Cellular reprogramming is one of the technologies most associated with longevity. The field was created in 2006, when Shinya Yamanaka showed that a cocktail of four transcription factors, commonly known as OSKM, can cause de-differentiation and massive rejuvenation of a cell, creating an iPSC (induced pluripotent stem cell). About a decade later, partial reprogramming was demonstrated in vivo, where a more subtle application of the factors led to rejuvenation without compromising the cell’s identity.

Today, this field is maturing quickly, with its first clinical trials just around the corner. Academic teams and companies are working on dozens of directions and applications. We asked four experts, all involved in reprogramming-related biotech companies, to talk about their companies’ approaches and the opportunities and bottlenecks that the field faces and to offer predictions for the near and not-so-near future.

What do you find most compelling about cellular reprogramming, and what convinced you it was worth pursuing seriously?

Vittorio Sebastiano, Associate Professor of OBGyN, Stanford, Founder and Scientific Advisory Board Chair at Turn Biotechnologies

What I find most compelling about cellular reprogramming is that it revealed aging to be, at least in part, an actively maintained biological state rather than irreversible accumulation of damage. The discovery that somatic cells retain a latent capacity to reset their epigenetic and functional identity fundamentally changed how we think about cellular plasticity, identity, and time.

For me, the decisive moment was the realization that reprogramming is not merely a tool for generating pluripotent cells, but a window into the mechanisms that establish and stabilize cellular age. Once it became clear that transient or partial reprogramming could decouple rejuvenation from loss of identity, the field shifted from something conceptually fascinating to something therapeutically plausible.

At that point, it was no longer just a powerful biological phenomenon. It became a potential platform for intervention across a wide range of age-associated diseases. The combination of deep mechanistic insight, broad applicability, and the possibility of durable functional restoration made it clear that this was worth pursuing with real rigor and long-term commitment.

Joe Betts-Lacroix, CEO, Retro Biosciences

What I find most compelling about cellular reprogramming is how clearly it shows that aging isn’t just wear and tear. When you can take an old cell and push it back toward a younger functional state, you’re seeing evidence that much of aging is driven by regulatory programs that can be modulated.

What convinced me it was worth pursuing seriously was how strong the effects were. Partial reprogramming doesn’t produce small, ambiguous signals. In well-designed experiments, you see large shifts in gene expression and cellular function, while cells keep their identity. That combination is rare in biology and hard to dismiss.

The other piece was translation. This isn’t just an elegant idea. If cellular state can be reset in a controlled way, it creates a path to treating diseases where aging itself is the dominant risk factor. That’s when reprogramming stopped feeling speculative to me and started to look like a real foundation for medicine.

Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson, SCO, Life Biosciences

What I find most compelling about partial epigenetic reprogramming is that it targets a root cause of aging, the progressive erosion of youthful epigenetic information, rather than just managing downstream symptoms in individual diseases. As someone who has spent decades advancing neuroscience and aging‑related therapies through the clinic, the preclinical data showing that OSK‑based reprogramming can restore function in aged tissues, including in the eye and liver, convinced me this was a modality worth pursuing with the same rigor we apply to traditional therapeutics.

One of our co-founders, David Sinclair, showed that controlled expression of three transcription factors, OCT-4, SOX-2, and KLF-4, or OSK, could reverse retinal aging and restore vision in animal models without losing cell identity. Seeing those findings replicated and extended into non‑human primate models of optic neuropathy, with measurable recovery of visual function, provided exactly the kind of robust, translatable signal that my prior pharma experience has taught me to look for before committing to a new platform.

Yuri Deigin, Co-Founder and CEO, YouthBio

What I find most compelling is that partial reprogramming works via epigenetic mechanisms and I think the epigenome is the closest thing biology has to a writable operating system that dictates cellular age — a view I’ve argued for publicly in my Strong Epigenetic Theory of Aging. In essence, partial reprogramming looks like a controlled way to rewind gene regulation toward a more youthful state without changing cell identity.

What made it even more compelling is that biology already performs rejuvenation naturally after fertilization, but epigenetic clock data suggest that biological age isn’t reset right at fertilization; instead, it declines during early development and reaches a minimum around gastrulation, implying an active, staged program. That offers a plausible reason OSKM is such a powerful lever: it may be reactivating parts of the early-embryo reset machinery — the same kind of transcriptional and chromatin reconfiguration that helps ensure every baby is born young.

