The Impact of Childbearing Trajectories on Aging

- The number and timing of pregnancies matter.

- According to epigenetic clocks and other data, women who have no children and women who have large numbers of children age more quickly than women who have two or three children.

- Having children earlier in life is also associated with accelerated aging.

- This cohort study could not demonstrate causation, and confounding factors may have been involved.

The authors of a recent study investigated the relationship between reproduction (number and timing of children), aging, and survival. An analysis of seven distinct reproductive trajectories suggested that two groups, women with the most live births and childless women, showed accelerated aging and increased mortality risk [1].

To maintain the body or to reproduce?

“From an evolutionary biology perspective, organisms have limited resources such as time and energy. When a large amount of energy is invested in reproduction, it is taken away from bodily maintenance and repair mechanisms, which could reduce lifespan.” This idea from evolutionary biology, explained by the doctoral researcher Mikaela Hukkanen, who conducted the study, has been under investigation for many years.

Previous studies investigating this theory often focused on a single variable in female reproduction: the number of children. However, childbearing is much more complex than that. Some women have their first child as teenagers, while others wait until their late 30s or even 40s. Some do not have children at all, while others might have ten or more. This study recognized these facts and investigated childbearing’s impact on aging in a more complex way.

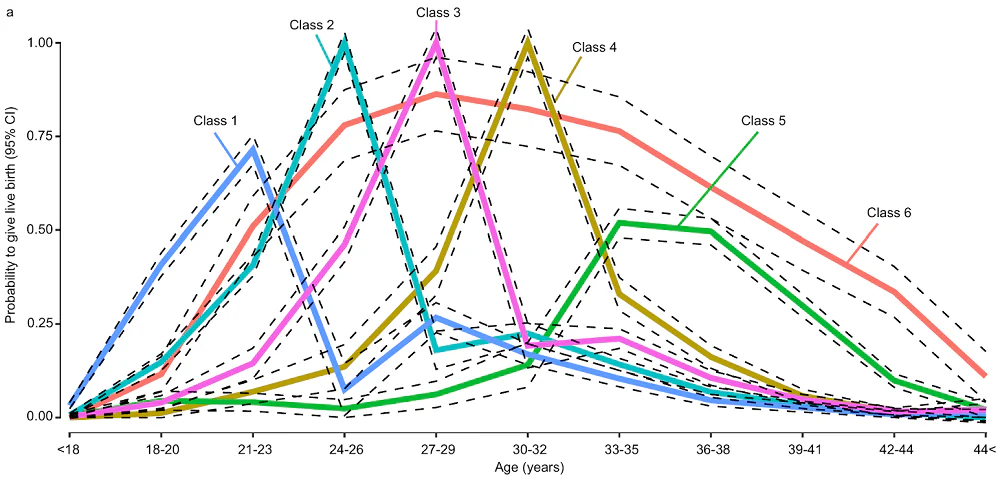

The researchers used data on the timing and number of childbearing events from almost 15,000 women born between the 1880’s and the mid-20th century. This data comes from the Finnish Twin Cohort, a population-based study that also included data on socioeconomic background and lifestyle-related factors. The researchers used advanced modeling techniques to group women based on their childbearing history, and these models suggested seven distinct trajectories (including childlessness).

The biggest risks are at the extremes

After adjusting for different living standards in different time periods, the researchers found distinctions between each class’s survival rate. They observed the greatest increases in risk of death for women with many (6.8 on average) live births throughout life (Class 6) and childless women (Class 0), and these findings were consistent between different models. There was also a somewhat higher risk for women who only had a few live births early in life (Classes 1 and, to a lesser extent, 2) when compared to Class 3, which was used as a reference. The strength of this association weakened but remained significant after adjustment for known risk factors, including BMI, tobacco and alcohol use, and education.

These different childbearing trajectories were also associated with distinct epigenetic aging profiles, which better reflect the impact of childbearing on age acceleration before old age.

First, the authors used GrimAge, an epigenetic clock known for its strong predictive ability for time-to-death and its association with many age-related conditions. According to this clock and DNA methylation data from over 1,000 women, women in class 1 have the most accelerated aging compared to Classes 3, 4, and 5, which include women who gave birth in their late 20s and early 30s.

