Recombinant Human Protein Stops Neuronal Loss in Alzheimer’s

- The drug works in animal models and in humans.

- UCH-L1, NfL, and GFAB are three proteins that are useful in diagnosing brain health.

- They were used to assess the efficacy of sargramostim in animals and humans with Alzheimer’s disease.

A recent study investigated biomarkers that can help monitor trajectories of Alzheimer’s disease-related molecular processes, such as neuronal cell death, and how patients respond to treatments. The authors reported that using biomarkers enabled them to gain insights into the molecular processes that contribute to improved cognition following human recombinant granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, sargramostim) treatment [1].

Measuring the damage

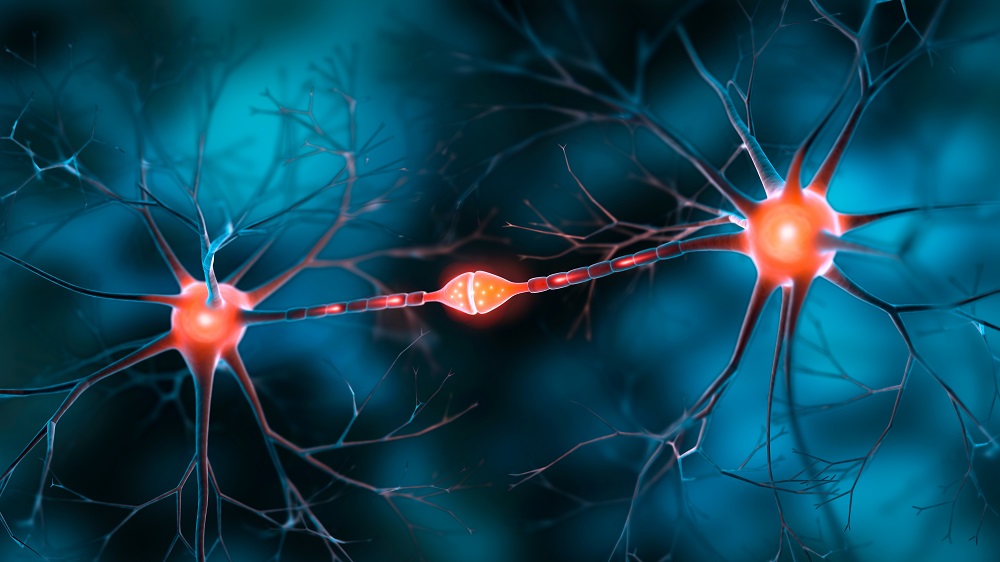

Alzheimer’s disease is accompanied by neuronal loss and increased inflammation [2, 3]. However, to monitor those processes, whether for diagnostic purposes or to aid in the development of Alzheimer’s disease therapies, easy-to-measure blood biomarkers are indispensable.

The authors of this study investigated such biomarkers. They focused on three proteins: ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) for neuronal cell loss, neurofilament light (NfL) for neuron and axon damage, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) for astrogliosis (an abnormally high number of astrocytes in response to neuronal destruction) and inflammation.

Changes in the healthy population

The researchers assessed the levels of UCH-L1, NfL, and GFAB in 317 healthy participants aged 2 to 85. Plasma UCH-L1 and NfL concentrations grew exponentially from ages 2 to 85. However, there were some differences between the two markers. For UCH-L1, the rate of exponential increase in females is faster than in males. For NfL, the estimated change per year is greater than that of UCH-L1, and the rate of exponential increase in females is slower than in males (opposite to that of UCH-L1).

Such an exponential age-dependent increase in neuronal damage markers suggests that brain aging is a lifelong process; however, its effects are evident in older age, “as the accumulated neuronal damage overcomes neurogenesis, functional redundancy, and resiliency in some individuals but not all.”

GFAP showed a different type of relationship with age. GFAP levels remain relatively constant up to 25, and around 40, they start to rise exponentially. As with previous markers, there are sex-specific differences, with females showing higher GFAP plasma levels across all ages.

It appears that plasma biomarkers of neuronal damage, UCH-L1 and NfL, increase earlier in life than the astrogliosis marker (GFAP), suggesting that astrogliosis and inflammation are responses to age-related neuronal damage.

Alzheimer’s disease trajectories

Once the trajectories of plasma markers of neurodegeneration (UCH-L1 and NfL) and of astrogliosis and inflammation (GFAP) in healthy individuals throughout their lifespan were established, the researchers compared them with those observed in 36 people with Alzheimer’s disease and 32 patients with mild cognitive impairment.