I was convinced as soon as I read the 2016 Ocampo et al. paper — that’s why I founded Youthereum back in 2017 to translate partial reprogramming ASAP. Alas, the journey has been slower than I hoped, but I am still bullish on the transformative potential of partial reprogramming.

How is your company unique in the reprogramming landscape – what is your technical approach, and why was it chosen? Please also address safety.

Vittorio Sebastiano

Our company is built around the idea that reprogramming should be treated as a safe precision intervention, not a blunt reset. Our approach focuses on tightly controlled, lineage-preserving rejuvenation driven by defined molecular programs engaged by delivery of reprogramming factors as mRNAs. We selected this strategy because it is the safest, the most tunable and controllable approach to restore youthful function while maintaining tissue architecture and physiological integration.

From the beginning, safety has been a central design constraint rather than an afterthought. We prioritize transient, reversible modalities, strict temporal control, and delivery strategies that minimize systemic exposure. We also invest heavily in orthogonal readouts of safety, including genomic stability, epigenetic integrity, and long-term functional behavior in relevant human cell models.

Importantly, we do not assume that rejuvenation is universally beneficial. Context matters, and different tissues require different degrees and modes of intervention. This philosophy has led us to favor approaches that are tunable, measurable, and grounded in human biology rather than extrapolated from extreme states in animal models.

Joe Betts-Lacroix

Retro is different because we’re very selective about how and where we use reprogramming. The field has shown that cellular age can be reset. The hard part is turning that insight into something that actually works as a therapy.

Our technical approach is to presently focus on specific cell therapy programs where reprogramming can plausibly deliver a large benefit. In our case, that means reprogramming cells outside the body and then introducing their differentiated products back as a cell replacement therapy. This approach is sometimes called full reprogramming, with the huge benefit of providing essentially 100% rejuvenation. It involves canonical iPSC generation. It allows for much tighter control over cell state, identity, and quality before anything reaches a patient, but it’s also inherently limited to cell types that can be removed, reprogrammed, and safely reintroduced.

There is also growing interest in partial reprogramming (PR), which may be done directly inside the body. This approach is exciting because, in principle, it could be applied to a much broader range of cell types directly in vivo. At the same time, it’s less mature from a clinical and safety perspective – because in this scenario, the interventions are directly delivered in the body as gene therapies; they’re harder to control and harder to fully characterize today.

We are exploring in vivo PR as an early discovery effort, but we’re very deliberate about how we do that. As with everything we work on, any progress there will be gated by stringent assessments of safety and efficacy as the programs move through successive stages of development.

We also use AI in ways that accelerate how we explore reprogramming biology. In collaboration with OpenAI, we developed and applied a custom GPT model to help design new variants of the Yamanaka factors. In lab studies, those engineered proteins showed much higher expression of key reprogramming markers compared to the standard factors, expanding the set of tools our scientists can use as we work toward therapies.

Importantly, safety drives how we work. Before anything moves toward the clinic, our teams do extensive preclinical work, starting with in vitro proof of concept, then in vivo proof of concept, followed by the full set of studies required to meet stringent regulatory standards. Reprogramming is powerful biology, and it needs to be handled with care.

At a higher level, we approach this like serious drug development. We narrow the problem, generate strong evidence, and move forward only when the data support it. While we are interested in pushing the biology as far as possible, we also have to stay focused on building therapies that clinicians, regulators, and patients can have confidence in.

Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson

Life Biosciences focuses specifically on partial epigenetic reprogramming using OSK. Partial epigenetic reprogramming allows for a reversal of age/injury degradations of the epigenetic code without a reset of cells to a stem-like state. Our lead program, ER‑100, is designed to rejuvenate cells by resetting the epigenetic code to a younger, healthier state, while preserving their cell identity, enabling cells to function more like their younger counterparts.

