Engineered Extracellular Vesicles Reduce Arrhythmia in Rats

- Coating them with platelet membranes had significant benefits.

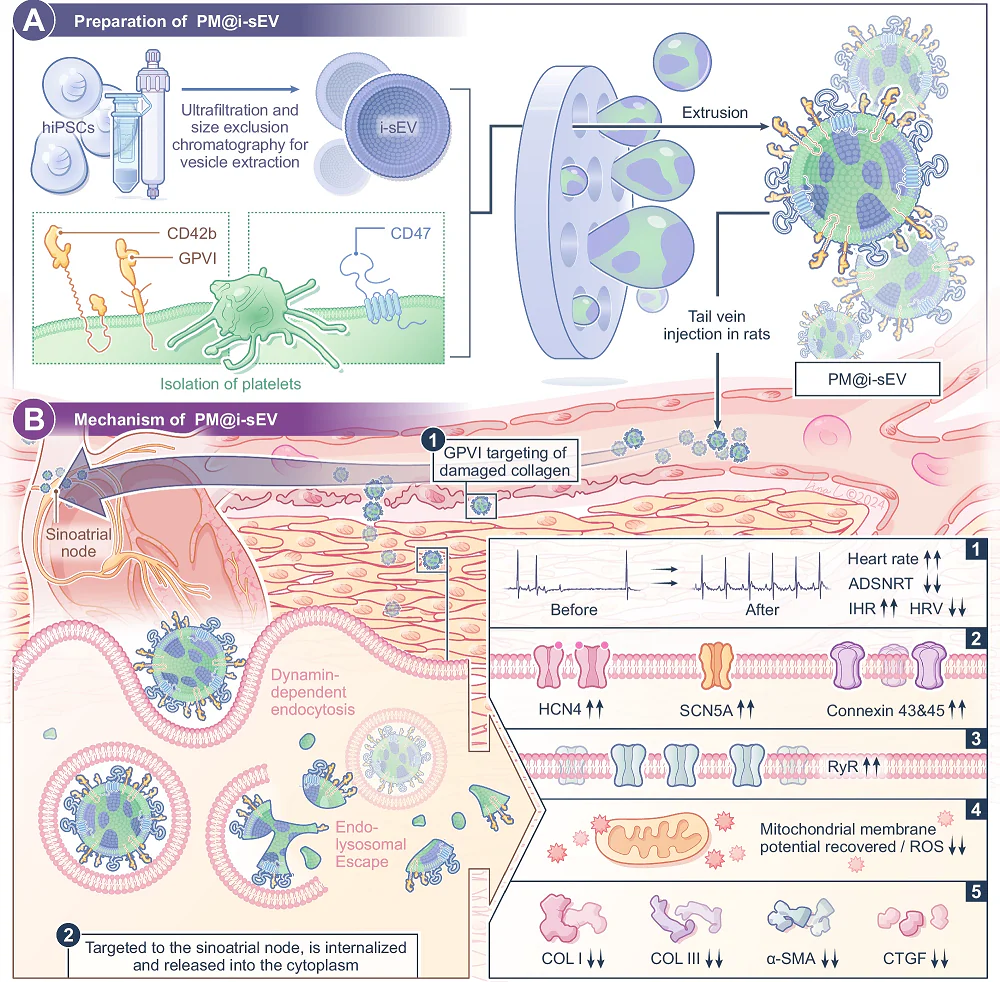

- Combining small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) with plasma membrane proteins created PM@i-sEVs.

- These modified sEVs preferentially go to collagen-rich injured areas and do not accumulate in the liver.

- They were found to contain beneficial microRNAs and reduce arrhythmia in a rat model.

In Nature Communications, researchers have described how small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) fused with plasma membrane proteins successfully treated heart arrhythmia in a rat model.

Why do people need pacemakers?

In a healthy heart, the sinoatrial node (SAN) serves as a natural regulator, commanding the heart to regularly contract. As it becomes dysfunctional and fibrotic with age, heart arrhythmia is the result [1]. Artificial pacemakers are the standard of care for this condition, but such devices come with their own complications [2].

Some work has focused on regenerating the SAN, including turning heart cells into pacemaker cells with gene therapy [3], directly injecting SAN cells created through induced pluripotency [4], and, in some cases, targeting specific ion channels through RNA editing [5]. However, there are inherent risks of cancer and cellular death, and making these interventions into safe, reliable, and broadly applicable therapies has proven to be difficult [6].