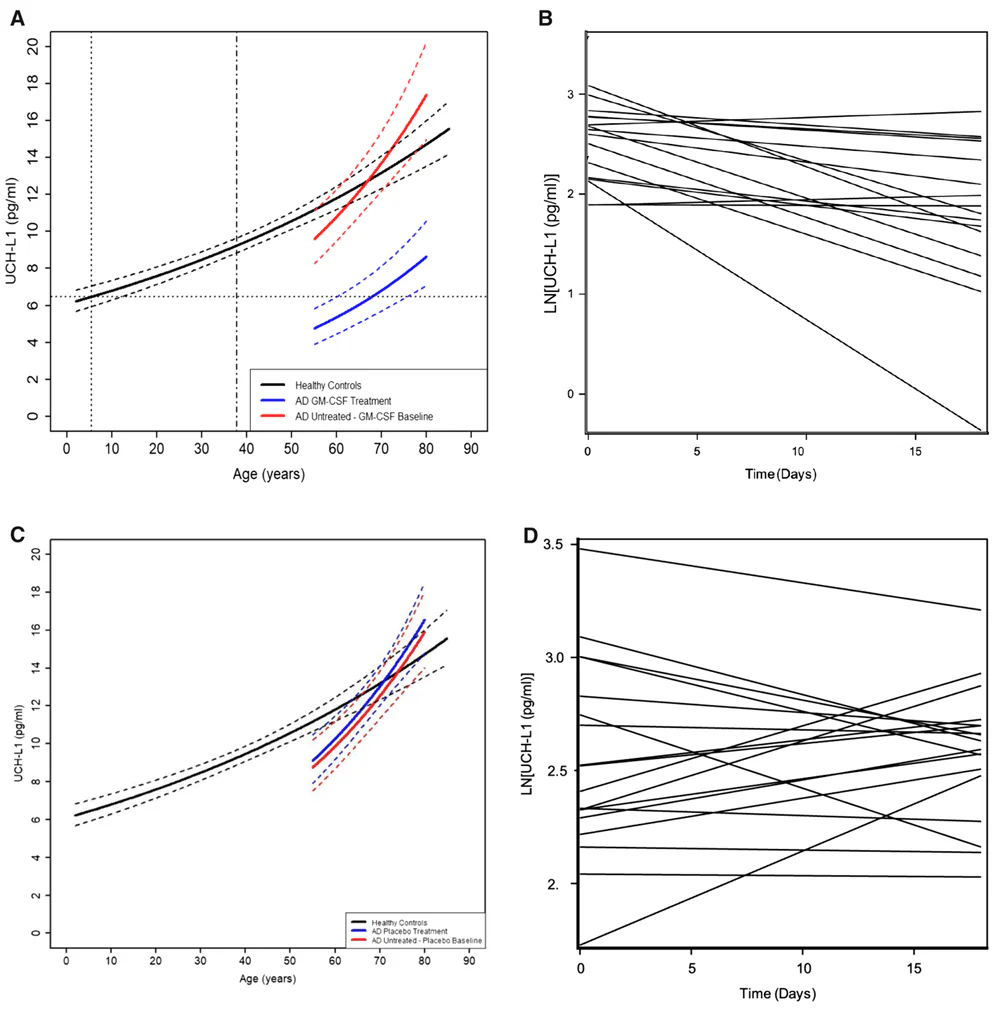

Patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease had higher levels of NfL and GFAP compared to healthy controls of the same age. The same was true for UCH-L1 levels in plasma from participants with mild cognitive impairment, but in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease, UCH-L1 levels in plasma were comparable to those of healthy participants of the same age.

Efficacy

The biomarkers investigated in this study can provide a better understanding of the mechanisms and trajectories of brain aging and help assess the efficacy of interventions aimed at slowing brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

The researchers used their previous study to evaluate the usefulness of those biomarkers in testing the efficacy of Alzheimer’s disease treatment, specifically using the immune-system-modulating cytokine GM-CSF, a long-approved drug that has also been investigated in the treatment of many other neurological injuries and diseases, including age-related cognitive decline, Down syndrome, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and Parkinson’s disease [4-8].

Treatment of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with GM-CSF “reverses cognitive decline and the rate of neuron death after just a few weeks of treatment,” said the study’s senior author, Professor Huntington Potter, PhD, director of the University of Colorado Alzheimer’s and Cognition Center at CU Anschutz. The benefits of GM-CSF extend beyond Alzheimer’s disease and also benefit normal brain aging, as it improves impaired cognition and reduces neuronal function in aged wild-type mice [9].

The benefits are not limited to mice. These researchers conducted a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of human recombinant GM-CSF (sargramostim) in people suffering from mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease [10]. “This drug improved one measure of cognition and reduced a blood measure of neuron death in people with AD in a relatively short period of time in its first clinical trial,” Potter said.

However, one of the most significant improvements was observed in the plasma UCH-L1 concentrations. “When people with AD were given sargramostim in the clinical trial, their blood levels of the UCH-L1 measure of neuronal cell death dropped by 40% – in our study, this was similar to levels seen in early life,” Potter said. “We were very surprised.”

Given the high sensitivity of UCH-L1 to sargramostim/GM-CSF, this biomarker might be a good candidate for assessing the efficacy of many Alzheimer’s disease treatments, including lifestyle changes.

NfL and GFAP were not reduced. The most likely reason is the very short treatment period (only 3 weeks) and the short plasma half-life of UCH-L1 relative to NfL and GFAP.