In non‑human primate studies, we have demonstrated that intravitreal administration of ER-100 enables expression of OSK in targeted retinal regions, a reset of the epigenetic code to a non-injured profile (DNA methylation patterns), and improvements in visual function. Our GLP-toxicology studies were designed and completed in consultation with the FDA to assess the safety of ER-100 in non-human primates and to confirm a safety profile appropriate for human testing. As an additional safety control, we are using a dual-vector system that allows for OSK to be turned on or off. Our first‑in‑human Phase 1 study in optic neuropathies (including glaucoma and NAION) includes careful safety, tolerability, and immunologic monitoring.

Yuri Deigin

At YouthBio, we realized from day one that partial reprogramming has to be tissue-specific and tightly controllable. Our ultimate goal is systemic rejuvenation, but we think the most realistic way to get there is via a bottom-up approach: go organ by organ — and, when necessary, cell type by cell type — until you can start combining the “winners.” Our intuition tells us that the first meaningful combination therapy will target the 20% of organs that drive 80% of systemic aging, and we’re starting with the organ we think matters most: the brain.

The brain is also a great starting point from a safety standpoint. Neurons are highly resistant to dedifferentiation compared to many proliferative tissues, which gives us a larger safety window than you’d have in something like the liver. Within the brain, Alzheimer’s is an obvious first indication: the unmet need is massive, the standard of care is still limited, and the number of patients is growing quickly.

Technically, our approach is a brain-targeted, inducible OSKM gene therapy, delivered locally to relevant regions (for example, the hippocampus in AD) so we can maximize on-target exposure and minimize systemic risk. Safety is the central concern in this field, so we treat it as the top design constraint. Our next step is IND-enabling safety studies to stress-test the approach before taking it into human Alzheimer’s patients.

What is your strategy for bringing your therapy to the clinic, including target indications and work with partners and regulators?

Vittorio Sebastiano

Our clinical strategy is indication-driven rather than platform-driven. We are prioritizing diseases where aging is a primary driver of pathology, where there is a clear unmet medical need, and where reprogramming-based rejuvenation offers a mechanistically distinct advantage over existing therapies. Early indications are selected to balance biological tractability, clinical relevance, and regulatory clarity.

From the outset, we engage with regulators to align on safety expectations, appropriate biomarkers, and trial design, recognizing that reprogramming challenges traditional categories of therapeutics. We place particular emphasis on demonstrating durable functional benefits rather than short-term molecular changes alone.

Partnerships play a critical role, especially in areas such as delivery, manufacturing, and clinical development, where established expertise can accelerate progress without compromising scientific rigor. Our goal is not to rush reprogramming into the clinic prematurely, but to build a credible path that regulators, clinicians, and patients can trust. I believe we should set a high bar for the entire field rather than cutting corners to be first.

Joe Betts-Lacroix

Our plan for getting therapies into the clinic is shaped by how the regulatory system actually works today. Aging isn’t an indication regulators recognize, so we can’t run a trial just to treat aging. To move forward, we have to demonstrate safety and efficacy in specific diseases, working within the existing framework.

That’s why we use stepping-stone indications. We focus on conditions with clear unmet medical need where the same underlying reprogramming mechanisms can produce meaningful benefits. Those programs let us test the biology in a serious clinical context and generate the kind of evidence regulators expect. Because our lead programs are ex vivo cell therapies, we can generate manufacturing, safety, and characterization data that regulators are already accustomed to reviewing, which makes this a practical place to start.

Partnerships are an important part of that strategy. For example, we’ve licensed foundational intellectual property from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute covering iPSC to hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation, and we collaborate closely with the academic groups that developed key parts of the underlying biology.

We’ve also started engaging with regulators early. Our first engagement with the FDA was an INTERACT meeting for our HSC replacement program, which is a cell therapy aimed at replacing diseased (and ultimately aged) HSCs in the bone marrow to restore immune function. An INTERACT meeting is an early discussion designed to get feedback on a novel therapeutic approach, including preclinical plans, manufacturing considerations, and what the agency will want to see before an IND.

That conversation was constructive and gave us practical guidance. It helped shape the HSC program and also informed how we think about our microglia replacement program. More broadly, it reinforced our view that reprogramming will reach patients by building confidence step by step, using real data, in real disease settings.

Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson

Our clinical strategy starts with areas where the biology, delivery, and unmet need align with the serious global impact of aging-related disease. Beginning with optic neuropathies, in which loss of retinal ganglion cells leads to permanent vision impairment, ER‑100 is being developed initially for primary open‑angle glaucoma and non‑arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), where there are no approved therapies that can reverse or prevent vision loss and where the eye offers a relatively contained, well‑characterized organ for first‑in‑human testing.

The Phase 1 trial cleared for initiation by the FDA in January is designed to evaluate safety, tolerability, immune responses, and multiple visual function endpoints in patients with these conditions, with the goal of building a rigorous, data‑driven foundation for subsequent dose selection and Phase 2 design. From my experiences leading programs from discovery through Phase 2B clinical trials and leading translational efforts over a greater than 30-year career, we are intentional about translational endpoints, trial design, and patient selection so that each study meaningfully de‑risks the next step.

On the partnership and regulatory side, we see ourselves as part of a broader ecosystem that defines what reprogramming-based therapies look like in the clinic. We prioritize engaging with regulators to align on clinical requirements, trial design, and safety monitoring for a first‑in‑class modality, and we collaborate with academic and clinical partners who bring deep expertise in ophthalmology, regenerative medicine, and aging biology. Over time, as the platform matures, we expect to expand to additional indications, informed in part by the promising initial preclinical data we are seeing in liver diseases such as MASH.

Yuri Deigin

We’re taking a very conventional, tried-and-true path to the clinic. Long-term, we would love global approval, but we are starting with the U.S. and building the program around FDA expectations from the beginning, with Alzheimer’s as our lead indication.

A big part of our strategy is to engage regulators early and make sure we’re solving the right problems in the right order. We had a positive FDA INTERACT meeting a few months ago, and the next major step is IND-enabling work — especially safety studies designed to stress-test controllability, biodistribution, and longer-term tolerability — so that when we go into humans, we’re doing it with the strongest possible safety foundation.

How close do you think we are to seeing multiple approved reprogramming-based therapies, and what most limits the pace of progress today?

Vittorio Sebastiano

I think we are closer than many people realize. The underlying biology has advanced rapidly, and proof-of-concept data continue to accumulate across tissues and disease models. That said, translating reprogramming into approved therapies requires solving challenges that are not purely scientific. The biggest limiting factors today are control, measurement, and trust.

Control refers to achieving precise, predictable outcomes across heterogeneous human tissues. Measurement reflects the need for robust biomarkers that convincingly link reprogramming to durable clinical benefit. Trust encompasses regulatory confidence, physician acceptance, and public perception, all of which depend on a strong safety record. I expect the first approvals to emerge in narrowly defined indications rather than broad “anti-aging” applications.

Once those footholds are established and the risk profile is better understood, progress will likely accelerate. In that sense, the pace of the field is limited less by what reprogramming can do, and more by how carefully we choose to prove it.

Joe Betts-Lacroix

I think we are closer than people would have said five or ten years ago, but still early in terms of approved therapies. It’s worth remembering how young this field really is. Shinya Yamanaka first showed that differentiated cells could be reprogrammed back to a pluripotent state in 2006. The first clear demonstrations of partial reprogramming in living animals, showing rejuvenation without erasing cell identity, came about a decade later, in 2016.

That’s not a long time in medicine. What has moved quickly is the biology. We now know that cellular state can be reset in meaningful ways. What takes time is everything required to turn that scientific insight into clinical therapies that meet the standards needed for use in patients.

The biggest limiter today isn’t whether reprogramming works in principle. It’s manufacturing, safety, delivery, and proving benefit in the clinic, especially for cell therapies. Those are hard problems, and they don’t yield to a single breakthrough experiment.

Another constraint is focus. There is powerful biology behind reprogramming, and it’s tempting to apply it broadly or make big claims early. In practice, progress comes from narrowing the problem, choosing the right indications, and generating clear evidence step by step.

So, I’m optimistic, but not impatient. I expect we’ll see multiple approved reprogramming-based therapies emerge by starting with well-defined diseases, building confidence with regulators and clinicians, and expanding from there. That’s how new therapeutic platforms usually mature, and I don’t think reprogramming will be an exception.

Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson

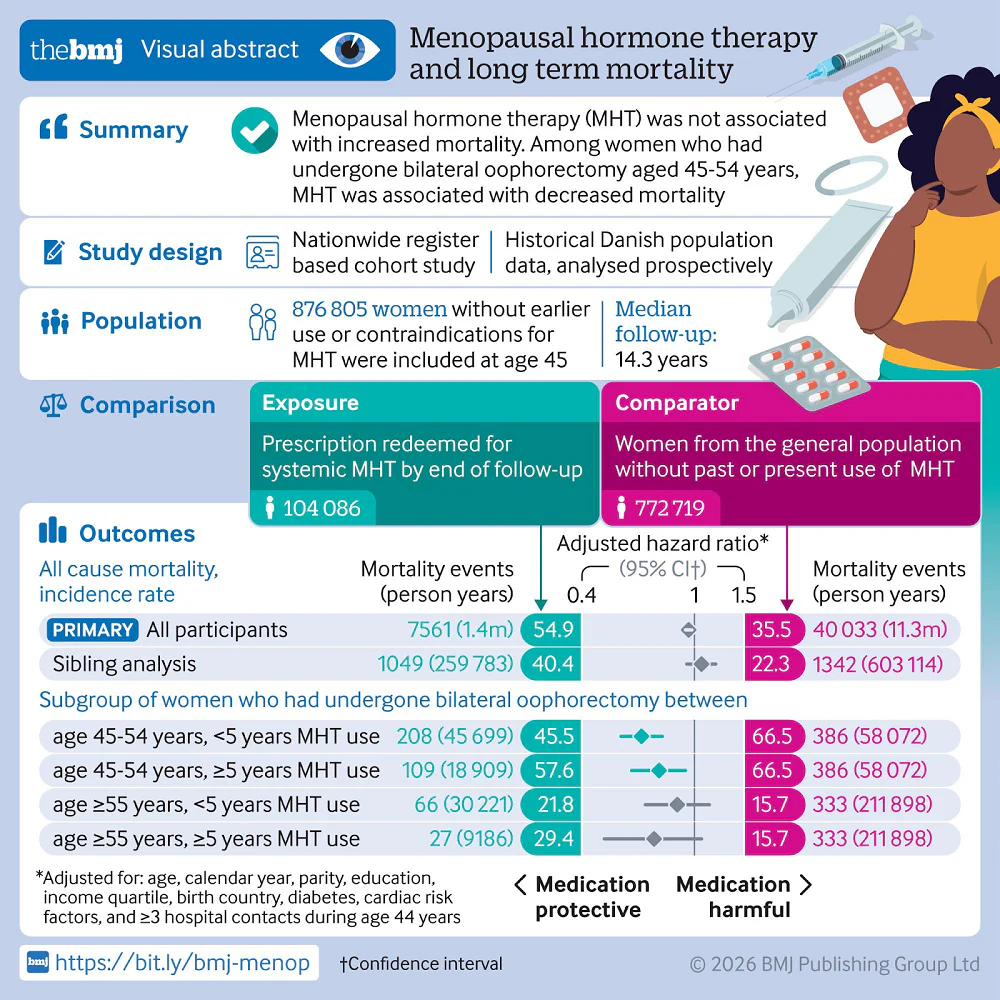

The field has moved from concept to first‑in‑human trials remarkably quickly, and the recent IND clearance for ER‑100 marks an important inflection point for partial epigenetic reprogramming in patients. That said, from my experience in drug development, I would still view broad approval of multiple reprogramming‑based therapies as years away as we need to generate robust safety and efficacy data across several trials.

The main constraints on pace today are less about imagination and more about execution. For example, because this is a first‑in‑class modality, we are working with regulators to build the framework essentially in real time, which requires thoughtful, transparent dialogue but ultimately will benefit the entire field.

Yuri Deigin

I think we’re very close to seeing partial reprogramming therapies tested in humans. The FDA green light for Life Bio’s eye trial was an important milestone for the field, and I’d expect several more programs to enter the clinic over the next 5 years, including our own.

Approvals will take longer — mainly because this is a brand-new modality, and regulators will want careful dose/control, biodistribution, and longer-term safety follow-up, plus clear clinical endpoints. So, my rough expectation is that the first approvals are more likely on a 5–10-year horizon.

