphila. Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition, 63(1), 33–35.

[7] Bárcena, C., Valdés-Mas, R., Mayoral, P., Garabaya, C., Durand, S., Rodríguez, F., Fernández-García, M. T., Salazar, N., Nogacka, A. M., Garatachea, N., Bossut, N., Aprahamian, F., Lucia, A., Kroemer, G., Freije, J. M. P., Quirós, P. M., & López-Otín, C. (2019). Healthspan and lifespan extension by fecal microbiota transplantation into progeroid mice. Nature medicine, 25(8), 1234–1242.

[8] Zeng, S. Y., Liu, Y. F., Liu, J. H., Zeng, Z. L., Xie, H., & Liu, J. H. (2023). Potential Effects of Akkermansia Muciniphila in Aging and Aging-Related Diseases: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Aging and disease, 14(6), 2015–2027.

[9] Wang, F., Yu, T., Huang, G., Cai, D., Liang, X., Su, H., Zhu, Z., Li, D., Yang, Y., Shen, P., Mao, R., Yu, L., Zhao, M., & Li, Q. (2015). Gut Microbiota Community and Its Assembly Associated with Age and Diet in Chinese Centenarians. Journal of microbiology and biotechnology, 25(8), 1195–1204.