When the data was adjusted for known risk factors, childless women had more accelerated aging by 1 year compared to class 5, which consisted of females with some of the lowest numbers of children (2 children on average) but had those children rather late in life. However, the largest difference in epigenetic age acceleration (1.35 higher epigenetic aging rate) was between class 6, which consisted of females with the highest number of children, and Class 5. The latter group was epigenetically younger. Class 6 also had the highest rate of aging compared to Class 0 and Classes 2-5 when the same analysis was performed using two different epigenetic clocks.

“A person who is biologically older than their calendar age is at a higher risk of death. Our results show that life history choices leave a lasting biological imprint that can be measured long before old age,” says the study lead, Dr. Miina Ollikainen.

“In some of our analyses, having a child at a young age was also associated with biological aging. This too may relate to evolutionary theory, as natural selection may favor earlier reproduction that entails shorter overall generation times, even if it entails health-related costs associated with aging.”

The connection between early motherhood, the pace of aging, and survival can also be driven by limited access to healthcare and resources and a generally worse socioeconomic situation, all of which lead to higher physical, emotional, and economic stress loads in young mothers; however, this study didn’t directly investigate this.

U-shaped pattern

The researchers summarized that the patterns they observed, especially increased mortality risk and accelerated aging among childless women and those with a high number of children, are in line with previous studies that reported a U-shaped relationship between the number of children and health [2-5].

The findings regarding the high number of children might not be surprising, since childbearing requires significant resources, tilting the balance away from body maintenance towards reproduction. However, the opposite might be expected of childless women, whose resources should be devoted entirely to body maintenance, thus suggesting a longer lifespan, but the results suggest a higher mortality risk and accelerated aging in this group.

Such an observation was previously explained by pre-existing risk factors that negatively affected reproduction. Those same factors might accelerate aging and increase mortality risk in those women. However, in this study, the association between increased mortality risk and accelerated aging among childless women is significant even after adjusting for risk factors, suggesting that such pre-existing risk factors cannot fully explain the effect on lifespan and healthspan and “that childbearing history itself may have a direct effect on survival and age acceleration.” The authors suggest that childless women might suffer those higher risks and accelerated aging due to a lack of pregnancy and lactation’s protective effects on certain diseases as well as a lack of social support from children.

On average, the women who aged the slowest gave birth to 2-2.4 children and had their children when they were around 27 years old, with 24 and a half years and almost 30 years for first and last childbirth. However, differences in survival and aging profiles between different classes are rather modest, which suggests “reproductive timing and number of offspring may have a smaller impact on aging and survival than we initially expected.”

The researchers underscore that those results are based on this specific sample and are not only driven by biological parameters but also by socioeconomic and cultural effects. While they support the idea of balancing resources between offspring and body maintenance, this study can only indicate associations, not causal effects. Additionally, the researchers caution that they do not suggest any reproductive choices on the individual level, as this study focuses on population-level observations. “An individual woman should therefore not consider changing her own plans or wishes regarding children based on these findings,” said the study lead, Dr. Miina Ollikainen.

Literature

[1] Hukkanen, M., Kankaanpää, A., Heikkinen, A., Kaprio, J., Cristofari, R., & Ollikainen, M. (2026). Epigenetic aging and lifespan reflect reproductive history in the Finnish Twin Cohort. Nature communications, 17(1), 44.

[2] Long, E., & Zhang, J. (2023). Evidence for the role of selection for reproductively advantageous alleles in human aging. Science advances, 9(49), eadh4990.

[3] Wang, X., Byars, S. G., & Stearns, S. C. (2013). Genetic links between post-reproductive lifespan and family size in Framingham. Evolution, medicine, and public health, 2013(1), 241–253.

[4] Grundy, E., & Tomassini, C. (2005). Fertility history and health in later life: a record linkage study in England and Wales. Social science & medicine (1982), 61(1), 217–228.

[5] Keenan, K., & Grundy, E. (2018). Fertility History and Physical and Mental Health Changes in European Older Adults. European journal of population = Revue europeenne de demographie, 35(3), 459–485.