As for what limits pace: while I can’t speak for our peers, especially better-funded ones, for us, funding is the biggest limiter. If we didn’t have to be uber-capital efficient, we could parallelize a lot of our activities, as well as tackle more organs and diseases in parallel. And then there’s the universal truth in biotech: biology is hard, and translation always takes longer than you think, even when the underlying science is solid.

What do you expect reprogramming therapies will be able to do for humans in the short and long term?

Vittorio Sebastiano

In the short term, reprogramming therapies will likely function as disease-modifying interventions for specific age-associated conditions, improving tissue function, resilience, and repair where current treatments can only manage symptoms. These early applications will probably be local, targeted, and conservative in scope, but they will demonstrate that restoring youthful cellular states can translate into meaningful clinical benefit.

Over the longer term, I expect reprogramming to reshape how we think about chronic disease and aging itself. Rather than treating degeneration as inevitable, we may be able to periodically restore functional capacity at the cellular and tissue level, extending healthspan rather than simply prolonging life. Importantly, this does not imply immortality or a single universal reset, but a new class of interventions that maintain biological systems within a healthier operating range. If developed responsibly, reprogramming could become a foundational technology, one that complements prevention, regeneration, and precision medicine to fundamentally change how humans experience aging.

Joe Betts-Lacroix

In the short term, I expect reprogramming therapies to look like treatments for specific diseases, not like general anti-aging interventions. The earliest impact will be in conditions where aging is clearly driving loss of function and where resetting cellular state can restore something meaningful, such as immune competence, tissue maintenance, or brain health. What will matter in those first programs is whether they safely produce clear, reproducible clinical benefits.

Over the longer term, the implications are much broader. If we can reliably reset aspects of cellular state without changing cell identity, then aging starts to look more like a modifiable process than an inevitable decline. That doesn’t mean people suddenly stop aging. It means the rate and consequences of aging could be altered in ways that meaningfully extend healthy lifespan.

What matters most to me is that this isn’t just about living longer. The real goal is preserving function. If reprogramming therapies work the way we hope, they could reduce the burden of age-related disease, keep people healthier for longer, and change how we think about the later decades of life. That shift would come gradually, built on therapies that work in real patients.

Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson

In the near term, I believe partial epigenetic reprogramming therapies like ER‑100 have the potential to preserve or restore function in specific tissues that are critically affected by aging, such as retinal ganglion cells in the eye. If we can show that we can safely help retinal cells function more effectively and improve visual outcomes in glaucoma or NAION, that alone would be a major advance for patients who currently have very limited options once damage has occurred.

Longer term, as we learn more about dosing, timing, and tissue‑specific delivery, I expect reprogramming to help address multiple age‑related diseases across organs by intervening at the level of the aging machinery itself. That does not mean “turning back the clock” in a science‑fiction sense; rather, it means extending healthspan by maintaining cellular resilience and function for longer, ideally delaying or mitigating the onset of several age‑driven conditions at once. As a scientist who has seen how devastating neurodegenerative and age‑related diseases can be, that vision of improving quality of life is what motivates me and the team every day.

Yuri Deigin

In the short term, I expect partial reprogramming to produce disease-modifying therapies in specific indications. The first wins will likely be in localized, well-controlled settings — where you can deliver to a defined tissue, dial expression tightly, and measure clear functional endpoints. In that regime, I’d expect partial reprogramming to do things like restore aspects of cellular function and slow or even reverse disease-relevant decline in specific indications.

Longer term, if we really learn to control it safely and repeatedly, reprogramming has the potential to become a platform — something closer to adjusting the body’s “maintenance setpoints” by rewinding the epigenetic operating system across multiple tissues. That’s where you can start talking about systemic rejuvenation, reducing multimorbidity, and delaying multiple age-associated diseases at once. The sky’s the limit but to get there we first need to ensure precise targeting, reliable shutoff, durable benefit, and a safety profile that holds up over many years.

We would like to ask you a small favor. We are a non-profit foundation, and unlike some other organizations, we have no shareholders and no products to sell you. All our news and educational content is free for everyone to read, but it does mean that we rely on the help of people like you. Every contribution, no matter if it’s big or small, supports independent journalism and sustains our future.