Discovering Why an Inflammatory Compound Inhibits Cancer

- This compound can do different things depending on how it's processed.

In Aging Cell, researchers have published their findings into why the inflammatory factor IL-6 inhibits cancerous tumors when generated inside the cell.

IL-6 affects both senescence and cancer proliferation

Read More

One of the core parts of the SASP is the inflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6). While this factor is a key aspect of the age-related chronic inflammation known as inflammaging, it also fights against cancer: a phenomenon known as oncogene-induced senescence, in which cells become senescent before they can become cancerous [1], is characterized by an increased expression of IL-6 among other factors [2].

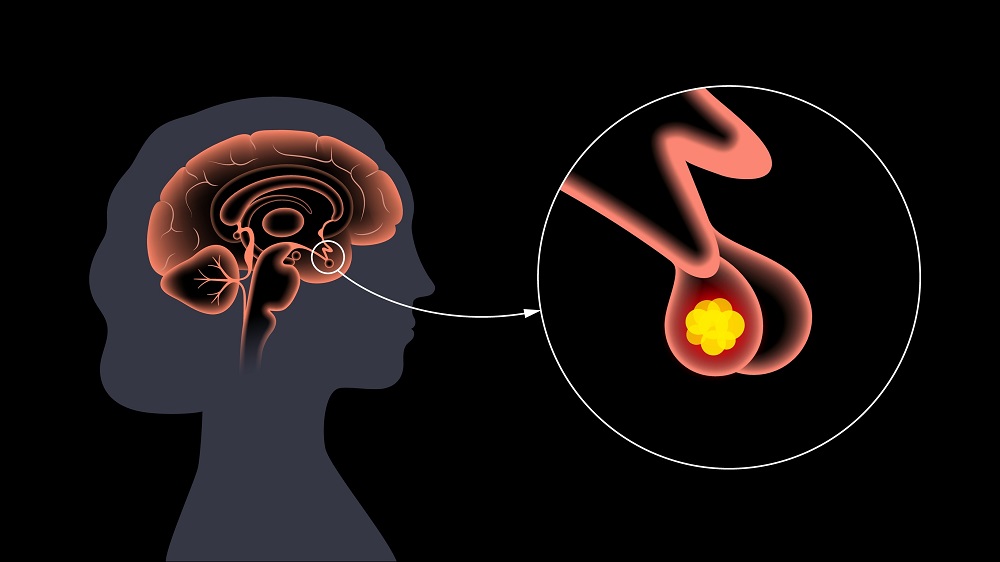

An unusual phenomenon is visible in the pituitary gland, however. There, IL-6 stimulates cell growth [3], and cancers of the pituitary gland are encouraged to proliferate in the presence of IL-6 outside the cell [4]; however, IL-6 from inside the cell encourages these cells to become senescent instead [5]. Similarly contradictory effects were seen in melanoma as well, with IL-6 signals from outside the cell promoting proliferation while internal IL-6 encourages senesence [6].

These perplexing facts led the researchers of this study to engage in a more in-depth biological study, carefully examining some of the pathways and networks involved in IL-6 to determine why this is the case.

Finding the pathway

In their first experiment, the researchers took cancerous pituitary gland cells from rats, then inhibited their ability to secrete factors into the outside environment with the compound BFA. This encouraged the buildup of internal IL-6 instead, and this buildup led to well-known factors associated with cellular senescence, such as SA-β-gal and p16. A second method of accomplishing this, blocking the Rab11 pathway, led to similar results. The researchers also confirmed that this had nothing to do with the process of bringing IL-6 into the cell: instead, IL-6 generated inside the cell was driving senescence.

Whether or not they had their secretion inhibited, pituitary tumor cells had problems with the nuclear lamina, which is associated with senescence. This lack of nuclear cohesion leads to DNA fragments floating around in the cell, and this type of damage is sensed by the STING pathway, which is also associated with senescence.

The BFA-treated tumor cells had the same amount of STING, but it was more diffused throughout the cell. Inhibiting STING decreased the senescence-related effects of BFA and decreased the senescence-related factor NFκB as well. The researchers found that the pathway between IL-6 and NFκB was responsible for the increase in cellular senesence.

Living animals and human cells

The researchers then performed a mouse experiment, injecting immunodeficient mice with either wild-type pituitary tumor cells, one of two modified pituitary tumor cell lines that produced no IL-6, or a pituitary tumor cell line that produced very little IL-6. The wild-type cells did not form tumors in these mice, but the cells without IL-6 proliferated rapidly, forming tumors in a week; the group that produced very little IL-6 took 20 days to do so.

Similar results were found for human cells. Human lung cancer cells were treated with doxocirubin that drove them senescent, causing the proliferation of IL-6 within these cells. The receptor for receiving IL-6 from outside the cells played no part in this senescence.

While the researchers did not discover why IL-6 from outside the cell can lead to tumor proliferation, they note that their research warrants caution in the development of senomorphic or other anti-senescence drugs that inhibit cellular production of IL-6. Reducing cellular senescence is normally a good thing, but not when it leads to cancer instead.

Literature

[1] Collado, M., Gil, J., Efeyan, A., Guerra, C., Schuhmacher, A. J., Barradas, M., … & Serrano, M. (2005). Senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature, 436(7051), 642-642.

[2] Coppé, J. P., Desprez, P. Y., Krtolica, A., & Campisi, J. (2010). The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annual review of pathology: mechanisms of disease, 5(1), 99-118.

[3] Graciarena, M., Carbia-Nagashima, A., Onofri, C., Perez-Castro, C., Giacomini, D., Renner, U., … & Arzt, E. (2004). Involvement of the gp130 cytokine transducer in MtT/S pituitary somatotroph tumour development in an autocrine-paracrine model. European journal of endocrinology, 151(5), 595-604.

[4] Jones, T. H., Daniels, M., James, R. A., Justice, S. K., McCorkle, R., Price, A., … & Weetman, A. P. (1994). Production of bioactive and immunoreactive interleukin-6 (IL-6) and expression of IL-6 messenger ribonucleic acid by human pituitary adenomas. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 78(1), 180-187.

[5] Sapochnik, M., Haedo, M. R., Fuertes, M., Ajler, P., Carrizo, G., Cervio, A., … & Arzt, E. (2017). Autocrine IL-6 mediates pituitary tumor senescence. Oncotarget, 8(3), 4690.

[6] Kuilman, T., Michaloglou, C., Vredeveld, L. C., Douma, S., van Doorn, R., Desmet, C. J., … & Peeper, D. S. (2008). Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell, 133(6), 1019-1031.