An effective delivery method

These researchers, therefore, turned to sEVs as their desired method for bringing protective RNA and proteins to the cells that need them. Ordinary sEVs, however, are quickly recycled in the body and do not naturally target specific cells [7]. Engineering these vesicles, therefore, has become a priority, with multiple techniques being explored [8]. Coating them in platelet membrane proteins serves two key functions: it hides them from the immune system, and it encourages delivery to injured areas [9].

The particular sEVs used in this experiment were derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), filtered by size. Rat platelets were then stripped of their contents and their membranes were attached to the sEVs, creating PM@i-sEVs. The researchers then subjected these modified sEVs to a barrage of tests, confirming that the plasma membrane was securely fastened to the sEV and that the membrane-enclosed sEVs do not congeal together the way that actual platelets do.

PM@i-sEVs were confirmed to be taken up into induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs). 24 hours after they were taken up, they released their contents into the cells’ cytosol. Further testing in rats found that they were found to be better taken up by SAN cells instead of being concentrated in the liver the way that unmodified sEVs are. Further in vitro testing found that they were significantly more attracted to collagen-coated cells than their unmodified counterparts.

Effective in rats

To test the effectiveness of PM@i-sEVs, the researchers created a rat model of heart arrhythmia. The rats’ SANs were injured with sodium hydroxide and ischemia-reperfusion, which was confirmed to induce arrhythmia.

24 andd 72 hours after this injury, some of these rats were injected with PM@i-sEVs, others were injected with i-SEVs, and others served as controls. After a month, the rats treated with PM@i-sEVs fared much better than the other two groups as measured by multiple metrics of heart rhythm function, and there was no damage to other organs as a result of this treatment.

A closer examination found that the treated rats had SANs that were visibly less diseased than those of the other two groups. There was less fibrosis, better collagen deposition, more organized tissue structure, and less congestion; further in vitro experiments found that PM@i-sEVs do indeed significantly reduce fibrosis in cells.

An examination of the specific microRNA molecules found in the sEV payloads suggested potential reasons why. Several of these molecules that were “previously linked to cardiac repair, arrhythmia suppression, and ischemic preconditioning” were found in these vesicles. While this was only an injured rat model and further work needs to be done to confirm these EVs’ effects in naturally aged organisms, including humans, this approach appears to be promising.

Literature

[1] Duan, S., & Du, J. (2023). Sinus node dysfunction and atrial fibrillation—Relationships, clinical phenotypes, new mechanisms, and treatment approaches. Ageing Research Reviews, 86, 101890.

[2] Glikson, M., Nielsen, J. C., Kronborg, M. B., Michowitz, Y., Auricchio, A., Barbash, I. M., … & Witte, K. K. (2022). 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: Developed by the Task Force on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). EP Europace, 24(1), 71-164.

[3] Kapoor, N., Liang, W., Marbán, E., & Cho, H. C. (2013). Direct conversion of quiescent cardiomyocytes to pacemaker cells by expression of Tbx18. Nature biotechnology, 31(1), 54-62.

[4] Protze, S. I., Liu, J., Nussinovitch, U., Ohana, L., Backx, P. H., Gepstein, L., & Keller, G. M. (2017). Sinoatrial node cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent cells function as a biological pacemaker. Nature biotechnology, 35(1), 56-68.

[5] D’Souza, A., Pearman, C. M., Wang, Y., Nakao, S., Logantha, S. J. R., Cox, C., … & Boyett, M. R. (2017). Targeting miR-423-5p reverses exercise training–induced HCN4 channel remodeling and sinus bradycardia. Circulation research, 121(9), 1058-1068.

[6] Vo, Q. D., Nakamura, K., Saito, Y., Iida, T., Yoshida, M., Amioka, N., … & Yuasa, S. (2024). IPSC-derived biological pacemaker—From bench to bedside. Cells, 13(24), 2045.

[7] Rai, A., Claridge, B., Lozano, J., & Greening, D. W. (2024). The discovery of extracellular vesicles and their emergence as a next-generation therapy. Circulation research, 135(1), 198-221.

[8] Fan, M., Zhang, X., Liu, H., Li, L., Wang, F., Luo, L., … & Li, Z. (2024). Reversing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Cardiotoxicity via Bioorthogonal Metabolic Engineering–Driven Extracellular Vesicle Redirecting. Advanced Materials, 36(45), 2412340.

[9] Hu, C. M. J., Fang, R. H., Wang, K. C., Luk, B. T., Thamphiwatana, S., Dehaini, D., … & Zhang, L. (2015). Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature, 526(7571), 118-121.