Understanding the mechanism

An aged rat model of Alzheimer’s disease helped to understand the mechanism behind GM-CSF treatment’s effects on caspase-3, a marker of cellular death by apoptosis. The number of caspase-3-positive cells is increased in humans and animal models with Alzheimer’s disease, and this was also evident in the aged Alzheimer’s disease rats used in this experiment, specifically in hippocampal neurons. GM-CSF treatment significantly reduced those numbers to levels comparable to those of wild-type untreated animals, suggesting that GM-CSF reduces neuronal cell death. Assessment of GFAP staining showed that GM-CSF treatment also reverses astrogliosis in some hippocampal regions of the Alzheimer’s disease rat model.

Those results suggest that the beneficial effects of GM-CSF treatment on cognition and various biomarkers are “likely due to a reduction in the number of apoptotic neurons in the brain.” The authors also add that since the GM-CSF can stimulate some of the immune cells, it can also contribute to “removal of damaged, apoptotic, and senescent neurons, thus allowing the remaining neurons to function more effectively.”

Informative biomarkers

Potter summarized, “These findings suggest that the exponentially higher levels of these markers with age, likely accelerated by neuroinflammation, may underlie the contribution of aging to cognitive decline and AD and that sargramostim treatment may halt this trajectory.”

Additionally, using those markers, the researchers can identify people with mild cognitive impairment, suggesting they may be used to predict future Alzheimer’s disease. However, variability in marker levels indicates that other players also influence the risk of developing the disease, and factors such as genetics or lifestyle can shape the trajectory of cognitive decline.

Literature

[1] Sillau, S. H., Coughlan, C., Ahmed, M. M., Nair, K., Araya, P., Galbraith, M. D., Ritchie, A., Ching-Jung Wang, A., Elos, M. T., Bettcher, B. M., Espinosa, J. M., Chial, H. J., Epperson, N., Boyd, T. D., & Potter, H. (2025). Blood measure of neuronal death is exponentially higher with age, especially in females, and halted in Alzheimer’s disease by GM-CSF treatment. Cell reports. Medicine, 102525. Advance online publication.

[2] Risacher, S. L., Anderson, W. H., Charil, A., Castelluccio, P. F., Shcherbinin, S., Saykin, A. J., Schwarz, A. J., & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2017). Alzheimer disease brain atrophy subtypes are associated with cognition and rate of decline. Neurology, 89(21), 2176–2186.

[3] Hyman, B. T., Van Hoesen, G. W., Damasio, A. R., & Barnes, C. L. (1984). Alzheimer’s disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science (New York, N.Y.), 225(4667), 1168–1170.

[4] Kim, N. K., Choi, B. H., Huang, X., Snyder, B. J., Bukhari, S., Kong, T. H., Park, H., Park, H. C., Park, S. R., & Ha, Y. (2009). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes survival of dopaminergic neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced murine Parkinson’s disease model. The European journal of neuroscience, 29(5), 891–900.

[5] Kelso, M. L., Elliott, B. R., Haverland, N. A., Mosley, R. L., & Gendelman, H. E. (2015). Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor exerts protective and immunomodulatory effects in cortical trauma. Journal of neuroimmunology, 278, 162–173.

[6] Kong, T., Choi, J. K., Park, H., Choi, B. H., Snyder, B. J., Bukhari, S., Kim, N. K., Huang, X., Park, S. R., Park, H. C., & Ha, Y. (2009). Reduction in programmed cell death and improvement in functional outcome of transient focal cerebral ischemia after administration of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in rats. Laboratory investigation. Journal of neurosurgery, 111(1), 155–163.

[7] Schneider, U. C., Schilling, L., Schroeck, H., Nebe, C. T., Vajkoczy, P., & Woitzik, J. (2007). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced vessel growth restores cerebral blood supply after bilateral carotid artery occlusion. Stroke, 38(4), 1320–1328.

[8] Olson, K. E., Abdelmoaty, M. M., Namminga, K. L., Lu, Y., Obaro, H., Santamaria, P., Mosley, R. L., & Gendelman, H. E. (2023). An open-label multiyear study of sargramostim-treated Parkinson’s disease patients examining drug safety, tolerability, and immune biomarkers from limited case numbers. Translational neurodegeneration, 12(1), 26.

[9] Boyd, T. D., Bennett, S. P., Mori, T., Governatori, N., Runfeldt, M., Norden, M., Padmanabhan, J., Neame, P., Wefes, I., Sanchez-Ramos, J., Arendash, G. W., & Potter, H. (2010). GM-CSF upregulated in rheumatoid arthritis reverses cognitive impairment and amyloidosis in Alzheimer mice. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD, 21(2), 507–518.

[10] Potter, H., Woodcock, J. H., Boyd, T. D., Coughlan, C. M., O’Shaughnessy, J. R., Borges, M. T., Thaker, A. A., Raj, B. A., Adamszuk, K., Scott, D., Adame, V., Anton, P., Chial, H. J., Gray, H., Daniels, J., Stocker, M. E., & Sillau, S. H. (2021). Safety and efficacy of sargramostim (GM-CSF) in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia (New York, N. Y.), 7(1), e12158.